Page | 1 1. Introduction As the organizational culture of companies

advertisement

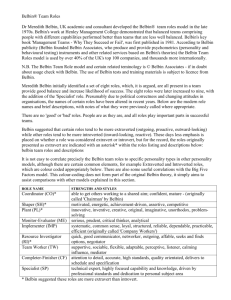

Page |1 1. Introduction As the organizational culture of companies keeps developing, there is much higher tendency towards teamwork instead of individual contribution. Teams seem to be recognized as an integral part of organizations’ inner workings. Professional skills and knowledge become more specialized and specific, leaving individuals unable to solve problems of higher complexity on their own. The response to this sort of challenge is assembling teams.The overall effectiveness of team work is also assumed to be better compared to other forms of work. Teams are viewed as able to improve flexibility in decision-making processes and boost innovation, commitment and resourcefulness, ultimately resulting in better performance (Schermerhorn et al. 2005, p. 194-197). In the ever changing climate of hospitality organizations it is important to have a better understanding of how team effectiveness might be increased. There are many areas relating to performance that could be examined, however, when it comes to team members it is important to pay close attention not only to the skills and expertise they possess, but also their individual talents, personality traits and behavioral characteristics. This research will focus on a specific hospitality organization, that is Hotel Rodopi located in Haskovo, Bulgaria. The leaders and members of the hotel have shared that there is a growing need for higher effectiveness concerning both individual and team performance. We chose to focus specifically on identifying member roles and how they relate to team performance. In order to do that, we will make an attempt at evaluating the aforementioned attributes and characteristics of Hotel Rodopi team members by applying the Belbin Team Role theory, as well as understanding and assessing the team’s effectiveness in terms of the individual roles presented. 1.1. Purpose of Research The aim of the study is to 1) explore individual behavior and team roles in a hospitality team (hotel Rodopi), as well as perception and evaluation of team performance using the Belbin Team Roles theory, Self Perception Inventory (SPI) and in-depth interviews to provide rich data on individual understanding and experiences. Since the team roles “define for each member his most effective way to contribute” (Sahu 2010, p.92), it is expected that an organization’s overall effectiveness is enhanced. This suggests that when a member’s personal characteristics (such as psychological traits and natural tendency towards certain roles) are identified and understood, then the team’s efficacy and success can be improved. Page |2 2. Literature Review 2.1. Defining Teams The importance of teams has been greatly emphasized due to the dynamic pace imposed by today's standards of organizational success. Nearly any institution is "fragmented" into teams to bring into being and extend the overall effectiveness and smooth sailing. The definitions of "team" may vary, for instance Katzenbach and Smith (1993) define a team as “a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, set of performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable" (para.2). Teams come as small or large, subjectively dependent upon a manager's decision, but the above definition suggests that they should be "small" in order to function as such. Other key components here are common purpose, shared responsibility and interdependent skills. On the other hand, Cohen and Bailey (1997) use teams and groups as equivalent terms, referring to teams as "a collection of individuals who are interdependent in their tasks, who share responsibility for outcomes, who see themselves and are seen by others as an intact social entity embedded in one or more social systems (for example, business unit or the corporation), and who manage their relationships across organizational boundaries" (p.240). Similarly to Katzenbach and Smith (1993), Cohen and Bailey (1997) view mutual responsibility and correlatedness (of skills and tasks, respectfully) as integral elements, however the latter authors affirm the social factor as well. Using groups and teams interchangeably is convenient since groups differ in terms of their level of interdependence and integration, and a number of researchers tend to refer to groups that have a higher degree of „groupness” as „teams” (Cohen&Bailey 1997, p.241). The following is a comprehensive enough definition of teams viewed as groups: ‘A team is a group of professionals who work together to produce products or deliver services for which they are mutually accountable. Team members share goals and are mutually held accountable for meeting them, they are independent in their accomplishment, and they affect the results through their interactions with one another. Because the team is held collectively accountable, the work of integrating with one another is included among the responsibilities of each member (Glover 2000, p.39). 2.2. Team Characteristics The team characteristics vary: they may concern organizational structure, individual contribution or Page |3 team processes. They include a plethora of factors, such as trust, communication commitment, clear purpose, suitable leadership, distinct roles and more (Mickan and Rodger, p.2). For this study’s purpose it is important to focus on relevant members and distinct roles. Assembling and identifying relevant members is about finding the right mix or balance of diverse skills, interests and backgrounds within the team (Mickan and Rodger 2000, p.3). Once these personal differences are established, individual roles that are suitable and relevant can also be assigned. 