Promoting non-violence in schools

advertisement

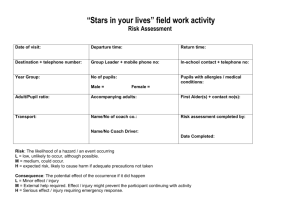

Promoting non-violence in schools: The role of cultural, organizational and managerial factors Ms Dawn Jennifer & Dr Julie Shaughnessy Roehampton University Address for correspondence: Ms Dawn Jennifer Roehampton University Whitelands College Holybourne Avenue London SW15 4JD E-mail: D.Jennifer@roehampton.ac.uk Article accepted by Educational & Child Psychology February 2005 1 Abstract Whilst schools are increasingly being asked to address issues of violence, certain cultural, organizational and managerial factors can obstruct violence prevention reinforcing a culture in which violent attitudes impede the development of a safe learning environment. The focus of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention strategy designed to support schools and young people in promoting non-violence. The longitudinal study (one year) built on the UK-001 CONNECT project funded by the European Union within which Checkpoints was selected for evaluation as part of ongoing work relating to violence in schools. The research design used a test/retest design involving baseline measures and qualitative case study data, including semi-structured interviews, diaries, observations, and documentary evidence. Twelve schools were selected to participate based upon their previous involvement with work on anti-bullying. Three of the final seven study schools experienced a significant decrease in overt bullying and aggressive behaviours. These results are discussed in the light of the qualitative findings which highlighted three organizational models that illustrate the process of a school’s readiness to implement an intervention. The models describe the cultural, organizational and managerial factors that can either inhibit or facilitate the promotion of non-violence. At one end of the spectrum is the school that recognizes the negative consequences of not addressing the issues of bullying and violent behaviour and which is committed to the process of change; at the other is the school that is not yet sensitive to the bullying and violent behaviour experienced by their children and young people, and which experiences difficulty in articulating a clear way forward. Setting the context The World Health Organization (WHO, 1999) suggests that ‘violence affects everyone’. Not only does it undermine the health, learning potential and emotional well-being of young people, staff and community members, but ‘reducing and preventing violence is necessary to help schools achieve their full potential’ (WHO, 1999, p. 3). From the pupil’s perspective, research suggests that a safe learning environment supports pupil participation and interaction with teachers (Turunen, Tossavainen, Jakonen, Salomäki & Vertio, 1999). In turn, positive peer relations in school, operationalized in the school playground, are linked with adjustment to school life generally and with academic success (Coie & Dodge, 1998; Pellegrini & Blatchford, 2002). From the perspective of the staff and organization as a whole, reducing violent behaviour minimizes disruption, supports the authority of the school staff and creates a safe school environment (Hayden & Blaya, 2001). A safe learning environment can decrease tension between staff, decrease workloads, improve the utilization of resources, and decrease disruption to the teaching and learning process (Glover, Gough & Johnson., 2000; Hayden & Blaya, 2001; Neill, 2001). It may also prevent teachers from leaving the profession altogether (Neill, 2001). Children have the right to be educated in a safe environment and every member of the school community is equally entitled to that right. However, in the UK, the results of a large-scale study carried out in Sheffield in 1990, in which over 6,700 pupils participated, suggest that ‘being physically hurt’ is experienced by over one quarter of pupils (Whitney 2 & Smith, 1993). In a longitudinal study carried out by Katz, Buchanan and Bream (2001) in 1996, 1998 and 2000, interview and survey data from 7000 respondents between 13 and 18 years of age suggested that more than half of all respondents had been bullied at some time, with over 10 per cent reporting that they had been bullied severely. In addition, around 20 per cent of girls in the same sample had been violently attacked, with this proportion increasing over the four years of the study. More recently, Glover, Gough and Johnson (2000) reported on the actual nature of physical bullying. In this study, 4,700 pupils aged 11-16 in 25 schools took part in a questionnaire survey which revealed that, within the current school year, 67 per cent of pupils engaged in ‘pushing’, 38 per cent engaged in ‘punching’, 36 per cent engaged in ‘tripping’ and 29 per cent engaged in ‘kicking’. Furthermore, in a report by Gill and Hearnshaw (1997), survey data generated from over 2000 schools revealed that 83 per cent of teachers thought that violence was