Introduction - Radical Parenting

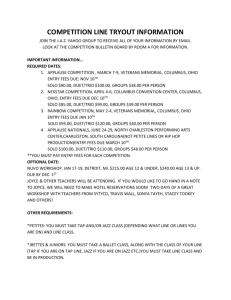

advertisement