Piotrek Walczak

advertisement

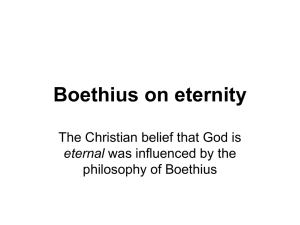

Piotrek Walczak Boethius’ view on omniscience and free will. Boethius was a Roman statesman, philosopher and theologian. By theologians he is well known for his De Trinitate. In the philosophical circles, his work De Consolatione Philosophiae is more valued, especially when the subjects of free-will and necessity are being discussed. This book was written while Boethius was in prison awaiting an execution. It contains a dialogue between the author and a personified “Lady Of Philosophy” that helped him to solve some problems that troubled Boethius, problems that seemed to be theological contradictions. Boethius started with the assumption that philosophical wisdom is a servant to theology and can show logically that divine revelation was non-contradictory. Thanks to philosophical wisdom Boethius could say that human beings have free-will. That is because people have reason and can make intellectual judgments. He divided those judgments into two kinds: speculative and practical ones. The speculative judgments say what really is, that is and they are truth statements. The practical ones are related to what humans do, so they are human action statements. People should use reason to arrive at practical judgments, and each judgment provides means to reach desired end. From those practical judgments, proposed by intellect for achieving a goal, a single one is chosen and it is called an act of free will. It allows the will to be defined as a power of choice. The choice of such kind is completely free and selfdetermined because it is not forced and by an instinctive nature as it is within the rest of the animal kingdom. Animals also make choices, so they have wills. But their wills are not free. Their choices are controlled by their animal nature. “’There is free will,' she answered. 'Nor could there be any reasoning nature without freedom of judgment. For any being that can use its reason by nature, has a power of judgment by which it can without further aid decide each point, and so distinguish between objects to be desired and objects to be shunned. Each therefore seeks what it deems desirable, and flies from what it considers should be shunned. Wherefore all who have reason have also freedom of desiring and refusing in themselves. But I do not lay down that this is equal in all beings (...)”1 Boethius, when considering free will, comes to an obstacle that seems to be irremovable to many theologians, namely; God’s omniscience. If God foreknows everything All quotes are taken form Consolation Of Philosophy, trans: W.V. Cooper, J.M. Dent and Company, London 1902, that can easily be found on the web pages of University Of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center http://etext.lib.virginia.edu 1 == 1 == and cannot be mistaken about what He foreknows, how can human acts be any different from what He foreknows? What God foreknows must of necessity come to pass, otherwise, what God foreknew would be erroneous. Since God cannot be mistaken in His knowledge, what He foreknows must come to pass. That was the center of the problem. If there is necessity and things occur by it, there cannot be any place for free will. “'There seems to me,' I said,' to be such incompatibility between the existence of God's universal foreknowledge and that of any freedom of judgment. For if God foresees all things and cannot in anything be mistaken, that, which His Providence sees will happen, must result. Wherefore if it knows beforehand not only men's deeds but even their designs and wishes, there will be no freedom of judgment For there can neither be any deed done, nor wish formed, except such as the infallible Providence of God has foreseen. For if matters could ever so be turned that they resulted otherwise than was foreseen of Providence, this foreknowledge would cease to be sure. But, rather than knowledge, it is opinion which is uncertain; and that, I deem, is not applicable to God.” But before consideration concerning the difficulty with free-will and God’s foreknowledge Boethius tries to tackle with God’s eternality. He gives his famous definition of eternity: “Eternity, then, is the whole, simultaneous and perfect possession of boundless life”. God has the whole, simultaneous and perfect possession of boundless life, so God is eternal, while the events of human life come into being and then pass away. People have only an instantaneous and momentary now. For us the past has fled away and the future is not yet present. That is totally different than in case of God. He has no past or future. His eternality is ever-present now. All things, all events are ever present to Him as a simultaneous whole. “The common opinion, according to all men living, is that God is eternal. Let us therefore consider what is eternity. For eternity will, I think, make clear to us at the same time the divine nature and knowledge. ' Eternity is the simultaneous and complete possession of infinite life. This will appear more