a serious threat to staff morale and 40 per cent considered that schools were no longer safe places in which to work. Interventions currently in place around the UK specifically relevant to the promotion of non-violence in schools include a wide range of approaches such as, conflict resolution and peer support, health promotion, anger management, and self-auditing tools. One such self-auditing tool, Checkpoints, is a pair of publications aimed at facilitating the promotion of non-violence in schools including Towards a Non-Violent Society: Checkpoints for Schools (Varnava, 2000) and Towards a Non-Violent Society: Checkpoints for Young People (Varnava, 2002). Checkpoints for Schools is a publication with three main functions: to raise awareness, to facilitate institutional selfaudit and to offer guidance. The use of Checkpoints involves a self-audit, the results of which enable a school to identify progress in behaviour management. This is achieved through the completion of a 60-item checklist divided into six sub-lists, known as Checkpoints, covering the main aspects of school life, that is, Home/School/Community (e.g. “Agreed standards of behaviour apply to all members of the school and to visitors”); Values (e.g. “Mutual respect is consistently promoted and expected of everyone”); Organization (e.g. “There is a budget for the implementation of non-violence policies”); Environment (e.g. “Students share in the management of the school environment to reduce the risk of aggressive or violent behaviour”); Curriculum (e.g. “Non-acceptance of violence is prominent in the planning and delivery of the curriculum and the school’s development plan”); and Training (e.g. “[Training might include knowledge about] the different types of violence – physical and non-physical, their causes and consequences”). For each Checkpoint, schools are required to respond to 10 items by ticking either “in place”, “proposed”, or “not in place”. Following completion, results are transferred to a web diagram to create a visual record of the results which, when completed, illustrates a school’s strengths in violence-prevention and highlights areas where further action may be taken. Checkpoints for Young People is aimed at young people experiencing the transition from primary to secondary school; its intention is to offer a second dimension to the process of auditing in that it aims to create a dialogue between young people and adults and provide a framework from within which the voices of young people can be heard. 3 This longitudinal study built on the UK-001 CONNECT project funded by the European Union in which Checkpoints was selected for evaluation as part of ongoing work relating to the promotion of non-violence in schools (see www.ukobservatory.com) Aims and objectives The overall aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of Checkpoints in supporting children, young people and schools in promoting non-violence. More specifically, the key aims were to introduce Checkpoints as a whole school initiative in a cluster of schools; integrate Checkpoints into current initiatives such as the development of Citizenship and Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE), healthy school and teaching and learning policies; evaluate Checkpoints as an intervention strategy - to create new momentum to carry schools further forward in their own practice in the reduction of violence; describe how Checkpoints is successful in effecting change; and evaluate the whole process. Method Design This longitudinal study over one academic year employed a two-group, pre-test/post-test design and a case study approach which included interviews, diaries, observations and documentary evidence. Participants Children and young people from Year 6 and Year 7 in seven case study schools (N = 560), and 5 control schools (N = 674), including one primary, four secondary and one special school. Data collection The participating schools were all volunteers and had been invited to participate because of their existing involvement with other anti-bullying work in the local area. This provided an initial common starting point for the participating schools, which ranged across primary, secondary and special sectors, and represented a range of geographical locations. Case study schools nominated one or two key members of staff who were responsible for the facilitation of the intervention in their school. Nominated facilitators were invited to a launch where the key aims of the study were shared. The case study schools were invited to implement and use Checkpoints for Schools (Varnava, 2000) in an unspecified way in accordance with their current view of bullying and violence in their school. Following administration of the pre-test measures to Year 6 and Year 7 pupils at the beginning of the academic year, the intervention was initially dispatched to study schools only (control schools received the intervention on completion of the study). In-depth qualitative