Internal Control - Food Security and Nutrition Network

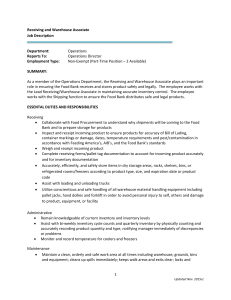

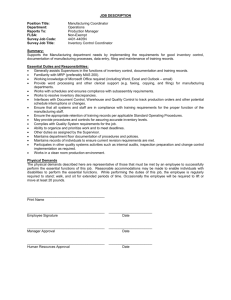

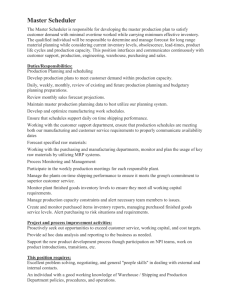

advertisement