10 _main_argument

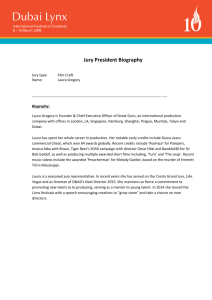

advertisement