data, including semi-structured interviews with pupils, senior managers and nominated facilitators, facilitator diaries, researcher observations of various aspects of 4 school life (such as, lessons, playtimes, mealtimes, staff meetings, lesson changeovers), and documentary evidence (such as, behaviour management policies and School Development Plans) were collected from the seven case study schools between September 2002 and September 2003 (Yin, 1984). Post-test measures were administered to Year 6 and Year 7 pupils in both case study and control schools at the end of the academic year. Pre- and post-test measures were selected on the basis of considering the impact of the intervention on tangible aggressive behaviour and internal emotional well-being. This paper focuses specifically on The My Life in School Checklist (Arora & Thompson, 1987), a self-completion questionnaire, employed to measure elements of behaviour such as bullying and overtly aggressive behaviours. The secondary version consists of 40-items and the primary version consists of 39-items. The questionnaire consists of a mix of positive items, such as, ‘another pupil was very nice to me’ and negative items, such as, ‘another pupil tried to make me give them money’ describing bullying behaviour, friendly behaviour and aggressive behaviour. Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced the behaviour in the last week either ‘not at all’, ‘only once’ or ‘more than once’. Results Case study data Following data collection, analysis of the case study data was carried out using a Grounded Theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This involved transcribing the interviews, reading the facilitator diaries, and writing up the observation reports; summarizing the transcripts, diaries and reports; and coding and grouping the data into clusters and categories. The initial coding produced key words and phrases from each data source which were clustered into categories. Emergent themes were then identified and together with a selection of key quotations a two-dimensional picture emerged from which the models of school readiness were generated. Analysis of the data identified the schools responses to the intervention. Of the seven study schools, two schools withdrew from the study; one school integrated the intervention; two schools introduced the intervention as an additional initiative; and two schools introduced half the intervention. More specifically School 2 used Checkpoints for Schools with all staff as part of the Behaviour Policy Review and as an extension of the School Development Plan and used Checkpoints for Young People over a series of lessons introducing one Checkpoint at a time; School 3 used Checkpoints for Schools with the Senior Management Team (SMT) as an additional initiative and teaching staff and used Checkpoints for Young People over a series of six/seven lessons addressing one Checkpoint at a time; School 6 used Checkpoints for Schools at a training day for teaching staff as an additional initiative and used Checkpoints for Young People in one lesson addressing all the Checkpoints together; School 4 used Checkpoints for Schools with all staff as an extension of the School Development Plan and did not use Checkpoints for Young People; and 5 School 1 did not distribute or use Checkpoints for Schools with the staff and used Checkpoints for Young People in one/two lessons addressing all the Checkpoints together. Following coding of the case study data as described above eight key themes emerged: philosophy and ethos; leadership and management; home/school/community relationship; behaviour policy and practice; teaching and learning; communication, training and development; and, environment. Following contemplation of the emergent themes and selected quotations, certain cultural, organizational and managerial characteristics emerged that illustrated issues relating to the ability of the organization to engage with change related to behaviour. Three models were generated: the Circular Model, representing a school that is reflexive and responsive, operating from a clearly focused rationale; the Corkscrew Model, reflecting a school that is pragmatic, sometimes reflexive but not always clearly focused; and, the String Model, representing a school that is strategic or autocratic, and experiences difficulty in identifying a clear course of action (see Figure 1 for a summary). FIGURE 1 HERE My Life in School Checklist Statistical analysis was undertaken in SPSS 11.5 and took the form of an analysis of the differences between the means of total pre- and post-test scores derived from the My Life in School Checklist (Arora & Thompson, 1987). Quantitative data was unavailable for School 5 Time 1 and Time 2 and School 7, Time 2 and is, therefore, not reported. The total scores for negative behaviours were totaled to generate composite scores preand post-test for each participant; pro-social behaviours were not incorporated since the