a first look at macroeconomics 1 Chapter 20 A first look at

advertisement

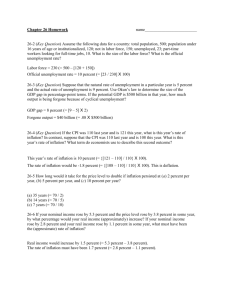

C h a p t e r 2 0 A f i r s t l o o k a t * macroeconomics I. Origins and Issues of Macroeconomics A. Modern macroeconomics emerged during the Great Depression (1929-1939) a decade of high unemployment and stagnant production throughout the world economy. B. Short-Term Versus Long-Term Goals 1. With high unemployment during the Great Depression, the initial focus of macroeconomics was on the short term. 2. During the 1970s, inflation increased and economic growth slowed, shifting the focus of macroeconomics to the long term. C. The Road Ahead 1. During the 1990s, as information technologies further shrank the globe, the international dimension of macroeconomics became more prominent. 2. Modern macroeconomics is a broad subject that studies long-term economic growth, unemployment, inflation, the government budget deficit, and the U.S. international deficit. II. Economic Growth and Fluctuations A. Economic growth is the expansion of the economy’s production possibilities. * 1. We measure economic growth by the increase in real gross domestic product. 2. Real gross domestic product (also called real GDP) is the value of the total production of all the nation’s farms, factories, shops, and offices measured in the prices of a single year, currently 2000. * This is Chapter 20 in Economics. 78 CHAPTER 4 B. Economic Growth in the United States 1. Figure 4.1 shows real GDP in the United States since 1962. 2. Potential GDP is the real GDP that the nation produces when all the economy’s labor, capital, land, and entrepreneurial ability are fully employed. a) Figure 4.1 shows that there is persistent growth in potential GDP. The long-term rate of economic growth is measured by growth in potential GDP. b) Potential GDP grew more rapidly in the 1960s than in the 1970s and early 1980s. The slow growth during the 1970s and early 1980s reflected the productivity growth slowdown. The growth rate of potential GDP increased during the 1980s and 1990s. 3. Real GDP fluctuates around potential GDP in a business cycle. a) A business cycle is the periodic but irregular up-and-down movement in production. b) A business cycle has two turning points, a peak and a trough, and two phases, recession and expansion. i) A peak is the upper turning point, the end of an expansion and the beginning of a recession. ii) A trough is the lower turning point, the end of a recession and the start of an expansion. iii) A recession is commonly defined as a period during which real GDP decreases for at least two successive quarters. iv) An expansion is the period during which real GDP increases. A FIRST LOOK AT MACROECONOMICS 79 4. Figure 4.2 shows the most recent U.S. business cycle, including the most recent recession in 2001. 5. Recessions in recent years have been much less severe than the Great Depression. C. Economic Growth around the World 1. U.S. real GDP growth fluctuates much more than the growth rate of real GDP in the rest of the world as a whole. 2. Among advanced economies, since 1992 Japan has grown the slowest and the newly industrialized economies have grown the fastest. Among the developing economies, the most rapid growth has occurred in Asia and the slowest growth has occurred in Africa and the Western Hemisphere. 3. The U.S. share of world real GDP is almost constant and is about 21 percent, but some fast growing nations such as China have gone from 4 percent in 1982 to 13 percent in 2002. D. The Lucas Wedge and the Okun Gap 1. The Lucas wedge is the accumulated loss of output that results from a slowdown in the growth rate of real GDP per person. Since 1970, the Lucas wedge has amounted to a staggering $50 trillion. 2. The Okun gap is the gap between real GDP and potential GDP. Since 1970, it has amounted to an estimated $2.7 trillion. 80 CHAPTER 4 3. Figure 4.5 shows the Lucas wedge and the Okun Gap. E. Benefits and Costs of Economic Growth 1. The main cost of fast growth is foregone current consumption. 2. Two other possible costs are more rapid depletion of exhaustible natural resources and/or more pollution, although technological advances that bring economic growth help economize on natural resources and clean up the environment. III. Jobs and Unemployment A. Jobs 1. In 2003, 137 million people in the United States had jobs—17 million more than in 1993 and 37 million more than in 1983. 2. The pace of job creation fluctuates with the business cycle. During the 2001 recession, 2 million jobs disappeared. During the expansion of the 1990s, 2 million jobs were created each year. 3. Most new jobs are in the services industries and are, on the average, higher paying than the ones lost. B. Unemployment 1. On any one day in a normal or average year, in the United States 7 million people are unemployed. 