bon ami story - Hartford Courant Blogs

advertisement

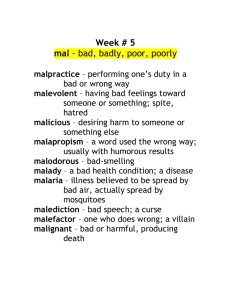

SCRATCHING THE SURFACE OF BON AMI'S BEGINNINGS By DAVID RHINELANDER Friday, August 27, 1999 (Note correction at end of story) John T. Robertson's relocation from Glastonbury to Manchester in the mid-1880s was the Silk City's gain and a bonanza for the world -- at least as far as fulfilling the desire for Bon Ami cleanser. But the move would never have happened if James B. Williams hadn't gone the other way 40 years earlier, abandoning Manchester for Glastonbury to launch his equally renowned Williams Shaving Soap business. Robertson, born in Glastonbury in 1856, rose to the rank of plant superintendent of the Williams soap works in the early 1880s. At the same time, he was experimenting on his kitchen stove with ways to make a better polishing soap than the Williams products, which used finely ground quartz as their abrasive. J.T. couldn't get J.B. to accept his advice to use a milder soap and softer feldspar in the cleanser. So Robertson resigned in a huff and set up the J.T. Robertson Soap Co. in an old, idle, water-powered mill in the north end of Manchester owned by the Childs family. He started with five workers making his own product, which he called Brightness. The soft mineral soap, made only in cake form at first, was soon renamed Bon Ami, which means ``good friend'' in French. The name caused a bit of trouble at first because few people knew how to pronounce the French (bon-ah-me), and grocery stores had trouble figuring out what people wanted when some asked for ``bon amy'' and others insisted on ``bone am eye'' or ``bone a me'' or something else. Pronunciation problems notwithstanding, the product became a success. Manchester's William H. Childs and his rich New York cousin, William H.H. Childs, liked what they saw and in 1890 set up the New York firm of Childs and Childs as Bon Ami's exclusive sales agent. The Bon Ami Co. was created in New York City as the holding company and distributing agent. A third entity, the Orford Soap Co., became the manufacturing arm. Orford Parish was Manchester's original 18th century name. The old Childs mill burned in 1899. Robertson moved into a large, handsome Romanesque brick factory nearby that featured high windows and twin towers in front. That building originally housed the Mather Electric Co., founded by two members of the Cheney silk-making clan. The Mather Co., after a strong initial start making electric motors and light bulbs, collapsed after it lost two patent infringement suits to Thomas Edison. The Childs cousins understood the value of vigorous promotion. The yellow chick on the label and the slogan ``Hasn't Scratched Yet!'' became textbook examples of using a distinctive trademark and a powerful advertising campaign. Why the little yellow bird? A newly hatched chick still has its nourishment from the egg yolk and will not scratch the ground for food for several days after it emerges from its shell. Bon Ami's feldspar abrasive didn't scratch wood, glass or metal or anything else it was applied to. The double meaning was appreciated immediately. Swarms of local boys were hired all across the United States and Canada to promote Bon Ami. The sampling gang, as they were called, were issued leather bags filled with cakes of the soap. They went door to door giving away the 10-cent bars. The local grocers were then told that everyone in town was using Bon Ami and that they had better stock up. The ploy worked. Sales soared. The Hilliard Street factory expanded. Its payroll topped 150 workers in 1903 and the enterprise was valued at $3.5 million. The product line expanded to include the powdered form of Bon Ami, which today is the nation's third most-popular canned cleanser. At one time, a special blue-tinted bicycle cleaner was put on the market at two or three times the price of a can of regular Bon Ami. The only difference was the tiny amount of blue dye mixed in. Advertising was relentless. For the 1908 dedication parade of the Bulkeley Bridge between Hartford and East Hartford, the sides of a horse-drawn wagon were made to look like a giant cake of Bon Ami soap. An employee dressed in a chick costume waved from the driver's seat. By then, beautiful full-page color ads were appearing regularly in The Ladies Home Journal and other magazines. One showed a young girl wiping down a bathtub: ``Look Mom, anybody'd think this was a new tub,'' proclaimed the headline. Others showed housewives cleaning windows or pots and pans or woodwork or mirrors. ``A housekeeper who uses it once will want it always,'' said another headline. Production problems began to cut into the firm's profit margin in the 1920s. The factory built its own equipment to make fiber containers for powdered Bon Ami and to load the cans, but the old factory building was inefficient. Worse, making the cakes of soap remained particularly difficult and timeconsuming. Each had to be air dried for 30 days so it would not crack or crumble. Bon Ami continued in the hands of the Childs family for decades. Shares were then put on the New York Stock Exchange, with the Childses maintaining majority control and reaping millions of dollars in profits. But the third generation of the family finally decided to diversify their holdings and sold Bon Ami in 1954. The firm changed hands several more times in the decade. Promotion and advertising expenses were cut back. Sales fell. Calamity struck in 1959, just as the firm was preparing its 75th anniversary celebration. First the Securities and Exchange Commission desisted the stock, claiming its profits margins were too small and that a chairman, Alexander L. Guterma, had milked the company of as much as $500,000. Guterma ended up in jail with several colleagues because of several illegal transactions. The Manchester plant, which was down to 70 employees, closed on Oct. 31, 1959, amid reports of a projected $375,000 loss. The plant and equipment, the owners said, were hopelessly out of date. Bon Ami continued to be made under contract in Los Angeles, Chicago and Newark, N.J. The firm changed hands several more times and barely limped along until the Faultless Starch Co. of Kansas City, Mo., a privately held company, rescued it in 1971. The newly formed Faultless Starch/Bon Ami Co. soon launched a massive national advertising campaign. ``Never underestimate the cleaning power of a 94-yearold chick with a French name,'' said a 1980 ad. Sales have taken off again and Gordon T. Beaham III, current chairman and greatgrandson of the founder, Maj. Thomas G. Beaham, made a pilgrimage to Manchester recently to celebrate the renaissance of the scratchless chick. Correction: Correction was published on 09/24/99./ When John T. Robertson left the J.B. Williams Soap company in Glastonbury and moved to Manchester to make his own cleanser, he named his soap cakes Robertson's Mineral Soap. It was that product that later was named Bon Ami. The Williams company continued to make its own cleanser, Brightness. Brightness never became very popular. Bon Ami, which was made in Manchester for 75 years, was a huge success and continues to sell well today.