2.3. Role Distinction: Belbin Team Roles The term team role is associated with manners of individual behavior, contributions to the team, and interconnectedness at a professional setting (Belbin 2010, p. 24). It is important for team members to have established roles, in order for the team to work at its best effectiveness. These are often taskoriented roles assigned but what needs to be looked at is how each individual member can fit in a certain role. The team roles identified by Belbin are a tool for understanding behavioral strengths and weaknesses of individuals in a workplace environment. As Belbin states, „A team is not a bunch of people with job titles, but a congregation of individuals, each of whom has a role which is understood by other members. Members of a team seek out certain roles and they perform most effectively in the ones that are most natural to them” (http://www.belbin.com/rte.asp?id=8). Belbin makes a distinction here between two types of roles: formal (job-title, assigned roles) and natural, which concern behavioral attributes and personal characteristics. According to Sahu (2010), these natural roles depend on certain psychological characteristics, such as introvert vs. extrovert, calm or strung, levels of intelligence, dominance and submissiveness, as well as some other facets – instinct to trust or suspect others, maturity level, tolerance of uncertainty, to name a few (p.92). The following table gives a compact description of the nine roles as originally identified by Belbin. Page |4 Source: Belbin Associates 2009, p.9 2.4. Role Balance The roles that feel most „natural” would depend on each member’s pattern of behavior, contribution and inter-relatedness with others. Teams need to be comprised of balanced personality/behavior types (Loganathan, p.2). Determining that balance can be done in several ways, however, the most commonly utilized approach is to find out whether the team as a whole possesses all 9 Belbin roles within its members (natural level, score 70 and up). If they do, as per Belbin’s understanding, „the team is said to be balanced, with the implication that a balanced team will be high performing” (Senior 1997, p.246). Having all 9 roles present in a team, however, does not mean the team would necessarily have 9 members; each member might embody several different roles (Pollock 2009, p.45). 2.5. Team Performance Though the success and efficiency of a teams’s performance is heavily reliant upon the talents, skills and behavior of the team members (identified by the natural roles), performance is hard to define and measure. There are many aspects that can be looked at, for instance leadership, Page |5 motivation, goals, competence, etc. This is why some researchers recommend that performance criteria are set by the team: „..Asking teams and individuals to rate themselves on whatever factors are determined to be important is a good way to approach "immeasurables" like customer service, teamwork and communication skills” (Galpin 1994, p.245). Katzenbach and Smith (1993) argue that „agreeing on the specifics of work and how they fit together to integrate individual skills” sets a common approach and boosts team performance. Each individual has strong and weak points which express their personality, talent, background, etc. and part of finding the best common approach means finding out „who is best suited to each task as well as how individual roles come together” (p.6). The authors advise that team goals should not be always reflecting (or be same as) corporate goals and that team member skills, not their positions, should decide their respective roles (p.9). Belbin’s understanding is similar, though he does not center solely on individual skills; the factor of utmost importance to him is rather individual behavior: „The crunch question in the long run is not, therefore, what a prospective employee knows, or what specialist skills are possessed: what matters most, given a fair field of adequately qualified candidates, is how the chosen person is going to behave” (Belbin 1993, p.19). Hackman also links effective performance with behavior and implies that under appropriate management various behavior types can be used in a beneficial way: „Many types of behavior can be productive; therefore, those who create and lead teams should focus on creating the right conditions for them to succeed, rather than trying to manage their behavior” (quoted in Pollock 2009, p.44). Belbin’s specific role differentiation and understanding that an effective team would contain separate roles that are unambiguous, distinctive and contrasting of each-other, suggests that higher role clarity within the team would bring higher effectiveness, resulting in better team performance. Thus, role clarity is a key factor that can determine a team’s performance. Conversely, points that may be problematic concerning team roles would be role ambiguity and role conflict. The latter is present when a member is not capable to react to role expectations which are in contradiction (conflict); role ambiguity signifies a member’s doubtfulness about expectations of his/her role (Schermerhorn et. al 2008, p.185). Parker (2008) distinguishes twelve characteristics of effective teams, among which are clear purpose, informality, participation, listening, consensus decision, and clear roles (pp.19-20). The latter will be looked at in further detail, since it has a significant relevance to our topic of examining Page |6 team performance in terms of member roles. 2.6. Role Clarity Similarly to Belbin (1993) and Schermerhorn et al. (2008), Parker (2008) maintains that „The concept of role goes beyond a listing of tasks to the expectations a specific team member has about his or her job and to the expectations that other team members have about that job. Since effective teamwork involves task interdependence, agreement on these expectations is extremely important” (p.48). This statement clarifies further that without accordance, and clear mutual understanding of expectations the team performance is not at its peak. The significance of roles needs to be recognized by leaders and members to heighten the success rate of the team. Conflict is frequently perceived by members on the emotional /feeling side, though in reality is rooted in procedures and roles. This role conflict and role uncertainty could bring noticeable stress upon the team, leading to „lost productivity, dissatisfaction, and a tendency of members to leave the team” (Parker 2008, p.49). On the other hand, team roles and tasks are well defined, interpreted and clarified when members do a few or all of the following: - Work to get the team to agree on higher standards for members’ professional contribution; - Have the desire to work above and beyond their formally delineated roles if needed; - Candidly communicate among each other and negotiate their expectations; - Arrange that tasks are assigned evenly among themselves (Parker 2008, p.52). 