Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) V1

advertisement

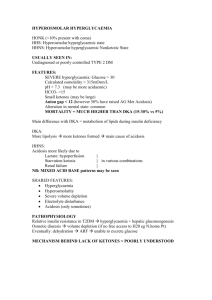

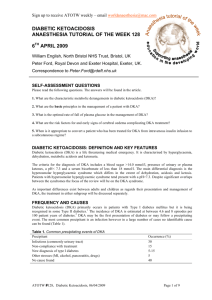

HYPEROSMOLAR HYPERGLYCEMIC STATE Design for African marigold chintz wallpaper, William Morris 1876. “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful”. William Morris, 1882. “Either that wallpaper goes, or I do”. Oscar Wilde, last dying words to his friend Claire de Pratz, October 1900. As Oscar Wilde lay dying in a drab Parisian apartment in October 1900, he was not cheered by his wallpaper! He would have much preferred a more beautiful vision as his last conscious sight in this world. It would have eased his passing no end had he been surrounded by a wallpaper designed by William Morris. Morris was one of the foremost wallpaper designers of the late Nineteenth century. His African marigold chintz design seen above demonstrates his astonishing talent in sketching out the basic pattern, then filling in the color working ever outwards from the center. In the words of Fiona McCarthy, “it can be seen from this design sketch that the apparent spontaneity of pattern is arrived at with enormous technical exactitude”. It is a pity that the interior decorator of Oscar’s apartment had not heeded the wise words of William Morris himself, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful”. Therefore in the sprit of Mr. Morris, it is to be hoped that by the provision of his African marigolds above, these guidelines sketched out with “enormous technical exactitude”, will prove not only useful, but beautiful as well! HYPEROSMOLAR HYPERGLYCEMIC STATE Introduction Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS) The condition was formerly known as HONK Coma (hyperosmolar non-ketotic coma), however the terminology was changed in recognition of the fact that coma is often not a feature of the presentation and in many cases some degree of ketonuria is seen. There is some degree of overlap with DKA however it differs from DKA in its: ● Lesser degrees of ketosis ● Lesser degree of acidosis ● Greater degree of dehydration. Without adequate treatment, mortality is high. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemia is similar to that of DKA: rehydration of the patient and insulin replacement. Pathophysiology ● The quantity of insulin required to inhibit lipolysis in adipose tissue (and hence ketogenesis) is less than the quantity required to promote utilisation of glucose by the peripheral tissues. ● Therefore ketoacidosis does not occur, as there is enough insulin to inhibit lipolysis, but not enough to prevent hyperglycemia. ● There is a slowly developing hyperglycemia and severe dehydration, without the accompanying effects of acidosis, (which is present to a much greater degree in DKA and makes the patient present earlier). Clinical features Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) most commonly occurs in patients with: ● Type II diabetes mellitus ● Middle aged to elderly ● Have some precipitating illness that leads to reduced fluid intake. ● A Precipitating illness, (most commonly infection, ACS). Patients may be known diabetics however HSS may also be a first presentation of diabetes. The illness tends to have a relatively longer prodromal development phase as compared with DKA. Based on the consensus statement published by the American Diabetic Association, diagnostic features of HHS may include the following: 1 1. Plasma glucose level of 33 mmol/ L (600 mg/dL) or greater 2. Effective serum osmolality of 320 mOsm/kg or greater 3. Profound dehydration (up to an average of 9L) 4. Serum pH greater than 7.30 5. Bicarbonate concentration greater than 15 mEq/L 6. Absent to small ketonemia. 7. Neurological impairment: ● Altered conscious state ● Confusion ● Seizures ● Coma Neurological signs tend to correlate with osmolarity rather than acidosis or electrolyte abnormalities. If focal neurological signs are present, then a central neurological lesion must be looked for and excluded. Investigations Blood tests: 1. FBE 2. U&Es / glucose ● Glucose is typically 50-60 mmol / L or higher. ● Corrected Na+ level is high, often 160 mmol / L. Corrected Na+ = measured Na+ and 1/3 (glucose – 10) (This also applies to DKA). There is a marked water deficit in excess of sodium but measured sodium levels are artificially low, due to the marked hyperglycemia, which causes intracellular water to move extracellularly. ● 3. ABGs: ● 4. 2 x (Na+ + K+) + glucose + urea in mmol/L (>320 mosmol / L, if > 350 mosmol / L coma may occur). Blood cultures: ● 6. May show no, or mild acidosis. High osmolarity: ● 5. Variable degree of renal impairment. Consider these as part of search for precipitating illness. Cardiac enzymes. ECG: ● As for any unwell patient. ● Possible precipitating acute coronary syndrome. CXR: ● Possible precipitating acute coronary syndrome. Urine: ● M&C ● FWT CT scan brain: ● This should be strongly considered, as for all patients with an altered conscious state. Management Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemia is along similar lines to that of DKA with rehydration of the patient and insulin replacement, but with some modifications in fluids used and rate of insulin administration.2 1. Immediate attention to any ABC issues. 2. Establish monitoring: ● ECG ● Pulse oximetry. ● IDC For patients who are more severely unwell 3. ● Arterial line ● CVC IV fluid rehydration ● Normal saline may be used as an initial bolus, if there is circulatory collapse. ● Compared with treating DKA, more dilute solutions (such as sodium chloride 0.45%) should be used initially and given slowly. 2 As a general guide rehydrate with solutions according to the corrected Na+ and glucose levels: Corrected Na+ <150 mmol / L >150 mmol /L >150 mmol /L And if glucose >20 mmol /L > 20mmol /L <20 mmol /L Fluid 0.9% saline 0.45% saline 4% D + 1/5 NSaline or 5% Dextrose ● Rehydration is best achieved slowly (to avoid the risk of cerebral edema) over 48 – 72 hours. ● Note that appropriate fluid resuscitation alone can reduce blood glucose by 2-4 mmols/ hr. Rapid falls in sodium, glucose and osmolarity should be avoided: In general: 4. A correction rate of 24-mmol/L per 24 hours in blood glucose levels is acceptable. A correction rate of 8-10 mmol/L per 24 hours in sodium levels is acceptable. Potassium: ● 5. Replace potassium as necessary Insulin: ● Insulin treatment is similar to that for DKA, but usually patients with hyperosmolar hyperglycaemia are more sensitive to insulin and so require lower doses. 2 ● It is not advisable to lower the blood glucose too rapidly in HHS. ● Commence insulin infusion at a slow rate, ie. 0.5 – 2.0 units per hour. 6. Treat any underlying precipitating illnesses or complications. 7. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: ● Venous thromboembolism is a common complication of hyperosmolar states 2 and clexane should be used prophylactically. Disposition ● All patients with HHS must be referred to HDU/ ICU early. ● All patients with HHS must be referred to the Endocrinology Unit early. References 1. Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Murphy MB, et al. Management of hyperglycemic crises in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. Jan 2001; 24(1): 131-53 2. Endocrine Therapeutic Guidelines 4th ed 2009 Dr J. Hayes Reviewed August 2010