absence of such behaviours is conceptually different from the presence of negative behaviours. These scores were used to calculate the mean scores for each school (see Table 1). Table 1: Mean scores and paired samples t-tests for each school for the My Life in School Checklist School Study Primary School 2 School 3 School 4 Study Secondary School 1 N Pre-test mean Post-test mean t value df p 15 20 43 33.73 41.90 36.47 33.93 34.85 32.30 -.117 2.923 2.212 14 19 42 .909 .009** .032* 79 33.53 30.76 4.052 78 .000** 6 School 5 School 6 School 7 Control Primary School 8 School 10 School 11 School 12 Control Secondary School 9 61 37.30 36.59 .575 60 .568 4 10 15 35 31.75 31.20 34.60 29.51 36.25 31.50 28.93 31.34 -1.441 -.132 2.266 -1.320 3 9 14 34 .245 .898 .040* .196 39 33.44 34.56 -1.061 38 .295 * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) Using the mean scores, paired samples t-tests were computed to test the difference between the mean scores at pre-test and post-test for significance. Table 1 presents the results. The results were significant for three out of five study schools, that is, School 1 (t = 4.052; df = 78; p < 0.01), School 3 (t = 2.923; df = 19; p < 0.01) and School 4 (t = 2.212; df = 42; p < 0.05). In other words, the total negative behaviours experienced was significantly lower post-test compared with pre-test. School 6 experienced a decrease in negative behaviours between pre- and post-test but this was not significant. School 2 experienced an increase in negative behaviours but this was not significant. Results were significant for one of the control schools, that is, School 11 (t = 2.266; df = 14; p < 0.05). In other words, the total negative behaviours experienced was significantly lower at posttest compared with pre-test. For the remaining control schools, that is, Schools 8, 9, 10 and 12, the increase in negative behaviours was insignificant. Discussion In consideration of the results, the researchers would like to highlight that whilst the study was intentionally designed to be non-prescriptive, that is, study schools were invited to implement the intervention in an unspecified way and in accordance with their own perspective of bullying and violence in their school, it is possible that the My Life in School Checklist (Arora & Thompson, 1987) was not a suitable measure for measuring the efficacy of Checkpoints as only one of the schools actually integrated the intervention as a whole-school initiative, and not all of the schools implemented all of the intervention. This observation is not meant as a criticism of the participating schools, rather an acknowledgement that the nature of the school as an organization is such that, in view of the findings, the variety of ways of implementing the intervention may not be conducive to the administration of such tests. Given the findings, in research such as this which employed a pre-test/post-test design, it could be argued that the conditions of implementation ought to have been controlled by the research team. That said, the results suggest that three out of the five study schools experienced a significant decrease in overt bullying and aggressive behaviours, such as hitting, tripping 7 or shouting. Taking the quantitative and qualitative results together, what the findings suggest is that in School 1 this may have been due to Checkpoints for Young People being used with Year 7 over one/two lessons; in School 3 this may have been due to Checkpoints for Schools being introduced as an additional initiative with Checkpoints for Young People being used with Year 6 over a series of lessons taking one Checkpoint at a time; and, in School 4 this may have been due to Checkpoints for Schools being introduced as an extension of the School Development Plan. An alternative explanation, according to Arora and Thompson (1987), is that there are seasonal variations in levels of bullying, with rates often higher in the Autumn term, when the pre-test measures were administered, and lower in the Summer Term, when the post-test measures were administered, although, data from the control schools does not support this. Bearing in mind this alternative explanation, it might have been preferable to administer the measures at the same time in the academic year, although this would have presented problems with the Year 6 cohort who would have made the transition from primary to secondary school by the time of the post-test administration. Future research might consider recruiting Year 5 and Year 7 pupils for the study with post-intervention measures being carried out in Year 6 and 8 respectively. Furthermore, the results may have been more conclusive had the study run for two years instead of one; Smith, Ananiadou and Cowie (2003) suggest that programme length is an important variable with longer interventions being more successful. With regard to the control schools, levels of overt bullying and aggressive behaviours had significantly decreased for one school. This