ROUGHLY EDITED COPY CONFESSIONS 1 CON1

advertisement

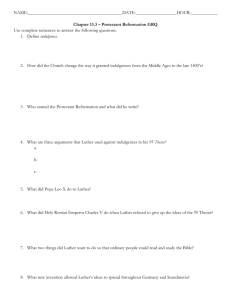

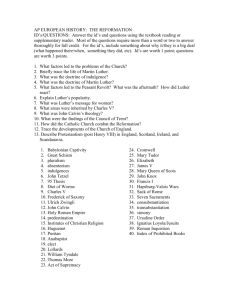

ROUGHLY EDITED COPY CONFESSIONS 1 CON1-Q023 JANUARY 2005 CAPTIONING PROVIDED BY: CAPTION FIRST, INC. P.O. BOX 1924 LOMBARD, IL 60148 * * * * * This text is being provided in a rough-draft format. Communications Access Realtime Translation (CART) is provided in order to facilitate communication accessibility and may not be a totally verbatim record of the proceedings. * * * * >> DAVID: I appreciate all that has been said about the ecumenical creeds, but now I would like to ask a question about the first of our Lutheran Confessions. Could you please indicate some of the developments that shaped the historical context surrounding the Augsburg Confession and explain to us how this confession came about? >> DR. KLAUS DETLEV SHULTZ: Yes, David. The Augsburg Confession came about in June 1530. However, in order to understand the circumstances around that event of 1530, we need to go back, probably about 13 years, and began with 1517, when Luther posted the “95 Theses” on the church in Wittenberg and thereby setting off The Reformation as a movement in all of Germany. What Luther addressed at the time was a penitentiary system, that system that did not address confession and absolution properly and did not demand from those people who came to confession and absolution in the churches that cont that was necessary to receive absolution. Now, Luther addressed The Reformation theologically, but it took hold in Germany also as a social and political movement. But in order to understand what the Augsburg Confession is all about, we should see The Reformation, first of all, as a theological movement. Now, let’s go further on to the year 1521. Then the Edict of Worms was passed by Charles V. Now the Edict of worms goes back to 1520, the diet of worms, when Luther was invited to that city of Worms to express his point of view about his writings and his theology in front of the emperor, a young emperor, Charles V. Charles V was curious to hear about what Luther said theologically, and he gave him a chance to present his view, and above all, to recant all his writings. Luther stood up and said the famous words, here I stand. Meaning thereby, that he was only willing to recant and retract all his writings and theology if he was proven from scripture and by common reason that he was wrong. Now that, of course, could not be done. And so the result was that in 1521, the Edict of Worms was passed over Luther and all his writings. That meant nobody was allowed to further The Reformation, to offer Luther shelter, and to promote his writings and theology. We have, therefore, here a very important step toward The Reformation. Luther had written numerous articles and numerous writings already by that year 1521. These writings were disseminated, and thank goodness, that the printing press by Johann Gutenberg was already innovated and made public so that Luther became a best seller in terms of his writings. As the years ensued after 1521, numerous attempts were made to find some solution between those that supported The Reformation and Lutheranism and the sympathies of Charles V, namely, to further again the Roman Catholic Church in Germany. There was one territorial ruler, the *Elector John Frederick the Wise of Saxony. This emperor favored Luther's theology, though he himself was a great fan of collecting relics. But *John Frederick the Wise saw in Luther a person that also promoted the German cause, and the Elector John had a great chance, here, to present his view in front of the Emperor Charles V because he had the status of an elector, a very important status in the territories of Germany because not every ruler of a territory had that privilege. So *Elector John Frederick had to be taken seriously by Charles V and probably because of his status as an elector, Charles V was willing to listen more carefully to that elector than perhaps to anyone else. And so he offered refuge to Luther in the territory of Saxony at Wittenberg, supported the new university and made Luther professor there and also brought a young man called Philipp Melanchthon to Wittenberg, a young scholar who was asked to teach the biblical languages. But he was soon advanced to teach also theology. One important event is 1528, the Diet of Speyer. Here we have the name Protestant emerging for the first time. Because Charles V expected at that diet that all the territorial rulers of Germany should further the Edict of Worms. That means that they should rigorously pursue all those who had sympathies for Luther and his theology. *Protestatio is called their document and their position. They are Protestants and refused to do that what Charles V said. So the thing still remained unresolved by 1528, and the events than led to the Diet of Augsburg in 1530. Two important occasions brought this diet about. One was the Ottoman Empire was spreading to Europe and was endangering the core of the empire of Charles V. Vienna, already, was besieged by the Turks by 1529. So the emperor needed as many supporters as possible to support him to drive back the Turks from the empire that was his. Another problem was also France. The king there was rising up against the emperor, and he, too, had to be addressed. So it was also a political occasion, this Diet of Augsburg. But he was also interested to hear exactly what the position was now of the Lutherans in Saxony and other territories where it had now taken hold of. So the emperor, Charles V, invited all Germans to come to the Diet of Augsburg. And he wanted to hear exactly what abuses they had addressed. So Elector John, the son of John Frederick the Wise, called together all important theologians. Amongst these were also *Justus Jonas and *John Bugenhagen, both very important figures who furthered the cause of The Reformation. Next to Luther and Melanchthon, these were very important theologians. So these four theologians then immediately went about to set up a number of articles