Introductions - Colby College Wiki

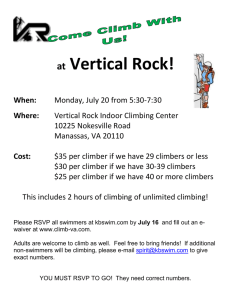

advertisement