decrease could be explained in terms of the seasonal variations outlined above, although these results were not common to all the control schools; alternatively, it could be that this control school was involved in its own activities or initiatives that had an impact on the levels of bullying and aggressive behaviours. With hindsight, it would have been helpful to conduct follow up interviews with the control schools at the end of the study to ascertain what activities and initiatives they had been engaged in during the academic year, which may have helped explain the findings. Despite the design and methodological limitations outlined above what the results from the case study analyses suggest is that the process of implementing and, in some cases, integrating Checkpoints acts as a tool to raise awareness about auditing and selfevaluation. For example, one headteacher said ‘it provided the focus for the work on non-violence. It was also useful to refer back to the documentation for self-evaluation throughout the year’. However, whilst the qualitative data suggests that Checkpoints achieves two out of three of its main functions, raising awareness and facilitating institutional self-audit, it failed to achieve the third in terms of offering guidance. Another headteacher said ‘we moved to doing our own development of behaviour as we felt there was no back up once the audit was done’. Thus, notwithstanding the nonprescriptive nature of Checkpoints, it could be argued that the level of support that individual schools required for implementation was not adequate. However, an evaluation of an anti-bullying intervention in Flanders suggests that extra support from 8 researchers had no additional effect (Stevens, de Bourdeaudhuij & van Oost, 2000). Indeed, Smith et al., (2003) suggest that perhaps what is important is not the level of support provided by the research team but how much time and effort schools themselves invest in the intervention. Our results concur with this suggestion in terms of a school’s readiness to implement an intervention, and offer a unique insight into the process of addressing change in terms of cultural, organizational and managerial factors. The results suggested that some schools were more ready to embrace organizational change than others, and thus more ready to implement the intervention. This process can be understood in terms of the three models of readiness (see Figure 1): The Circular Model reflects an organization that is self-aware and responsive and operates from a clearly focused rationale. The school is able to prioritize its course of action and is aware of the need for constant review and evaluation of practice. The culture in the school could be characterized as democratic with a focus on children’s participation in decision making. The school recognizes the negative consequences of not addressing the issues of bullying and violence and is committed to the process of change. The school has an internal locus of control. A school operating from this model of readiness is likely to implement both Checkpoints for Schools (Varnava, 2000) and Checkpoints for Young People (Varnava, 2002) as an extension of the School Development Plan. The Corkscrew Model reflects an organizational culture that fluctuates. The school is sometimes able to identify action through self-reflection but the action is not always clearly focused. The culture in the school could be characterized as pragmatic with some emphasis on children’s participation. Whilst the school acknowledges the existence of bullying and violence, takes ownership of the problem, and identifies some of the negative aspects of its presence, it is ambivalent about committing to the process of change. The school has a locus of control that fluctuates between external and internal input. A school operating from this model of readiness is likely to either feel complacent about the issue of violence or to feel ambivalent about implementing Checkpoints. The String Model reflects a fragile organizational culture. The school has limited selfevaluation and experiences difficulty in identifying a clear course of action. The culture in the school could be characterized as strategic with little emphasis placed on children’s participation. The school is not yet sensitive to the bullying and violence experienced by their children and young people; however, others may be aware of a problem, for example, parents or the wider community. The school has an external locus of control. A school operating from this model of readiness is unlikely to have much success with implementing Checkpoints. A school’s readiness to change, therefore, will be dependent upon the extent to which the key elements defined in the three models will support the introduction of an intervention and whether children, young people and staff are empowered to participate meaningfully 9 in its development. This concurs with the work of other researchers (for