Vocabulary Ch 20

advertisement

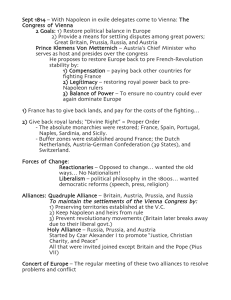

A P European History Vocabulary Chapter 20 The Charles Ferdinand d'Artois, Duke of Berri, the son of Charles, Count of Artois, was assassinated in 1820 and, even though the assassin had acted alone, the Ultraroyalists convinced Louis XVIII that the murder was the results of his government’s cooperation with liberal politicians. And so the king responded with harsh measures. New electoral laws gave wealthy electors two votes. Press censorship was imposed and those suspected of dangerous political activity were arrested. In 1821, the Roman Catholic Church was given control of all secondary education. Thus by the early 1820s, constitutionalism was had been worn away and liberals driven out of politics. The Count of Artois and his followers sensed victory when Louis XVIII died in 1824, but Charles (now Charles X) and his ultraroyalist policies would lead to another French Revolution in 1830. Edmund Burke (1729-1797) was the English political philosopher who was regarded as the father of Conservatism. He held that society was a compact between a people’s ancestors, the present generation, and their descendants yet unborn. Thus Burke believed in the necessity of change, but the kind of change that had to be by consensus or broad agreement. Not surprisingly, Burke condemned radical revolutionaries and the anarchy the resulted from the French Revolution but approved of the American Revolution. Lord Byron, a British poet of the Romantic Movement, went to Greece, fought with the rebels and died of Cholera. George Canning (1770-1827), succeeded Lord Castlereagh (who had committed suicide) and was even less sympathetic to Metternich’s goals. He effectively withdrew Great Britain from continental affairs especially the Congress of Verona. William Cobbett was the editor of the Political Registrar which was a radical newspaper that demanded reform in Parliament and political change such a repeal of the Corn Laws. Frederick William III (r. 1797-1840) the Prussian king allowed reform of the army and land reform during the Napoleonic era. These reforms served Prussia well and helped produce an army which helped to defeat Napoleon. After the Congress of Vienna, Frederick William promised to allow some form of constitutional government. But he stalled and formally reneged on his pledge in 1817. Then, he created a New Council of State which was more efficient – and answerable to the king alone. Ferdinand VII who had his throne taken away by Napoleon, was restored to the Spanish throne in 1814. He pledged to govern Spain by a written constitution but once in power, he ignored his promise, dissolved the Spanish parliament (or Cortés) and ruled as an autocrat. In 1820, army officers, about to be sent to Spain’s colonies in order to suppress Creole rebellions, themselves rebelled against the king. So Ferdinand again pledged to rule by a written constitution. He barely kept his throne and groveled before the revolutionary officers. Kara George was a Serbian patriot leader who led a guerrilla war against the Ottoman Empire from 1804 to 1813 but failed to win Serbian freedom. Lord Liverpool, (Britain’s longest serving P M from 1812 to 1827) became known for his repressive measures to maintain and steer the country through the radicalism and unrest that followed the French Revolution and Age of Napoleon. Liverpool and the Tories sought to protect the interests of the wealthy and landed classes. Louis XVIII was the brother of Louis XVI and became king after the defeat of Napoleon. Louis had become a political realist in his exile and realized that he could not turn back the clock and agreed to become a constitutional monarch but under a constitution, called the Charter of 1814. John Locke (considered the father of classical liberalism) championed legislative government (as opposed to monarchy) because he felt that a legislature embodied the will of the people. Milos Obrenovitch (1780-1860) led the Second Serbian Uprising. By 1817 the Turks defeated his army, but not before he negotiated greater autonomy for most of Serbia with himself as de facto leader. Karl Sand, a student and radical member of a Burschenschaften, assassinated a conservative dramatist August von Kotzebue, who had ridiculed the Burschenschaften in 1819. Sand was tried, publically executed but to many he became a nationalist hero and martyr. Burschenschaften were student associations which were inspired by the reforms of von Hardenberg and vom Stein and laid foundations for a change in loyalty from the old provinces to united German State. In 1817, one of these Burschenschaften celebrated the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig (which drove Napoleon to his first exile on Elba) and the tercentenary of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses. The event was festive and peaceful but made many German rulers uneasy because of its nationalistic undertones. The Carlsbad Decrees of 1819 were laws which Metternich got many German states to pass after the Karl Sand incident. The decrees dissolved the Burschenschaften, cracked down against the liberal press, and seriously restricted academic freedom in many states of the German Confederation. The Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818 saw the four victorious nations (The Quadruple Alliance) agree to remove their troops from France, which had paid its reparations, and to admit France to good standing among the Concert of Europe making the Quadruple Alliance the Quintuple Alliance. The Congress of Troppau took place in 1820 when Metternich met with Prussia and Russia about revolutionary events in Spain and Italy. Austria wanted to intervene but Britain hesitated. The Protocol of Troppau was issued which asserted that stable governments might intervene to restore order in countries undergoing revolutions. But the Congress, especially Alexander I, stopped short of authorizing direct Austrian intervention. The necessary authorization was obtained in 1821 at the Congress of Laibach after which Austrian troops quickly attacked Naples and restored the king and his absolutist government. The Congress of Verona in 1822 was the last meeting of the Quintuple Alliance. Its purpose was to solve the problems of instability in Spain. Great Britain under George Canning balked but Austria, Prussia and Russia agreed to support a French military intervention in Spain which took place in 