Equilibrium and inventory adjustment

advertisement

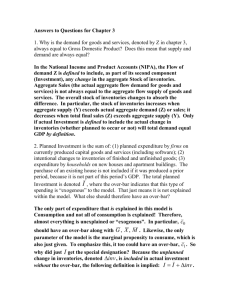

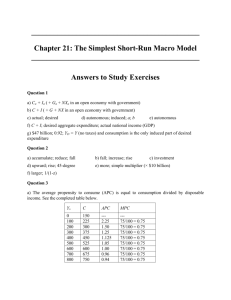

Equilibrium and inventory adjustment. In equilibrium. On the income-expenditure diagram the economy is always on the planned-expenditure line. When the economy is also on the 45-degree line, planned expenditure is equal to national income or real GDP, and is by the circular flow principal equal to actual expenditure and aggregate demand. If the economy is not on the 45-degree line, then planned expenditure is not equal to actual expenditure. Then there is either excess supply or excess demand for the goods produced by businesses. Either the flow of production exceeds aggregate demand, inventories are building up, and firms are about to cut production and lay off workers; or demand exceeds production, inventories are falling, and firms are about to expand production and hire. The circular flow principle states that every expenditure is someone's income, and every piece of income is spent: either spent on consumption, taxed and spent by the government, or saved, loaned out to an individual or firm and then used to finance investment spending or net exports. Whenever aggregate demand is less than national income, some people are planning to save and spend less than they earn. Some firms are producing more goods than they can sell and are losing money. Their behavior will have to change before (or after) they go bankrupt. And when it changes, national income and aggregate demand will match. Inventory adjustment: planned expenditures high. What happens if the economy is not in goods-market equilibrium? Suppose planned expenditures add up to more than national income or real GDP. Then businesses are selling more than they are making. Inventories fall. Some businesses respond to the fall in inventories by boosting prices, trying to earn more profit per good sold. But the bulk of businesses respond to the fall in inventories by expanding production to match demand. They hire more workers. Production, and real GDP, and national income expand. [Figure: income-expenditure diagram starting from falling inventories] Suppose that businesses see inventories fall and boost production to equal last month's planned expenditure. Would such an increase bring the economy back into goods-market equilibrium, with planned expenditure equal to national income and GDP? No. To boost production, firms must hire workers. When they hire workers, they pay more in wages. When they sell more products, they earn more in profits. Thus households' incomes rise. And when incomes rise, total expenditure rises as well. The increase in production and income generates a further expansion in aggregate demand. After production has increased by the initial gap between aggregate demand and national income, the economy is not in equilibrium. Inventories will still be falling. Hiring more workers has increased production, yes. But hiring more workers has also boosted total incomes, and increase planned expenditure. Production will have to expand by a multiple of the initial gap in order to stabilize inventories. [Figure: income-expenditure diagram: multiplier] The process comes to an end--the economy finds itself in equilibrium, with planned expenditure equal to national income and no pressure to expand or contract employment--only when both have risen to the level at which the planned expenditure line crosses the 45-degree income-equalsexpenditure line. Inventory adjustment: planned expenditures low. The same process works in reverse if aggregate demand is below national income: Inventories rise, firms cut production--but the cutback causes demand to fall and inventories to rise further. After production has fallen by the initial gap between planned expenditure and national income, the economy is not in equilibrium. Inventories will still be rising. Firing more workers has decreased production, yes. But firing workers has also reduced total incomes, and decreased planned expenditure. Production will have to fall by a multiple of the initial gap in order to stabilize inventories. [Figure: income-expenditure diagram: multiplier] The process comes to an end--the economy finds itself in equilibrium, with planned expenditure equal to national income and no pressure to expand or contract employment--only when both have fallen to the level at which the planned expenditure line crosses the 45-degree incomeequals-expenditure line. A picky point. The economy can be out of equilibrium, with planned expenditure either higher or lower than national income and GDP, with inventories falling or rising. Yet by definition of the circular flow, economy-wide actual total expenditure--synonymous with aggregate demand--always equals national income or GDP. Isn't this a contradiction? The answer is that statisticians who compile the national income and product accounts (NIPA) define "actual expenditure" in a peculiar way. When production is greater than spending and inventories pile up unexpectedly, the statisticians say the producing company has made an "expenditure," has made an investment in increasing its inventory. Suppose Mammoth Motors produces an extra 100,000 cars, valued at $15,000 each, which it fails to sell. Mammoth thus has the unpleasant surprise of seeing its inventory rise by 100,000 cars: an unexpected inventory increase of $1.5 billion. For Mammoth this is a disaster--it spent a huge sum making things it could not sell. But NIPA statisticians record this as an "expenditure" by Mammoth: an investment in inventories of $1.5 billion. Never mind that Mammoth certainly did not want to make this "investment." The NIPA system is set up to call all changes in every business's inventory an "expenditure" by that business, so that the circular flow principle holds, and (save for accounting definitions and the statistical discrepancy) national income and GDP have to be equal to actual expenditure--planned plus unplanned.