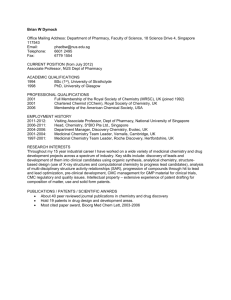

Professor Robin Zavod, PhD, 1992, University of Kansas

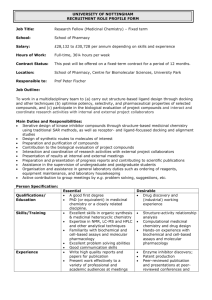

advertisement