1823, suppressing the rebellion and restoring Ferdinand to power. The Congress System or Concert of Europe was a byproduct of the Congress of Vienna. At the Congress of Vienna, the victors and soon France had agreed to consult with each other on matters affecting Europe as a whole. This was done through a series of congresses but soon became informal consultations between nations. This new arrangement was known as The Concert of Europe. Its goal was to prevent one nation from taking major international action without working with the other nations – in other words, to preserve the Balance of Power! The Concert continued to function until the third quarter of the century when the unification of Germany and nationalist agitation weakened the congress system. The Cato Street Conspiracy led by a mentally unstable man, Arthur Thistlewood as he and a group of extreme radicals plotted to blow the entire British cabinet. The plot was discovered, the leaders arrested, tried and five executed. Although the plot had little chance of success, it nevertheless helped to discredit the reform movement in Great Britain. The Charter of 1814 provided a constitutional monarchy and bicameral (two house) legislature for France after the fall of Napoleon. The king appointed the upper house, the Chamber of Peers, modeled of the British House of Lords. The lower house or Chamber of Deputies was elected by men of property. The Charter also guaranteed most of the rights enumerated in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 1789. The Roman Catholic Church was declared the official religion but religious toleration was also proclaimed. Perhaps most importantly for the thousands of French people who had profited from the revolution, the Charter promised not to challenge the property rights of the current landowners. The Coercion Acts of 1817 followed disturbances at Spa Fields near London, and temporarily suspended habeas corpus (i.e. government must have proof before and arrest) and extended existing laws against seditious gatherings. Conservatism arose from the American War of Independence and the French Revolution. Conservative comes from the Latin conservare which means to protect or conserve. Conservatives viewed society as an organism that changes (or ought to change) very slowly over the generations. The Corn Law of 1815 (n.b., in Oxford English, corn means all grains) was passed by Parliament in order to maintain high prices for domestic grain by levying import duties on foreign grain. The Eastern Question came about as Europe tried to decide what their response to the Greek War of Independence should be. Simply stated it asked what should European powers do about the Ottoman inability to change and grow technologically? Russia particularly wanted to conquer Constantinople and the Balkan portion of the empire to add to her own empire. Austria also coveted Balkan territory. Britain and France opposed these expansions and were concerned about their commercial interests. The bottom line was that the European powers – even after the Greek Revolution - helped prop up the Ottomans. Nevertheless, the big three (Russia, Britain and France) saw that an independent Greece would be to their advantage. Filiki Eteria was a secret organization that was founded in 1814 to liberate the Greeks from Ottoman rule. The Final Act of 1820 was a law passed by the German Confederation which limited the subjects that could be discussed in constitutional assemblies. The German Confederation was created by the Congress of Vienna in order to prevent the creation of a unified German state or any organizing constitutions. It was the creation of Metternich who was determined that Austria should dominate these small German states and her own minorities. The Greek War of Independence was a successful war of independence waged by the Greek revolutionaries between 1821 and 1832. A series of revolts broke out in 1821and the Greeks won much territory and even built a navy which hindered the Ottomans from sending reinforcements. By 1825 however, the Ottomans, with aid and troops from Muhammad Ali of Egypt, gained the upper hand and retook much of the Greek mainland. But then, after much deliberation, Russia, Great Britain and France, decided that military intervention was in their best interest. They sent naval ships and in 1827 destroyed an Ottoman-Egyptian fleet at the Battle of Navarino. Then French troops landed on the mainland and liberated most of central Greece. In 1827, the three powers signed the Treaty of London which demanded that the Ottoman Turks recognize Greek independence. In 1830, a second Treaty of London declared Greece an independent kingdom and two years later the son of the king of Bavaria, Otto I (r. 1832-1862), was elected king of the Hellenes. Liberalism (derived from the Latin adjective liber meaning free) is the ideology that stresses the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberalism grew out of the Enlightenment and the equality first stressed by early liberals did not include those of the lower classes. Nationalism was the single most powerful ideology of the nineteenth century and can be defined as a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity usually called a nation. Nationalism usually stresses that citizenship in a nation-state should be limited to one ethnic, cultural, religious, or identity group or, if the nation is multinational (as in the United States or Canada), citizenship should be the right of constituent minorities. Nineteenth century conservatives were molded in reaction to the French Revolution and the Age of Napoleon. Politically, nineteenth century conservatism was an alliance between monarchs, landed aristocrats and established churches. In earlier centuries, these groups had competed for power but by 1815, they were allies; sometimes reluctant but allies nonetheless. Nineteenth century conservatives also generally distrusted representative government fearing an attack on their property and influence in society. It was the same with written constitutions unless the conservatives could write the constitution. Nineteenth Century Churches also distrusted liberalism just as they feared and hated Enlightenment ideas because rationalism often (but not always) undermined the teachings of revealed religion. Conservative aristocrats – in spite of Vienna – did not get the message that the new ideologies of popular sovereignty, nationalism and revolution