3. Methodology This research is comprised of several principal stages: - Literature review; - Comprehensive case study of a team; - Collecting individual data through inventory and interviews; - Evaluation of team performance by interviews with senior manager and other members of the team; - Analysis of the information gathered. Page |7 3.1. General Research Approach Before determining the specific method to utilize for data collection, several well-known research approaches were looked at: Survey was decided against as it would not accomplish the goal of gaining meaningful thorough information, and also because the participants are selected informants, not random people. Action research, according to Saunders et al. (2009) , needs a long-duration research to verify data, and is considered too time consuming (p.141). Other research strategies, such as archival research and ethnography are quite obviously unfit for this study’s purposes. They require previous records or references, or are explored in anthropological context (Saunders et al. 2009, p.141). The approach found as most useful and appropriate was the case study method. 3.1.1. A Case Study Method The case-study approach was chosen as it allows for a more in depth, detail-oriented investigation of a specific type of team and its team members. The purpose is to gain an individual and rich frame of data, which can be achieved by utilizing open-ended „how” and „why” type of questions. A case study method is also considered relevant when the researcher cannot manipulate the participants’ behavior, and/or when a contemporary phenomenon is targeted within a real-life context (Yin 2003, pp.5-10). In this research, contextual conditions need to be examined, because the team roles and performance cannot be scrutinized without the context they are shaped, developed and occurring in, i.e. the hospitality/hotel settings. 3.2. Sample Selection The sampling method chosen was purposive sampling, as the data could only be gathered only from specific informants that were pertinent to the study. Purposive sampling is particularly useful in case study analysis, for instance when examining specific individuals or groups, construction of attitudes and „the role they play in dynamic processes within the organization or group” (Given 2008, p.697). Key informants are indeed the appropriate and favorable candidates for interview. Creswell (2007) proposes that in order to gather qualified participants that will provide most useful and applicable to the research data, purposive sampling (criterion-based or critical case for example) strategies should be employed. Creswell emphasizes on selecting participants willing to provide information in a candid and open manner (p.133). Page |8 For this research, the selected key informants were all team members of the hotel who were part of either the management or administrative personnel. They were singled out to take part in the study, because they are the people directly engaged with the hotel’s activities and organization; have more personal involvement in events and coordination; are most intimately familiar with the work dynamics, in comparison to the remaining (service) crew. The formal, professional roles they had were those of managers and assistant managers, receptionists, proprietor/owner, accountant, sales and service associates. Their total number was 12 and it encompassed all possible employees of middle and higher level. As rule for purposive sampling, paying attention to one or a few groups or individuals is considered more applicable. The sample size involved does not hold the same level of significance as in quantitative research, as the purpose of qualitative research is to gain insights into certain processes and practices, which are predominant for a particular venue; „in order to gain insights, qualitative researchers usually strive to extract meaning from their data” (Onwuegbuzie & Leech 2007, p.106). 3.3. Data Collection Technique Data was collected via the following tools: questionnaire: Belbin Team Role Self-Perception Inventory, as well as qualitative, open ended interviews concerning roles, role clarity, teamwork and performance. Each of these is discussed in detail below. 3.3.1. Belbin Team Role Self-Perception Inventory (BTRSPI) The BTRSPI (see Appendix) includes seven sections, each of these being associated with ten behavioral statements. Every statement refers to a specific team role (plus a control statement). The participants’ role predilection depends on the distribution of points for each team role statement and how many times it was selected. The responders are not informed of how their preference is determined. They are asked to make their individual choice by assigning ten points to any of the statements. The participants can give more points to statements that mirror best their beliefs, views and feelings. They are asked, however, to stay away from excessive selections, for instance either choosing to assign all ten points to a single statement, or assigning one by one points to each of the statements (only one point per statement). 