that would relate to those abuses in the Roman Catholic Church that they as Lutherans had addressed and corrected. There is a lot of theology in the *Tourgau Articles. These are the other articles that they had compiled and presented in 1530, early in that year at *Tourgau. The *Tourgau Articles were taken to Augsburg and to be presented to Charles V. They were addressing the abuses only, which is very important to know because when the theologians and the emperor and other princes in free cities, all those who had sympathies for The Reformation, went to Augsburg. They soon discovered that there were other representatives invited to that diet who also had presented some of their statements of faith. For example, Zwingli, who presented his *Fideratio, an explanation of his faith and his theology. And then there was also the *Confessio Tetrapolitana, that confession of *Martin Bootse and also that of the four cities in southern Germany. Upon that notice of all these further documents being submitted, and especially that of the Roman Catholic theologian, *Johann Eck, the 404 Propositions, those statements that made allegations that Luther, Melanchthon, and other theologians of The Reformation were heretics. These all occasioned the Augsburg Confession itself to be written. The reason is that the *Tourgau Articles were not enough to put forward what the Lutherans all believed. It was more an apology, less a confession. And so a confession had now to be compiled. Melanchthon, being the main author because of Luther's absence, set about to write the Augsburg Confession. He had a number of documents to which he could go back to find certain theological themes that they had already purported elsewhere. For example, Melanchthon could go back to the *Marburg articles, those articles that were discussed at *Marburg between Luther and Zwingli. There, you know, Luther and Zwingli could agree on 14 articles. But when it came to article 15 on Holy Communion, they could not agree on the presence of Christ in Holy Communion. There was also another document, the *Schwabe Articles. These were articles compiled by Luther, Melanchthon, and other theologians, one of them also *Johannes Brentz, that theologian who furthered The Reformation in southern Germany later on, and also responsible for much of what was said in the Formula of Concord. Melanchthon took the *Schwabe Articles, together with the *Marburg Articles, and then in addition to that, Luther's great confession of the Lord's Supper of 1528, and drew from these a number of articles, the articles that are now presented in the Augsburg Confession in the beginning, those from Article 1 to 21. Articles 22 to 28 are those that we have from the *Tourgau Articles. This Augsburg Confession was repeatedly passed on to the theologians present at Augsburg itself. But Luther himself also remained in correspondence with Melanchthon finding out exactly what was being said and written. And he approved of the Augsburg Confession finding that it succinctly brought to the point all those questions that Lutherans had with the Roman Catholic faith. The Augsburg Confession was read at that diet in Augsburg on June 25th, 1530. Chancellor *Beyer and John the Elector of Saxony read it out loud in front of the Emperor Charles V and all the other delegates that were present. It is said, and we don't know whether this is true, that Charles V was bored and fell asleep for the two hours when the Augsburg Confession was read. The response was mostly and predominantly negative. It seems that the Emperor Charles V already had an agenda when he came to the Augsburg Diet, and that was to listen to the cause of the Lutherans, but not to change his mind that he was not willing to condone a different theology in one of his countries and his lands. And so it seems that the hope that the Lutherans had coming to the Augsburg diet; namely, that they were going to present their cause and that they would be treated as equal partners with the Roman Catholic delegates and that their truth would persuade Charles V because they would say nothing else than that what was said in scripture. And they hoped that their presentation of the Augsburg Confession, then, with persuade Charles V and all others. Officially, it was not approved and not accepted by Charles V. There is a lot of contrivance that happened behind the scenes, especially from the Roman Catholic delegates. They were asked by Charles V to present a response to the Augsburg Confession. *Johann Eck and other leading theologians of the Roman Catholic delegation immediately set about to write a response that is called the *Confutatio. It was read aloud in front of Charles V. He, too, found it very boring and very redundant and far too long. And it did not address the real situation of Lutheranism. So the *Confutatio was not printed for a very, very long time precisely because Charles V, though he wanted to further the Roman Catholic Church, did not really accept the *Confutatio in its entirety. Melanchthon had never received a copy of the *Confutatio so it was not possible for him to review what was being said therein. But we know that certain notes were taken, handwritten notes, by those theologians that were present. So it was possible for him to review those, and upon that, had written the Apology of the Augsburg Confession. Unfortunately, Charles V was no longer to give the Lutherans another hearing, in other words, to listen again to the Apology. And so the hopes of Lutherans to be accepted by Charles V were dashed. They all left the Augsburg Confession – they all left the Augsburg Diet back to the regions from which they came. Thereby, we have to consider June 1530 perhaps a watershed period in that it now defined Lutheranism. I think we can now speak of a Lutheran Church, whereas before and during Augsburg, they still hoped of being a movement within the Roman Catholic Church, hoping that they could reform it. But as things seem now, they had to accept the fact that they were now becoming a separate movement of the Roman Catholic Church.