could not be locked away. Led by Metternich and royalists, they believed that they could keep their old privileges and status and suppress their opponents. They could not think “outside the box”, progress or compromise. Conservatism would not die but the day of the aristocrat was about to end. Nineteenth Century Liberals almost always came from the educated, relatively wealthy people who were usually associated with the professions, education, commerce and manufacturing. Their motivation to achieve their goals was spurred on by the fact that they were excluded from the traditional social order because they lacked social (elite) pedigree; especially after the old order (Ancien Regime) prior to 1789 was re-imposed after the Congress of Vienna. They believed in advancement in society based on talent and achievement and demanded more political participation although they did not want full democracy. The core of what they wanted was to extend political rights to their propertied class and, as a result, nineteenth century liberals had no intention of including the peasant or urban working classes into benefits of their goals. Nineteenth Century Liberals sought to create political structures that would limit the arbitrary power of government against citizens, their property and freedoms. They were the children of Adam Smith (the great proponent of Capitalism): the manufacturers of Great Britain, the landed and manufacturing class of France and the growing industrial entrepreneurs of Germany and Italy. Their goal was simple: establish free trade and abolish the economic restraints of Mercantilism along with the regulated economies of monarchies, enlightened or absolutist. They were opposed to established wages and laws protecting the laboring class because they saw them as simply one more commodity that could be bought and sold. In Britain, where the monarchy was limited and most personal liberties had been secured, liberals pushed for more representative government. In France, where the Code Napoleon had secured a modern legal system, liberals called for greater rights since the Code had backed away from the ideals of the Revolution. In Germany and Austria, liberals faced much stronger resistance because the old social divide between the aristocratic, land-owning classes and the middle class commercial and industrial entrepreneurs. As a result, since most German liberals favored a united Germany and looked to either Austria or Prussia to lead the way, they were more tolerant of strong monarchial power than their counterparts in France and Great Britain. German liberals believed that a united Germany would lead to a freer social and political order. The Peterloo Massacre (a sarcastic pun of Wellington’s victory over Napoleon at Waterloo) took place at St. Peter’s Fields in Manchester when an incompetent official ordered militia to deal with a group protest. In the melee that followed many were wounded and eleven people were killed. Although the “massacre’ was the fault of incompetence, the government decided to pass the Six Acts to deal with sedition. Serbian Independence was granted by the Ottoman Empire in 1830. Milos Obrenovitch, now the Serbian hereditary prince kept pressuring the Ottomans to include more Serbian areas into the new Serbia – and he had much success. Serbia faced obstacles however; among them were stabilizing the government; pressuring Austria to free Serbians in the Austrian Empire; and the status of Muslim minorities. In 1856, Serbia came under the protection of the great powers but Russia, Slavic herself, would continue to see herself as Serbia’s special protector, a relationship that would continue until the Great War of 1914. The Six Acts of 1819 were intended to give magistrates more power to restrain radical leaders from agitating the lower classes. The six acts were: 1. The Training Prevention Act, which made any person attending a meeting for the purpose of receiving training or drill in weapons liable to arrest. 2. The Seizure of Arms Act, which gave local magistrates the powers to search any private property for weapons and seize them and arrest the owners. 3. The Misdemeanors Act, which attempted to increase the speed of the administration of justice by reducing the opportunities for bail and allowing for speedier court processing. 4. The Seditious Meetings Prevention Act, which forbade large meetings of fifty or more unless properly authorized by local magistrates. 5. The Blasphemous and Seditious Libels Act, which toughened existing laws for more punitive sentences for the authors of such writings. 6. The Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act, which extended and increased taxes to cover those publications which had escaped duty by publishing opinion and not news. Publishers also were required to post a bond for their behavior Two Treatises of Government was written by John Locke in 1690 and became the foundation of liberal ideology because in it he maintained that in the past people had given up their political rights to rulers in order to promote the common good. He stressed that although people had granted political rights to kings and elites, the people still retained their personal rights of life, liberty and property. Any ruler who violated these rights lost the right to hold his sovereignty and ought to be deposed. Furthermore, rulers logically derived their power or sovereignty from the consent of those whom they governed. If subjects withdrew their consent, they had the right to replace their rulers. Locke not only removed the divine out of the equation of government, he also set up the justification for revolution. Ultraroyalists were the French nobility who did not share Louis XVIII’s spirit of compromise in a constitutional monarchy. They found a champion and rallying point in the king’s younger brother, Charles, the Count of Artois. They sought revenge and within months of Waterloo, they carried out the White Terror (like that which accompanied the Thermidorian Reaction) against former revolutionaries and supporters of Napoleon. The king was helpless to stop the massacres. Similar ultraroyalist sentiment was also found in the House of Deputies. In the elections of 1816, when the Ultraroyalists gained a majority in the House of Deputies, Louis dissolved the chamber. A second election produced a more moderate chamber and several years of give and take followed with the kings making mild accommodation to the liberals.