3.3.2. Validity and Reliability of the Belbin Team Role Self-Perception Inventory It is argued by Furnham (1993) that the BTRSPI is an ipsative instrument mainly that it is a forced choice answer, which misrepresents in a way the responder’s choices. Furthermore, the author argues that „little evidence of the psychometric properties of the test are offered” (p.246). Another Page |9 issue that Furnham (1993) points out is that the inventory is „neither theoretically nor empirically derived” (p.247), in particular that theoretically significant characteristics, such as neuroticism /a commonly accepted dimension of personality/ might go unnoticed or glossed over, and that there is no certainty all team roles are included in the inventory (p.247). Belbin counters Furnham’s argument by suggesting that the team roles should not be viewed so much in terms of as personality traits, rather a cluster of behavioral ones. The BTRSPI measures behavior, while personality is only one among many factors influencing it, namely mental abilities, experience, field constraints, role learning, current values and motivations. Belbin sees behavior as a provider of „most useful and verifiable information regarding an individual to a recruiter, manager or consultant, as well as to the individual concerned...Behaviour is observable and can be interpreted and used to predict future reactions and conduct”(Belbin Associates 2009, p1). Essentially, instead of gleaning knowledge of personality traits the BTRSPI examines behavior to single out team roles groups or clusters, which represent an individual’s behavioral input to the work organization. The Comprehensive Review of Belbin Team Roles points out the difference between a personality test question and a BTRSPI question: „For example, you might find a question in a personality test along the lines of: ‘When I’ve made a decision about something, I still keep wondering whether it’s right or wrong.’ Here, the focus is on how the individual thinks and feels. By contrast, the BTRSPI asks questions like: ‘I can be relied upon to finish any task I undertake,’ focusing on practical contributions an individual might make” (Belbin Associates 2009, p.1). Additionally, while personality is relatively stable and unchangeable throughout life, behavior is quite fluid and variable. Thus, the individual does not exhibit a certain role, but a combination of roles: preferred, least preferred, or manageable; „Whilst an individual may claim to prefer or enjoy a particular role, it does not necessarily mean that they can or should play only this role (p.2). Regarding the ipsative nature of the BTRSPI suggested by critics, Belbin’s argument is based on the idea that a responder’s choice is not a forced but in fact restricted one: „self-rating on independent scales yields little of value in industrial and occupational settings”, thus „some restriction of choice [was] operationally desirable” (Belbin Associates 2009, p.4). This statement then proposes that the inventory is indeed a generally ipsative tool. The responder would make a choice between several statements that serve to evaluate various characteristics, thus making them interdependent of each other to some extent. As Aritzeta et al. (2005) finds, „correlations are ‘forced’ due to scores for one variable influencing the scores for another (p.13). P a g e | 10 Nevertheless, the scores are not entirely ipsative because they don’t make up a constant value across sections. There is only one statement per section that would reflect a certain role, and so same-scale scores are independent of each other, but interdependent with other-scale scores. Simply said, the instrument is „ipsative within its sections (since scores always sum to 10) but not between its sections” (Belbin Associates 2009, p.4). 3.3.3. The Interviews Gaining a deeper and more comprehensive understanding requires that participants are offered not only a reasonable range of possible answers, but given the opportunity to tell the story of their own experiences. Standardized, open-ended interviews were used to provide a more personal and meaningful insight, working directly (face to face) with the respondent, leaving the door open for follow up questions when appropriate. This method also encourages the responders to share as much specific and elaborated information as they want to, as well as fully express their personal experiences and standpoints. The interviews attempted to explore behaviors, feelings, opinions and values. Their focus was on members’ individual experiences within the team, members’ perceptions and views of their own roles, as well as how the members evaluate the team’s ability to perform. As explored earlier in literature review, team performance can be viewed in terms of various criteria depending on what aspect of it the research wants to focus on. There are many characteristics possible to take into account, so the performance-related questions were centered around the team members’ evaluation of its efficiency, factors they believe are indicative of such efficiency, as well as possibilities for enhancement. However, since this study has a special interest in roles and performance, some of the questions regarding performance also involved roles. Literature review illustrates that clear understanding of member tasks and roles is considered essential for effective teamwork by both Belbin (1993) and Schermerhorn et al. (2008), along with Parker (2008), the interviews contained questions pertaining to clarity of roles as well. Thus, performance could also be reviewed in role clarity terms. Prior to conducting the actual interviews, the participants were explained the interview’s purpose, format and approximate duration, as well as the terms of confidentiality. 3.3.4. Validity of Interview Data: The interviews aim at gathering insight from personal opinions and experiences mainly to gain data of first hand experience. Responses would contain some P a g e | 11 subjectiveness, but that is always expected when personal involvement is at stake. Other factors, such as location, culture or psychological pressure could have influence as well. However, it is important to remember that in-depth interviews concerning personal and empirical experience can provide the rich, profound data needed to explore individual differences in terms of team roles, and role and team work perception. 