clearly if we compare it with temporal things. All that lives under the conditions of time moves through the present from the past to the future; there is nothing set in time which can at one moment grasp the whole space of its lifetime. It cannot yet comprehend tomorrow; yesterday it has already lost. And in this life of to-day your life is no more than a changing, passing moment.” “What we should rightly call eternal is that which grasps and possesses wholly and simultaneously the fullness of unending life, which lacks naught of the future, and has lost naught of the fleeting past; and such an existence must be ever present in itself to control and aid itself, and also must keep present with itself the infinity of changing time.” Everyone must know according to his own nature. People – who are temporal and spatial – know temporally and spatially. But Got is non-temporal and non-spatial so His knowledge cannot be as human one, it must be non-temporal and non-spatial. God created the time and space. They are objects of His creation and like any other objects they are ever present to God’s omniscience. Human knowledge of the past dims with time and human foresight is == 2 == only speculative while God sees all freshly present. God’s knowledge of all future human events is that all the events are ever present and permanent to Him. In the simplicity of His being everything is seen and known by Him in one sweep of His divine vision. From human point of view it can be said that God foresees something in the future. From the divine perspective God just knows every event and accompanying conditions of time and space. In addition, His knowledge of created beings and their activities is certain and must come to pass. It necessarily must be so because God cannot be mistaken. “Since then all judgment apprehends the subjects of its thought according to its own nature, and God has a condition of ever-present eternity, His knowledge, which passes over every change of time, embracing infinite lengths of past and future, views in its own direct comprehension everything as though it were taking place in the present. If you would weigh the foreknowledge by which God distinguishes all things, you will more rightly hold it to be a knowledge of a never-failing constancy in the present, than a foreknowledge of the future.” That is the moment when Boethius shows his genius. He shows that the knowledge of the event does not cause the event. It was the main reproach of those who deny human freedom. Since God knows everything, all the future events that must necessarily occur, the necessity of these things that are to come eliminates human free will absolutely. But, the knowledge of an event – seen from human perspective – does not cause the event. Then Boethius starts with the famous example with walking man. There may be an observer who sees a person walking. He has the knowledge of that event, but that knowledge does not cause a person to walk. For the observer to know that a person is walking the person must necessarily be walking. Yet, the knowledge and necessity of the person walking do not eliminate the voluntary nature of the person walking. The people who do not see free will must be unable to distinguish God’s foreknowledge and human agency. “Why then do you demand that all things occur by necessity, if divine light rests upon them, while men do not render necessary such things as they can see? Because you can see things of the present, does your sight therefore put upon them any necessity? Surely not. If one may not unworthily compare this present time with the divine, just as you can see things in this your temporal present, so God sees all things in His eternal present. Wherefore this divine foreknowledge does not change the nature or individual qualities of things: it sees things present in its understanding just as they will result some time in the future. It makes no confusion in its distinctions, and with one view of its mind it discerns all that shall come to pass whether of necessity or not. For instance, when you see at the same time a man walking on the earth and the sun rising in the heavens, you see each sight simultaneously, yet you distinguish between them, and decide that one is moving voluntarily, the other of necessity. In like manner the perception of God looks down upon all things without disturbing at all their nature, though they are present to Him but future under the conditions of time. Wherefore this foreknowledge is not opinion but knowledge resting upon truth, since He knows that a future event is, though He knows too that it will not occur of necessity.” == 3 == Now, because God knows everything according to His nature, that is non-temporally. His knowledge embraces every act of the will that voluntary agents freely choose. He knows in an ever-present mode what could be chosen as well as what will be chosen. Every act of human will is known by God and what He knows will necessarily happen. But every act happens according to its own nature, that is acts