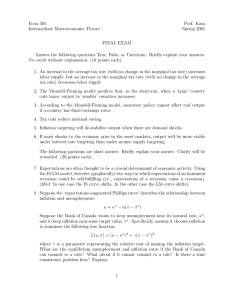

Output Gaps - An alternative measure of excess or deficient demand

advertisement

Output Gaps An alternative measure of excess or deficient demand If the economy grows, how fast and for how long can it grow before it runs into inflationary problems? What level of growth might be sustainable over the longer term? To answer this question, economists have developed the concept of ‘output gaps'. The output gap is the difference between actual output and sustainable output. Sustainable output i is the level of output corresponding to stable inflation. If output is below this level (the gap is negative), there will be a deficiency of demand and hence demanddeficient unemployment, but a fall in inflation. If output is above this level (the gap is positive), there will be excess demand and a rise in inflation. Generally, output will be below this level in a recession and above it in a boom. In other words, output gaps follow the course of the business cycle. The diagram shows output gaps for four countries from 1980 to 2005. As you can see, there has been a large positive output gap in Australia since the mid-1990s. This corresponds to a rapid rise in output and a fall in unemployment. You will also see that, until very recently, there has been a large negative output gap in Japan since the late 1990s. This corresponds to a deep recession, high unemployment and inflation just below zero (i.e. a slight decline in prices). Over the long term, the rate of economic growth will be approximately the same as the rate of growth of sustainable output. In other words, over the years, the average output gap will tend towards zero. But how do we measure the output gap? There are two possible methods. Measuring trend growth The simplest way of calculating the output gap is by measuring the trend growth rate of the economy (i.e. the average growth rate over the course of the business cycle: see Figure 10.2 on page 225) and then seeing how much actual output differs from trend output. The assumption here is that the sustainable level of output grows steadily. This is, in fact, a major weakness of this method. Technological innovations tend to come in waves, generating surges in an economy's sustainable output. Rates of innovation, in turn, depend upon how flexible the economy is in adapting to such new technologies and how much investment takes place in equipment using this technology and in training labour in the necessary skills. Business surveys An alternative way to measure the output gap is to ask businesses directly. However, such survey-based evidence can provide only a broad guide to rates of capacity utilisation and whether there is deficient or excess demand. Survey evidence tends to focus on specific sectors, which might, or might not, be indicative of the capacity position of the economy as a whole. So firms might be running above normal capacity (e.g. by overtime working) in one sector of the economy, while firms in another sector might have plenty of spare capacity to continue expansion. Thus survey evidence may give an incomplete picture of overall capacity utilisation in the economy. Question Under what circumstances would sustainable output (i.e.a zero output gap) move further away from the potential output ceiling shown in Figure 10.2 on page 225? The level of sustainable output is sometimes referred to as the level of ‘potential output'. This, however, is confusing, as the term ‘potential output' is used elsewhere (including this book) to refer to full-capacity output. Full-capacity output, however, would not normally be sustainable over the longer term because of the upward pressure on inflation caused by various bottlenecks in the economy. Thus sustainable output is below the level of potential output in the sense that we are using the term ‘potential output'. i