Graph 2 - Retail Food Price Index1 / Wholesale Food Price Index2

advertisement

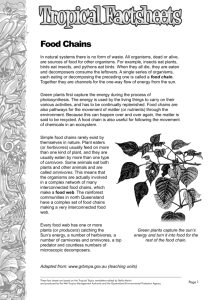

1 Distribution and the price of food: Competition and the Hunger Millennium Development Goal1 Global commodity chains do not consist merely of flows of materials across national boundaries. They consist of networks whose key decision-makers influence the outputs of the chain and its composition. (Dolan and Humphrey,2001) A straightforward relationship between food distribution and prices and development could be stated as follows. Food and drink expenditure takes an important share in poor people’s income. In Brazil, for example, food responds for about 17% of families’ total expenditure, while for low-income group, this participation increases to 32% (Table 1). A decline of food prices raises real wages, without further impact in general production costs. A sustainable raise in real wages foster the market for industrial goods and enables families to invest in education. These effects can build blocks of a virtuous circle in which effective demand and factor’s productivity grow jointly. If the ubiquitous wave of mergers and acquisitions in retailing and food processing sectors provoke a rise in food prices, development could be hampered and poverty deepened. Furthermore, agricultural prices could be negatively affected by the rise of buyer’s power, reinforcing the negative impacts on development of rural areas, and poverty. The natural conclusion that arises from the former reasoning is that competition authorities should assume a presumption against allowing mergers among food retailers to take place. Though extremely appealing this reasoning may not be confirmed in developing countries, and the Brazilian experience shows a very different scenario. Retailing concentration, competition policy and Food Prices – the Brazilian experience During the 90’s a strong wave of mergers and acquisition took place in the Brazilian retailing and food processing sectors. From 1994 to 2005 the five largest supermarket chains almost doubled their market-share (considering the retailing of food and non-food products), while the ten largest food processors controlled almost one third of industrialized food sales. In Chile and Argentina, the increase in market share of the big supermarket chains is similar to the Brazilian experience as shown by Table 2. The ideas and opinions presented on this paper are personal and do not reflect any CADE’s or official opinions/position. 1 2 Many operations were submitted to the Brazilian Competition System and the concern of the authorities with the rapid concentration in the supermarket sector was clear. In the majority of the cases, the Secretary of Economic Monitoring and/or the Secretary of Economic Defense suggested the approval with restrictions, and determined that several supermarket stores were sold2. The diagnoses were mainly based on the presumption of high entry barriers3 and insufficient rivalry. However checking what really happened to the post-merger situation, it is easy to conclude that there has been a systematic overvaluation of the barriers to entry. Even before the final decision was made, several entries had already occurred or the market-share of the merged firms declined, due to rivalry among the remaining firms4. That is, despite the high concentration in supermarkets sector a better understanding of the pattern of competition is required. During nineties, real retail food prices slumped 50% in average, and from 2000 to 2005 the decline continued to happen, though in a lower magnitude. (Graph 1). The impact on real income of the low-income population was expressive and had positive distribution effects. The first consequence was a strong increase in food demand, without reversion of the price decreasing trend. Meanwhile, a strong merger wave was in progress. Empirical studies using non-parametric tests (Almeida, 2003) rejected the hypothesis that the increase in the degree of concentration in the Brazilian food retailing is correlated to the increase of food prices to the consumer. Changes in the degree of concentration among different Brazilian regions in food retailing were not significant to explain the variations in the food prices to the consumer. Furthermore, retail food prices decreased more than wholesale food prices (Graph 2). In Chile, according Morgan Stanley (2004), “… increased competition in Chile’s supermarket sector — particularly among non-perishable food products — has helped push food prices down […]”.5 Wal-Mart’s motto, “always low prices”, expresses the new role of retail competition. That is, despite the high market share of the 5 largest supermarket chains, competition is responsible for lower food prices. As a matter of