5. integrated strategy

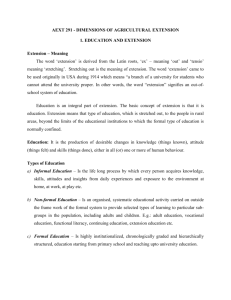

advertisement