of free will necessarily will occur but they will occur thanks to the agency of human free will. On the other hand, that which will occur as a result of the laws of physics will also occur necessarily, but these events will necessarily occur through the divine providential laws of nature. “For I shall answer that such a thing will occur of necessity, when it is viewed from the point of divine knowledge; but when it is examined in its own nature, it seems perfectly free and unrestrained. For there are two kinds of necessities; one is simple: for instance, a necessary fact, "all men are mortal"; the other is conditional; for instance, if you know that a man is walking, he must be walking: for what each man knows cannot be otherwise than it is known to be; but the conditional one is by no means followed by this simple and direct necessity; for there is no necessity to compel a voluntary walker to proceed, though it is necessary that, if he walks, he should be proceeding. In the same way, if Providence sees an event in its present, that thing must be, though it has no necessity of its own nature. And God looks in His present upon those future things which come to pass through free will. Therefore if these things be looked at from the point of view of God's insight, they come to pass of necessity under the condition of divine knowledge; if, on the other hand, they are viewed by themselves, they do not lose the perfect freedom of their nature.” When watching from the eternal point of view, God’s knowledge must include the knowledge of all possible worlds. But He decided to actualize one of them, the one which we live in. Simultaneously with bringing this world into being He possesses the knowledge of all volitional events that accompany this particular world He chooses to actualize. Now, watching from the classical point of view, God is the ultimate cause of the universe that has come into the existence. He has preseen every action that each creature would take. He knows what the end of the creation will be. It is not a process for which the outcome is uncertain to Him. Some of the creature’s activities will occur because of God’s divine providence while others will occur through the agency of human free will. Thus, in one of the possible worlds God saw that Judas will freely betray Jesus Christ for thirty pieces of silver. This happens to be the possible world that God chose to actualize. God’s knowledge must have included all aspects of the mental intentions of Judas. Since God’s knowledge is true, Judas must necessarily betray Jesus. Nevertheless, he did it voluntarily. The act of Judas was not the cause of God’s knowledge, rather it was God’s knowledge of the possible world that He chose to bring into existence. Therefore, it is God’s eternal knowledge, what Boethius states, that is the measures of all things. “’But,’ you will say, ‘if it is in my power to change a purpose of mine, I will disregard Providence, since I may change what Providence foresees.’ To which I answer, ‘You can change your purpose, but since the truth of Providence knows in its present that you can do so, and whether you do so, and in what direction you may change it, therefore you cannot escape that divine foreknowledge: just as you == 4 == cannot avoid the glance of a present eye, though you may by your free will turn yourself to all kinds of different actions.’ ‘What?’ you will say, ‘can I by my own action change divine knowledge, so that if I choose now one thing, now another, Providence too will seem to change its knowledge?’ No; divine insight precedes all future things, turning them back and recalling them to the present time of its own peculiar knowledge. It does not change, as you may think, between this and that alternation of foreknowledge. It is constant in preceding and embracing by one glance all your changes. And God does not receive this ever-present grasp of all things and vision of the present at the occurrence of future events, but from His own peculiar directness. Whence also is that difficulty solved which you laid down a little while ago, that it was not worthy to say that our future events were the cause of God's knowledge. For this power of knowledge, ever in the present and embracing all things in its perception, does itself constrain all things, and owes naught to following events from which it has received naught.’” Boethius found the answer to the problem that seemed to be impossible to resolve, that seemed to be a theological contradictory – how to agree God’s omniscience and human free will. He has just divided knowledge into two types. One was the God’s knowledge according to his nature non-temporal and non-spatial, the other was humans knowledge, this time temporal and spatial. This division let him leave God as a perfect being that knows everything and maintain human free will. Then two kinds of necessity follow such a division. The simple one that concerns facts that cannot be denied and the instant one that is related to the facts that are in present. == 5 ==