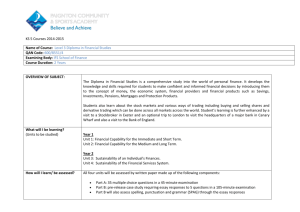

POSTGRADUATE DIPLOMA IN MARKETING AND MANAGEMENT

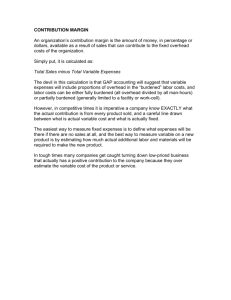

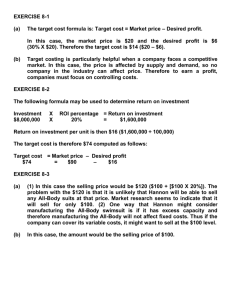

advertisement