2. The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people expressed as a percentage of all the people who have jobs or are looking for one. The unemployment rate is not a perfect measure of the underutilization o f labor for two main reasons: a) It excludes people who are so discouraged that they’ve given up the effort to find work. b) Part-time workers, who desire full-time work but cannot find it, are not counted as unemployed. C. Unemployment in the United States 1. The unemployment rate reached a peak during the Great Depression in the early 1930s. It has been high, but not nearly as high, during recessions in recent years. 2. Figure 4.6 shows the unemployment rate in the United States from 1929 through 2003. A FIRST LOOK AT MACROECONOMICS 81 D. Unemployment Around the World 1. Since 1983, the unemployment rate has been generally higher in the United States than in Japan, but higher still in Canada and Western Europe. Business cycle fluctuations in unemployment occurred at similar times in the United States and Canada, but were out of phase when compared to Western Europe. 2. Figure 4.7 shows the unemployment rate in the United States, Canada, Western Europe, and Japan. E. Why Unemployment Is a Problem 1. Unemployment represents lost production and income. 2. Prolonged unemployment can cause lost human capital, which seriously hurts the person’s future job prospects. 82 CHAPTER 4 IV. Inflation A. Inflation is a process of rising prices. The average level of prices is called the price level, and the inflation rate is measured as the percentage change in the price level. A common measure of the price level is the Consumer Price Index (CPI). B. Inflation in the United States 1. Figure 4.8 shows the U.S. inflation rate from 1963 through 2003. 2. In the early 1960s the U.S. inflation rate was low; it reached its highest levels in 1974 and 1980. Inflation then decreased during the 1980s and has stayed relatively low in the 1990s. 3. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate is negative so that the price level is falling. A FIRST LOOK AT MACROECONOMICS 83 C. Inflation Around the World 1. Figure 4.9 shows inflation around the world since 1983. 2. Other industrial countries shared the same pattern of inflation as the United States. Developing countries have displayed much higher rates of inflation, although inflation has dropped closer to the levels of industrial countries in recent years. D. Is Inflation a Problem? 1. Unanticipated changes in the value of money mean that the amounts actually paid and received vary unpredictably. 2. People use resources to predict the inflation rate rather than to produce additional goods and services. 3. At high inflation rates money loses value very quickly; therefore people try to spend their money more rapidly. In the extreme case of a hyperinflation — defined as an inflation rate that exceeds 50 percent per month — inflation brings economic chaos and social disruption. 4. Getting rid of inflation is costly in terms of higher unemployment, although most economists believe this cost is temporary. V. Surpluses and Deficits A. Government and Budget Surplus and Deficit 1. The federal government has a government budget surplus if it collects more in taxes than it spends. 2. The federal government has a government budget deficit if it spends more than it collects in taxes. 3. Figure 4.10(a) shows the federal government and total government budget surplus and deficit measured as a percentage of GDP since 1962. 84 CHAPTER 4 4. Since 1970, the government has had a budget surplus from 1998 to 2000 and a budget deficit in the other years. As a fraction of GDP, the budget deficit was highest in the 1980s. B. International Deficit 1. The value of the goods and services sold to other countries (exports) plus net interest receipts minus the value of the goods and services purchased from other countries (imports) is the current account balance. 2. Figure 4.10(b) shows the history of the U.S. current account balance from 1962 to 2002. 3. Until 1982, the United States generally had a current account surplus; that is, it sold more to the rest of the world than it purchased. From 1982 to 1987, the current account deficit became large. It then decreased significantly between 1988 and 1991, after which it has increased once more and is currently near 5 percent of GDP. C. Do Deficits Matter? 1. Deficits can be harmful if the borrowing is used to buy consumption goods rather than more investment. VI. Macroeconomic Policy Challenges and Tools A. Until the development of modern macroeconomics, it was widely believed that the only economic role for government was to enforce property rights. B. Policy Challenges and Tools 1. There are now five widely agreed challenges for macroeconomic policy: a) Boost economic growth b) Keep inflation low c) Stabilize the business cycle d) Reduce unemployment A FIRST LOOK AT MACROECONOMICS e) 85 Reduce government and international deficits 2. Making changes in tax rates and government spending programs is called fiscal policy. 3. Changing interest rates and the amount of money in the economy is called monetary policy. The Federal Reserve (Fed) is in charge of monetary policy.