3.4. Limitations Results not generalizable: Since small sample was selected and it was not a random sampling procedure, generalizations would not be so relevant here. The nature of open-ended interviews generally entails responders fully expressing themselves and in greater detail, which makes it more challenging for researchers to identify corresponding or identical themes from the interview transcripts. This was, however, a minor „weakness”, as the method necessary for this research was one that would allow for thicker and richer qualitative data from the participants involved. Linguistics: The chosen language for the interviews was Bulgarian, the native language of all interviewees. While they all spoke English to various degrees, it seemed more appropriate to use their mother-tongue, in order to avoid confusion, misunderstanding of meaning, other misinterpretations, or (for some) inability to express themselves as freely, eloquently and extensively as possible. Furthermore, most of the responders seemed more comfortable, at ease and willing to share in their first language. Their preferences along with certain cultural awareness were also taken into account when determining the language of operation. Time Consuming procedure: The aforementioned open-ended interviews created a more timedemanding process, due to its sometimes narrative responses that required filtering. The language considerations also resulted in extra time allocated to translating the extensive bulk of data compiled. 4. Outcomes and Analysis 4.1. Roles (BTRSPI and Interviews) The questionnaire’s team roles showed up in order of preference. The most preferred roles, i.e. those with highest scores and order of preference, were singled out and paid further attention to. Since they are meant to be the most suitable and desired roles, they seem most appropriate to P a g e | 12 explore and compare with the roles the participants describe for themselves. In this way, patterns of similarities (or discrepancies) between the inventory and the members’ self role-perception can be traced. The BTRSPI results collected showed that the team was composed of two plants, one implementer, two coordinators, one specialist, three team workers, one shaper, and two resource investigators. The team was lacking two of the roles: completer-finisher and monitor evaluator. As reviewed in the theoretical chapter, there is an implication that a team which has all 9 roles present is a balanced, and therefore successful and high performing one (Senior 1997, p.246). Although in our team’s case two roles are absent, it can be argued that it is still complete, in the sense that the secondary roles (less preferred, but closely following the most preferred ones in scores) contain those missing roles. As per Pollock’s (2009) statement, it is possible for every member to represent more than one roles (p.45). Whether or not this team can be considered fully equipped with all nine roles and high functioning by Belbin’s standards, it is more intriguing and significant to look at the individual inventory scoring and how it fits the individual role perception unfolded during the interviews. Notably, many of the inventory roles’ characteristics seemed to match with the descriptions the participants had given about themselves and the way they see their workplace roles. For instance, a responder who talks about ideas, and enjoying the coming of „unconventional ideas to life...ideas that might be considered outlandish or unaccomplishable by many...” had his highest scoring for „plant”, a role that entails high imagination and intelligence, encouraging, individualistic and unconventional. Another participant, whose most preferred roles came up as „specialist” and „implementer” made the comment that these roles were as if „written” for her; she also defined her role as objective thinker, withes accuracy, tracking process down and analyzing, as well as fixing errors being focal points of her job. These descriptors seemed a good fit with the two inventory roles presented, as they involve organization, systematic and effective execution of tasks and some evaluation (Belbin Associates 2009 and Loganathan 2011, p.4). This participant had also stated that she has „very narrow, specific assignments that pretty much only I can perform,” which is again, consistent with the „specialist” concept. There were a few more seemingly accurate instances, one of „shaper”, whose characteristics are „challenging, dynamic and driven” (Belbin Associates 2009, p.9) as well as demanding and active, a person who sets progress in motion and weighs in heavy on decisions (Loganathan 2011, p.4). According to this responder’s interview, his self-image does reflect that: he is a leader, monitor of P a g e | 13 action, organizer, stimulator (concerning people, their motivation and ideas). High involvement and strength in decision-making is also this responder’s special line as he shared that „whenever an employee happens to have to make crucial, eventful decisions, often I would take upon that employee’s duties and make the decision myself.” He also admits that he needs to pressurize, sanction or reproach supervisees at times, which falls within the weak points of the „shaper” role as listed. Given that this informant’s formal role is that of a manager, it can hardly be viewed as a weakness, it seems that it isn’t so much a personal choice or trait of behavior, rather a pre-requisite for an effective execution of professional responsibility. Other similar matches were of „coordinator” and „resource investigator,” as the informants view themselves as mediator and regulator, conflict resolving and thus enabling agreement, as well as personal inclination and job requirement for networking, contact initiations and fostering, respectively. The rest of the scores could be ruled either as a potential fit (for 4 of the participants), or not a proper match (3 of the participants), as compared against their personal opinion of their relevant roles expressed both during the interviews and after taking the inventory. Examples here include a highest score for „team worker” which is socially oriented and team-supporting, but indecisive and conflict avoidant. This participant disagreed as he considered himself a strong decision maker who would not care much about potential conflicts, but focus mainly on what’s fair and efficient. Another member, whose role came up as „implementer” found certain traits (such as rigidness and dislike of the unproven) irrelevant. Some of her interview responses, however, do seem to back up the presence of such traits. When