fact, former monetary stabilization and prices liberalization increased competition and are in the roots of the Brazilian food retail restructuring. The growth of the leading companies was achieved by costs rationalization, green investments but mainly through M&A of large and medium supermarket chains. The result of the process as a whole, was the exploration of scale and scope economies, increasing productivity and efficiency, not only within the stores but also in the procurement systems 2 Some of these cases are still under analysis Based on the calculation of Minimum Efficient Scale, the markets were characterized as highly concentrated, by the non-existence of effective competitors and small opportunities of sales, what could make the entry more difficult. Therefore, it was recommended the sale of specific stores 4 OECD DAF/COMP/WD(2005)70, EM 07-Oct-2005 - Roundtable On Barriers To Enter,19 October 2005,Contribution From Brazil – Cade 5 http://www.morganstanley.com/GEFdata/digests/20040121-wed.html 3 3 adopted. Because of competitive advantages of the big retail, the only alternative for medium and small businesses would be to sell their companies and leave the market or to find ways to compete with lower prices and/or differentiated services. Therefore, movement of acquisitions was not restricted to the largest firms: acquisitions occured among the smaller chains, which in turn have been incorporating independent units. A more careful look at the food retailing evolution in Brazil, confirm the easy of entry. Despite the increase of the degree of concentration in the segment of supermarket chains, Farina & Nunes (2003) noted a discrete trend of deconcentration in food retail at a national level. This trend is associated to the expansion of the independent supermarkets (in number of establishments and market share) and of traditional retail (only in number of establishments), as shown in Table 2. The regional reality, however, shows important distinctions. The more densely populated metropolitan regions with higher income presented greater advances of supermarket chains. Big retailers were responsible for more than 70% of food sales in the large Metropolitan Regions of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In the other areas, this number was between 20% and 50%. The similar distribution in the large metropolitan areas suggests that the urban densification favors the presence of supermarket chains, whose performance would depend on larger consumer markets. In all regions but two, the relative weight of the chains in food sales was reduced, due to the expansion of independent supermarkets. In the large metropolitan regions the share of this form of retail was stable. That is, the empirical evidence does not support the theory of the disappearance of small retail caused by the expansion of the supposedly more efficient large supermarket chains. At the same time, the food price behavior, and a more extensive variety of stores and services show that the urban consumers have benefited from these changes. Big retailers, competition on quality and farmer’s income Despite the competition environment in the food markets, another problem could arise if the decline in food prices in the urban areas reflects an impoverishment of the rural area. That is, if the strongest buyer power of big retailers could impose most part of the lower price burden on the agriculture producer. For sure, the reduction of costs with the acquisition of merchandise obtained principally from price negotiation, conditions of payment, and added services from suppliers partially explain .the improvement in the operational results of food retail. Therefore, the sustainability of high urban real wages could be threatened by accelerated depreciation of physical and human capital allocated in agricultural sector. Too low prices in present could mean too high prices in future, since present standard of life 4 would result from the depletion of a stock of physical and human capital previously accumulated in agricultural sector and food industry6. Once more, the Brazilian experience does not support this hypothesis. During the nineties, agricultural prices grew more than food prices, as shown in Graph 3, so the real slump of food prices happened without looses in the rural income. Besides price competition, the modern retail strategy has spurred competition based on products quality and convenience of stores. Large supermarket chains, most of them multinational enterprises, introduced private quality and safety standards, in order to compete on product differentiation. The consequence to suppliers is as challenging as the power on price negotiations. Competition on food safety and quality is based on standards. In less developed countries (LDC) public quality standards are often absent or weakly enforced. A probable outcome from differentiation competition in LDC is the market segmentation in two groups: one of them embraces high price and quality products and consumers willing to pay; the other group contains low income and weakly concerned in quality consumers. A market failure arises when products have hidden attributes and there is no or weakly enforced public standards. Large informal production characterized by tax evasion and no compliance to public basic standards, reinforces the food market segmentation based on quality attributes. According Dolan and Humphrey (2001), large retailers in Europe play a decisive role in structuring the production and processing of fresh vegetables exported from Africa. “The requirements they specify for cost, quality, delivery, product variety, innovation, food safety and quality systems help to determine what types of producers and processors are able to gain access to the fresh vegetables chain and the activities they must carry out”. Multinational retailers and food market enlargement Foreign direct investment (FDI) is one of the leading forces of the M&A wave in retail. Multinational retailers used to build supply chains connecting farmers and food industries of the regions where they are settled. Carrefour, the 2nd retailer in the world, started investing offshore in 1973, in Spain. Two years later, Carrefour opened its first hypermarket in Brazil. In 1982, the chain reached Argentina, and in 1989, Taiwan. The internationalization of Carrefour chain was intensified in the ‘90s. Nowadays the group is present in 29 countries with 6,546 stores. Its strategy consists of building group market share in each country in which it does business by expanding the type of retailing best suited to the local market and by taking advantage of the way their formats complement one another. 6 In order to prevent big retailers abuse of upstream market power, retailers of Argentina adopted voluntarily a conduct code that banished practices such as price squeeze and unjustified price discrimination. Self-regulation tends to reduce transaction costs in supply chain, but it is not enough to prevent damages when incentives and monitoring costs are high. 5 Among Carrefour’s strategic priorities are the effort “to strengthen the partnerships with the local companies in all countries and promote fair and long-term relations with suppliers” and the adaptation to local demands. Wal-Mart, the world’s first retailer, extended its activities to 11 countries: United States, Mexico, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Puerto Rico, Germany, China, South Korea, United Kingdom and Japan. Raikes et.al (2000, 393) stated that demand-driven chains may give more opportunities for advantageous higher value added participation from developing countries. According the authors, even subordinate participation in global chains can provide indirect access to markets at lower costs than faced by individual small producers Welfare benefits from standards dissemination are twofold. Standardized products benefit consumers directly. Farmers are also benefited from the knowledge transfer needed to reach standards and from the enlargement of market opportunities for their standardized products. Sometimes multinational supermarket chains adopt a global supply strategy that matches with local farmers capabilities. The highest barrier to reach global markets is the missing knowledge concerning the attributes of demanded products and the supply channels, and multinational supermarket chains have helped farmers to overcome knowledge barriers. In 1999, four largest supermarket chains in UK offered asparagus from Zimbabwe, Thailand, Peru, Guatemala and Spain, corn from Thailand, Kenya, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Guatemala, and fine beans from Kenya, Gambia and Zambia (Dolan and Humphrey,2001). Consumers in developed region are benefited from a wider space of choice and opportunity of taste exotic food. These consumers are buying far more tropical products, many items for the first time. Reardon et al. (2001) give an example: the recent appearance of mangoes and chirimoyas (custard apples) from Latin America on supermarket shelves in the U.S. Midwest. As UNCTAD (2005) pointed out, “there is a growing trend towards harmonizing private sector standards among international supermarket chains, making conformity with those standards a requirement for market access”. The other side of the coin is the effect of high compliance costs and potential or actual trade losses, due to competition with more gifted producers. Intra-firm exports of supermarket chains tend to grow quickly, as theirs supply chains include new regions where