example, Dusenbury, Falco, Lake, Brannigan & Bosworth, 1997; Roffey, 2000; Sammons, Hillman & Mortimore, 1995). In an educational climate in which schools are increasingly being asked to address issues of bullying and violence, a school’s understanding of its readiness to implement an intervention is an important starting point for the successful promotion of non-violence. Without this understanding, schools will have little success in addressing the issue of change. In analyzing the process of implementing and, in some cases integrating the intervention, it has been possible to not only define the process, but also to suggest a model of readiness which emphasizes key elements of cultural, organizational and managerial factors that may either impede or facilitate change. The importance of school ethos in promoting positive behaviour and effective learning has long been acknowledged and defining and examining a school’s ethos is therefore vital for understanding how violence can be prevented. In an educational climate in which schools are inundated with initiatives, understanding the factors within an organization which influence learning and using a tool to determine readiness to change are the crucial first steps for the promotion of non-violence. Only schools that recognize the negative consequences of not addressing the issues of bullying and violent behaviour, and who are committed to the process of change, will be able to enhance the development of a safe environment for learning and teaching, thus providing a positive schooling experience for children and young people. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those children and young people, staff, schools and the Local Education Authority who took part in this research and who gave generously of their time. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewer for commenting on the original draft of this paper, and Tony Daly for his comments on the final version. References Arora, C. M. J. & Thompson, D. A. (1987). My Life in School Checklist cited in S. Sharp (1999) Bullying Behaviour in Schools. Windsor: NFER WILSON. Coie, J. D. & Dodge, K. A. (1998). Aggression and anti-social behaviour. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.) Handbook of Child Psychology, 3, 779-862). New York: Wiley. Dusenbury, L., Falco, M., Lake, A., Brannigan, R. & Bosworth, K. (1997). Nine critical elements of promising violence prevention programs. Journal of School Health, 67(10), 409-414. Gill, M. & Hearnshaw, S. (1997). Personal Safety and Violence in Schools. DfEE Research Report 21. London: HMSO. Glaser, B. & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago: Aldine. 10 Glover, D., Gough, G. & Johnson, M. (2000). Bullying in 25 secondary schools: incidence, impact and intervention. Educational Research, 42(2), 141-156. Goodman, R. (1999). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581-586. Hayden, C. & Blaya, C. (2001). Violent and aggressive behaviour in English schools. In E. Debarbieux & C. Blaya (Eds.) Violence In Schools, (pp. 47-73). Issy-lesMoulineaux: ESF. Katz, A., Buchanan, A. & Bream, V. (2001). Bullying in Britain: Testimonies from Teenagers. London: Young Voice. Neill, S. R. St J. (2001). Unacceptable Pupil Behaviour: A Survey Analysed for the National Union of Teachers. University of Warwick, Institute of Education. Pellegrini, A. D. & Blatchford, P. (2002). Time for a break. The Psychologist, 15(2), 60-62. Roffey, S. (2000). Addressing bullying in schools: Organizational factors from policy to practice. Educational and Child Psychology, 17(1), 6-19. Sammons, P., Hillman, J. & Mortimore, P. (1995). Key Characteristics of Effective Schools. London: Institute of Education/Office for Standards in Education. Smith, P.K., Ananiadou, K. & Cowie, H. (2003). Interventions to reduce school bullying. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(9), 591-599. Stevens, V., de Bourdeaudhuij, I. & van Oost, P. (2000). Bulling in Flemish schools: an evaluation of anti-bullying intervention in primary and secondary schools. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 195-210. Turunen, H., Tossavainen, K., Jakonen, S., Salomäki, U. & Vertio, H. (1999). Initial results from the European network of health promoting schools program on development of health education in Finland. Journal of School Health, 69, 387-391. Varnava, G. (2000). Towards a Non-Violent Society: Checkpoints for Schools. London: National Children’s Bureau. Varnava, G. (2002). Towards a Non-Violent Society: Checkpoints for Young People. London: National Children’s Bureau. Whitney, I. & Smith, P. K. (1993). A survey of the nature and extent of bully/victim problems in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educational Research, 35, 3-25. World Health Organization (1999). Violence Prevention: An Important Element of a Health-Promoting School. Geneva: WHO. Yin, R.K. (1984). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Sage. 11 Figure 1: Readiness models 12