asked to evaluate her team’s performance, the participant states: „I personally rely solely on people who’ve already been tried and checked, so to say; with them the results have always been excellent. I’ve given chances to new people as well, but frequently been too disappointed..." Mismatches and moderate matches of this kind could be due to several factors: - people often have a tendency to present themselves in an image they desire but have not quite accomplished yet, in other words wishful thinking; - the participants might not have exhausted (or extensively illustrated) all the aspects of the main roles they see themselves playing; - the previously discussed „restricted choice” proclivity of the BTRSPI, leaving options for statements that have to be allocated an x number of points; - personal patterns of behaviors that may have come to light while taking the questionnaire, but not taken into account during the interviews. P a g e | 14 4.2. Role Motifs (Interviews) The interviews demonstrated in-depth, comprehensive accounts, understanding, evaluation of roles of self and others. Among the key themes that emerged from the informants’ responses were: role and task designation, accountability, organization, fairness and objectivity, differentiation of responsibility, communication, expectations. In regards with team roles and team work, a recurring concern was individual accountability and task assignment: for the administrative unit mostly an issue about even distribution of responsibilities and equal participation of team members. A few seemed content and uncritical, with the understanding that „...we are here to work as a team. The work cannot always be equally distributed – it isn’t cheese to be cut in identical portions. Everyone participates according to his or her ability. When someone is on a sick leave or has holiday time, their job needs to be taken care of by other members anyway, and again, it doesn’t get spread out evenly, rather depends on who has how much work at that moment, or who is most available, and of course who is also qualified enough to step in.” Participants in this category surmised that a member’s inefficient or passive participation might be due to other contributing circumstances, such as miscommunication or misunderstanding about tasks. The overall priority for these informants seemed to be what gets accomplished in the end, regardless of who has done what and how much. Other statements, on the other hand, expressed strong critical views, such as „Everybody [should be] fulfilling their responsibilities, instead of having colleagues who can get away without being held accountable”, „Some people are given too many responsibilities, others are favoritized by certain supervisors and act like they are invincible...Usually, those who do nothing point themselves out as the most hardworking and take credit for achievement”, and „Sometimes the work engagements get distributed unrightfully.” When asked the question „Have you ever been asked to handle a task that you thought was not your job to do?”, almost all answered positively; surprisingly, now some of the above-cited informants indicated that they did not mind and weren’t bothered, but made remarks about expecting to be paid extra and preference to „sticking to what’s been outlined in my contract, and not having to worry about outside duties.” Overall, several of these responders’ demeanor suggested some indignation and resentment when they believed their colleagues were not contributing. Nevertheless they were willing to accept extra workload if it was not someone else’s assignment, and if they felt properly motivated. The responses gathered from the managing crew were quite different, the predominant concept P a g e | 15 reflecting team work as a whole and the consequent team results, without placing much value on individual contribution. While management acknowledged that there are instances of employees being given responsibilities that normally others handle, or that are outside of their range of duties, they also saw it as a natural challenge that is to be expected. Their views were that „members need to get along well and efficiently replace each-other, or do whatever is needed to get the job done, even if it means sometimes taking on tasks outside their normal routine” and that it is „all part of being able to work in a team. It’s not always about doing your everyday tasks, you have to be able to see the big picture and work towards best end-results, this is a top priority we all have here.” One of the interviewees who took the same stance added that task distribution and participation balance needs to be monitored and regulated to reduce tension within the team and to ensure everyone performs within the capacity of their professional role. This resonates with Parker’s claim that role conflict and ambiguity could have negative consequences of lost efficiency, frustration, and quitting members (Parker 2008, p.49). The informants in the management group also shared that they too were facing the same challenge of having to complete already assigned tasks themselves, for example when an employee has executed internal orders inadequately, the job would fall to the supervisor and it „wasn’t pleasant because such changes can lower the leaders reputation, lead to losing time and finances, and I have to fix the mess on someone else’s behalf.” These situation were perceived by this group as „part of the job” , even if unexpected and unplanned. As far as the assignment distribution, opinions vary, though favorable ones prevail – several responders (both management and administrative staff) feel that it is a tough call to make that depends on personal perception and how much willingness the members have to support the team. The leaders’ answers were more thorough for this question. They touched on the subject of individual knowledge, skills and personality: type and amount of work vary but so do paychecks; „...some employees are able to take on more responsibilities and do a magnificent job, others get easily stressed out or simply aren’t competent enough to handle the pressure. But we don’t abuse people in