investments are settled. Tariff reductions and improvements in transport systems have globalized supermarket supply chains. For example, the cost of sea freight fell almost 70% between the early 1980s and the mid 1990s. (Brown, 2005) Market access created by intra-firm food trade was not enough however to make LDC exports grow faster than global food trade. Graph 4 shows that developed 6 countries and the rest of the world have both equilibrated food trade balances . Farmers connected to global agri-food networks experiment income raises, but this seems to be a marginal phenomenon unacapable to change the present international food trade pattern. Conclusion Despite the growth of leading food retailers, and also food processors, food relative prices have declined in several developing economies. Furthermore, a growing variety of products and services have been provided to urban consumers. This result brings positive effects to development process as contributes to increase real wages without impact the production costs. Though the Brazilian experience does not support the widespread view medium and small retail is disappearing, there has been a strong competition pressure on them. However, the positive efficiency effects that have resulted of the more competitive environment for urban consumers, especially for lower-income population, does not recommend any intervention to protect the smaller retailers, or even food processors. The negative impact on the rural area and smaller businesses upstream that has raised major concerns on Governments deserves attention, but also does not recommend any anticompetitive intervention, such as price regulation. Most important are the changes related to public and private standards, set by big retailers and food processors. There will not be one international standard, but a number of standards that will be met by different suppliers. Instead of an inevitable and endless concentration process, there seems to have a tendency of continuous differentiation among consumers, retailers, processors and farmers in a much more complex system of relations than is currently described. If this scenario is correct, it is worthless to try to stop the recent tendency of adopting private standards. On the contrary, in order to improve the capacity of small farmers and small businesses to benefit from these trends, a constant provision of information and proximity to the most dynamic markets is needed. For the small, information is costly and sometimes impossible to obtain. A close relationship between governments and small business associations with international organizations could fulfill this gap. Governments and International Organizations are not able of avoiding exclusion in the competition process. Most of all, it is not desirable. Consumers have benefit from the recent developments in the food system. Consumers of developing countries also benefit from lower food prices that are provided by big retailers. They cannot afford to pay higher food prices in order to preserve small retailers and food processors or even small farmers. What is desirable is that the small have the opportunity to be efficient and respond to market trends (from Farina et all. Report to OECD, 2005). References Almeida, S. F.de. (2003). Impactos da Concentração do Setor de Varejo de Alimentos sobre o Consumidor. Thesis - Departament of Economics. School of Economics, Business and Accounting. São Paulo University - FEA/USP, São Paulo. 7 Brown, O. (2005) Supermarket Buying Power, Global Commodity Chains and Smallholder Farmers in the Developing World. UNDP - Human Development Report 2005. Occasional Paper. CEPAL (2001) Foreign investment in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2001 http://www.cepal.org/publicaciones/DesarrolloProductivo/8/LCG2178PI/LCG2178_ARGE NTINA.pdf Dolan C., Humphrey, J. (2001) Governance and Trade in Fresh Vegetables: The Impact of UK Supermarkets on the African Horticulture Industry. Journal of Development Studies 37(2) Journal of Development Studies 37(2): 147-176. Supermarkets and their Impacts on the Agrifood System of Brazil: the competition among retailers , Agribusiness: an International Journal, vol 21(2) 133-148, 2005 Wiley Publishers, ISSN 0742-4477 Farina, E.M.M.Q., Nunes, R. & Monteiro, G.F, Revising the paper The Rapid Rise of Supermarkets and the Use of Private Standards in their Food Product Procurement Systems in Developing Countries, OECD report, 2005 Farina, E.M.Q. and Nunes, R. (2003) A Evolução do Sistema Agroalimentar no Brasil e a Redução de Preços para o Consumidor: os Efeitos da Atuação dos Grandes Compradores. Texto Para Discussão, Brasília, v. 970, p. 1-68, 2003. IBGE, 2003. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares – POF. www.ibge.gov.br Raikes Ph., M.F. Jensen, S. Ponte: Global Commodity Chain Analysis and the French filière Approach: comparison and critique. in: Economy and Society, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 390-417, August 2000 Reardon et al. (2001) Global Change in Agrifood Grades and Standards: Agribusiness Strategic Responses in Developing Countries. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 2(3/4): 421–435 UNCTAD (2005) Developing Countrien in International Trade 2005 http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/ditctab20051ch2_en.pdf 8 Table 1 - Brazilian households food expenditures per month - 2003 Income Range R$ Till 400 More than 400 to 600 More than 600 to 1000 More than 1000 to 1200 More than 1200 to 1600 More than 1600 to 2000 More than 2000 to 3000 More than 3000 to 4000 More than 4000 to 6000 More than 6000 Total Households n 7.949.351 6.747.421 10.181.484 3.528.908 5.086.643 3.349.073 4.571.410 2.416.195 2.236.892 2.467.262 48.534.638 % 16,4 13,9 21,0 7,3 10,5 6,9 9,4 5,0 4,6 5,1 100,0 Food Expenditure R$ 148,59 195,85 234,26 282,12 312,33 359,76 397,94 474,54 523,77 788,70 304,12 Total Expenditure R$ 454,70 658,18 920,69 1.215,33 1.494,43 1.914,35 2.450,03 3.270,20 4.445,42 8.721,91 1.778,03 Food / Total % 32,7 29,8 25,4 23,2 20,9 18,8 16,2 14,5 11,8 9,0 17,1 Source: IBGE, 2003. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares - POF (Household Budget Survey) Table 2 – Supermarkets in Latin América - Concentration and Multinationalization 2002 Brazil Share of top 5 Share of foreign Share of foreign chains in multinationals-full ownership multinationals in top 5 supermarket sales* or joint venture) in chains´ sales supermarket sales 47% 64% 84% Argentina 76% 43% 91% Chile 55% 10% 18% * Sales include food and non-food products and durable goods as well. 94 19 01 94 19 06 94 19 11 95 19 04 95 19 09 96 19 02 96 19 07 96 19 12 97 19 05 97 19 10 98 19 03 98 19 08 99 19 01 99 19 06 99 20 11 00 20 04 00 20 09 01 20 02 01 20 07 01 20 12 02 20 05 02 20 10 03 20 03 03 20 08 04 20 01 04 20 06 04 20 11 05 20 04 05 09 19 90 19 01 90 19 07 91 19 01 91 19 07 92 19 01 92 19 07 93 19 01 93 19 07 94 19 01 94 19 07 95 19 01 95 19 07 96 19 01 96 19 07 97 19 01 97 19 07 98 19 01 98 19 07 99 19 01 99 20 07 00 20 01 00 20 07 01 20 01 01 20 07 02 20 01 02 20 07 03 20 01 03 20 07 04 20 01 04 20 07 05 20 01 05 20 07 06 01 19 9 Graph 1 - Brazil –Real Food and Beverage Retail Price Index (1990-2005) 1,5 1,4 1 2 IPCA-Alimentos e Bebidas / IPCA-Geral dez. 1993 = 1 1,3 1,2 1,1 1,0 0,9 0,8 0,7 0,6 Graph 2 - Retail Food Price Index1 / Wholesale Food Price Index2 Ratio (1994, aug = 100) 120 100 80 60 40 20 IPCA – alimentos e bebidas IPA-DI – gêneros alimentícios 10 Graph 3 - Agricultural Products Price Index3 / Wholesale Food Price Index4 Ratio (1994, aug = 100) 1,5 1,3 1,1 0,9 0,7 2005 11 2005 06 2005 01 2004 08 2004 03 2003 10 2003 05 2002 12 2002 07 2002 02 2001 09 2001 04 2000 11 2000 06 2000 01 1999 08 1999 03 1998 10 1998 05 1997 12 1997 07 1997 02 1996 09 1996 04 1995 11 1995 06 1995 01 1994 08 1994 03 1993 10 1993 05 1992 12 1992 07 1992 02 1991 09 1991 04 1990 11 1990 06 1990 01 0,5 IPA-OG produtos agrícolas IPA-OG gêneros alimentícios Graph 4 - Agricultural Products - Imports and Exports – US$ 109 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 Imports Developed Countries 1994 1995 1996 Imports Rest of the World 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Exports Developed Countries 2002 2003 2004 Exports Rest of the World 11 TABLE 2 - BRAZIL – Number of stores and participation in food retail by type of retail (1994 – 2002) Number of Stores Year Traditional 1994 211.965 1995 227.603 1996 238.671 1997 257.607 1998 1999 257.822 262.348 2000 269.438 2001 284.538 2002 282.989 Chains Independent 3.735 33.808 3.907 37.933 3.961 39.802 3.954 42.121 3.888 43.825 3.536 54.218 3.763 55.665 2.962 58.972 Total Brazil 249.508 269.443 282.435 303.673 305.534 319.428 327.192 343.965 344.922 Volume of Food Sales (%) Year 1994 1995 Traditional 14,90% 15,30% 1996 15,60% 1997 15,40% 1998 1999 15,60% 13,70% 2000 13,20% 2001 21,00% 2002 20,40% Chains Independent 44,60% 39,80% 44,90% 39,70% 46,60% 44,70% 37,80% 41,60% 42,80% 44,00% 44,70% 34,52% 43,85% 35,74% 45,10% 40,00% 44,40% 40,30% 3.884 53.196 Obs: There was a change in the methodology utilized in calculating the volume of Sales as of 2001, so that the values cannot be compared with the previous years. Until 2000, the volume of sales collected in the channels was focused on the categories audited by the various indices of ACNielsen. The new methodology considers the total volume of Sales of each channel, including all the categories that each channel sells, such as fresh vegetables and fruits. Source: AC Nielsen Census, apud Farina & Nunes (2002)