this way- if someone carries more weight this time, another one will replace him the next time and so on.” Another factor was circumstances („when we have a hectic event it can happen quite often that a member or a few members would have to balance things off”). P a g e | 16 4.3. Clarity of roles All informants were also asked whether they had a clear understanding of their roles, and whether the (role) expectations of each team member were clear. Most responses here were positive, albeit conditional, and indicating that one role would actually contain a few more roles that are not „official” or formally agreed upon. Statements made to illustrate that point included: R1: „For the most part, my understanding is clear, however there are times when you have to kind of step out of your own role’s box and contribute a bit further”; R5: „Yes, I do, but it took me some years to get that understanding, because my position involves several different roles all in one that it might seem chaotic and unclear to the untrained and inexperienced professional”; R8: „I should think my role is quite clear, but when I am in a certain situation I’ve found myself having to play other roles as well – particularly if I am unhappy with how it’s been handled by my employees or the results are lacking”; R10: „I feel my role is clear on paper, but in reality I am presented with many other roles that I’m not always sure how to deal with.” Clarity of roles turned out to be a quite ambiguous and complex matter, requiring a lot of flexibility, knowledge outside the individual specialized line. Many of the positions (especially the higher ones) would not allow for „tunnel vision” specialization, and demand good understanding of the other members’ responsibilities instead. Interdependence and ability to replace colleagues and supervisees, or swap duties seemed an essential part of the work here. Regarding expectations and clarity of everyone else’s roles, the majority of answers were again positive – for one’s own role, but not so favorable when it came to evaluating other members’ understanding. Responders from the administrative unit felt that there were members who „stray away from their roles, picking tasks they enjoy and finding excuses to pass the rest to other people, or just ignoring those tasks until someone else takes them” and that „sometimes people are unhappy about their roles and don’t quite agree with the expectations..but I think everyone is more or less familiar with what their coworkers (and themselves) need to be doing.” Another problem pointed out was the lack of open communication when difference or disagreement of expectations arises: „What management expects might be clear to management, but then the employee has a different expectation and you can see how problems and conflicts might arise...Discrepancies in opinions and understanding about many things (including expectations) are often left undiscussed and these issues never get ironed out.” P a g e | 17 Responders from the management block spot other issues, such as occasional over involvement of a member with other members’ efficiency, and judgment passing. Although it is certainly challenging to ensure everyone has identical, or at least similar, expectations, there are written ones that are thought of as quite encompassing, and serving as guidelines: „There are clear, formal expectation for each member. They are delineated in the occupational characteristics for each person who works here. This paperwork is signed by the employee who agrees that his/her duties are clear, and that the repercussions of actions not fitting these characteristics are also clear.” Still, formal expectations do not equal expectations in practice, but those contract characteristics are the base for the commonly occurring assignments and responsibilities. 4.4. Team Performance The participants were asked to name the factors they believed were indicative of successful team performance, then evaluate their own team’s performance, and finally suggest improvements. More than half of the informants interpreted achievements and goal realization as pointers for a rewarding team performance. These goals were specified as „positive results in numbers – new visitors attracted, returning visitors, high revenue.” Occupation and consummation rates as well; according to one of the managers, „if occupancy is 30% throughout the year, that’s enough for the hotel to sustain itself, and we are aiming for 60%. That can only be achieved through a team that is effective and works well within.” Many of the interviewed considered the significance of attitudes and team relations. These meant mainly the following: responsible and reliable attitude, social and team work skills, collective support/mutual assistance, fair relations, and „effective interactions among all workers, high team spirit and cohesion.” Various factors that would fall under the broader umbrella of motivation were also discussed, namely appreciation, positive evaluation of the work done, suitable remuneration, and the professional and personal growth of all members. Other individually mentioned factors were clear purpose, professional knowledge, rational planning, adequate distribution of work within the team, ability to make unbiased judgment and critical evaluation, as well as good work atmosphere. The factors that were consistently repeating within the participants’ answers evidently involved results and achievement. However, these components alone are not really „factors”; they can be only viewed as the end-product of other conditions. We know what the ultimate aims and goals are, but how are they to be reached? While there are certainly specific procedures and actions outlined and executed, what are the core values and dynamics that would make the team function as such in its truly blossoming, effective form? This is where those seemingly more subtle and peripheral factors of attitudes, relations and motivations come at place. They are the driving force behind P a g e | 18 beneficial task completion, aptitude of operation, and even individual contribution. When asked to evaluate the performance of their own team, many participants used automatic, overly simplified adjectives, such as „decent”, „pretty well”, „functions quite effectively”, „good and efficient”, „strong”, „okay”, „competent, capable, skilled.” Other members determined it as „meeting the demands” and doing „what’s required and desired.” They avoided elaboration and appeared uncomfortable sharing much detail on the matter. One participant was over the top negative, and seemed as though she did not feel comfortable or part of the team. Conversely, two informants referred to their team as a „family.” While they did not present the team performance as flawless, they had a sense of belonging and genuine confidence that no matter what the team goes through, it stays bonded and overcomes the hurdles. Attitude and relationships again emerged as a theme: responders wanted to talk about their behaviors and treatment, „We do get involved in disagreements as anyone would expect, but it’s never been ugly or spiteful”, or fellow members traits: „Most people who work here are good people, diligent, hardworking and sincere”, „those who have earned our trust and proven their worth, they really boost our performance.” Evidently, these participants felt strongly that quality of team work and performance depends largely on personal characteristics and relations. According to Mickan and Rodger (2000), „Good social relationships maintain effective teams...members who are empathic and supportive of their colleagues offer practical assistance, share information and collaboratively solve problems” (p.206). A responder brought up the issue of diversity, stating that the team had a „good mixture of diverse backgrounds, professional experience, temperament and humor...All of it benefits the team in so many ways, adds to its character, makes it fluid and wholesome.” Team diversity is among Gratton and Erickson‘s (2007) 4 crucial team traits: „Diverse knowledge and views can spark insight and innovation”, but differences in perspectives may lead to unwillingness for knowledge sharing (p.6) Another informant of management who also had a supportive evaluation of the team performance, focused on an aspect he considered more impactful for enhancing visitors and profit numbers than the work of the team itself: the hotel’s geographic location, as the city is not a prime touristy destination but expected to become with new roads and monuments opening up. In regards to the improvement of team performance, responsibility and conscientiousness came up twice, as did technical equipment and more updated devices. Participation was a highlight, as several responders expressed a need for more involvement and more regular brainstorming, „active P a g e | 19 participation, understanding that team means „we” not „I.” Other suggestions included friendlier environment („people need to relax more, smile more and make the effort to get along...”), improved communication, setting and keeping track of efficiency goals, unbiased treatment. Management discussed assessments and plans for advancement, as well as some additional training („...learning of foreign language, any language available that an employee is interested in. This training would involve all, so that we can be more effective, attract more foreign tourists and become a stronger competition.”). Since as mentioned before the destination was not deemed sufficiently developed, responders from the management unit also shared a desire for developing their own tourism and sports program for the hotel’s guests if resources and good co-operation are found. 5. Conclusion The BTRSPI worked well for determining some behavioral tendencies, talents and weaknesses of the participants. However, there were some gaps between behavioral roles the inventory suggested as preferable and members’ formal roles and personal awareness of their representation. Task distribution/responsibility: Managers came across as more willing to take the burden of additional work, they take it as part of the job, and not a cumbersome, aggravation; from their claims it can be gleaned that they see no difference between „extra” work and regular work. This attitude differentiates them from most members of the supervised staff who struggle with the concept of doing work that they do not consider their job or formal responsibility. The responses concerning role clarity were also mixed; though roles are far from clear cut, there is no big confusion or chaos reigning. The members show a good primary orientation at the very least, and seem to be able to find their ways to cope with such ambiguity, even when they do not feel entirely confident..Distribution of work seems fair, as far as the nature of such hospitality work that requires flexibility and interdependence allows. Though there was apparent discontent from some of the administrative staff, the validity of the complaints was questionable, moreover they were directed more towards other colleagues judged as inefficient. Management had attempts and effort to enforce fair and unbiased designation, though it may often be unequal (depending on individual abilities for contibution). When determining whether roles and tasks are clarified and well-defined, Parker (2008) considers several indicators; among these are the desire to work above formally designated roles (p.52) – one that management has demonstrated but is missing among the lower P a g e | 20 level employees; and evenly assigned tasks (p.52) – a condition questionable and open for interpretation in this case study. All of the above influences performance, which was assessed by some responders as built upon attitudes and relationships, motivation, participation, diversity, and characteristics of team members – features that were also hinted as problematic and needing improvement. Further exploration would involve evaluation of the team on each of these particular factors and coming up with strategies for improvement. In relation to roles specifically, the communicated issues of role clarity and conflict that hinder performance because of expectation discrepancies, confusion between formally drafted duties and duties in practice, attitudes and behavioral tendencies.