Voices from the Hills: Gaelic Culture & Heritage

advertisement

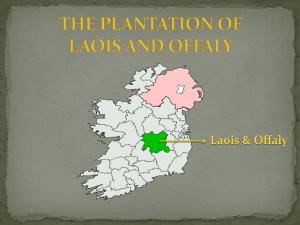

FROM THE BOOK Of KELLS, (CIRCA 600-900). (THE

BOOK OF COLUM CILLE.)

Voices from the Hills.

(Guthan o na Beanntaibh).

A Memento of the Gaelic Rally,

I927.

Edited by

John MacDonald, M.A.

position of abiding pre-eminence amongst the illuminated manuscripts of

the world."—Sir Edward Sullivan, Bart.

Its Weird and commanding beauty . . . the unwearied and

patient labour that brought it into being . . . have raised it to a

Published by

An Comunn Gàidhealach (The Highland Association).

Glasgow.

1927.

l\iuj permission t i j " The Slmlio.

Poets IUIU heroes are of the same race; the latter do what the former conceive.

—Lamartim..

O

Cl a n na na n Gaid h ea l r i g ua il lib h a c hei le.

VER fifty years ago, Professor Blackie published his inspiring

dissertation on "The Language and Literature of the Scottish

Highlands." Tomes have been written on the same fascinating

subjects since. To rouse his countrymen from the " deep slumber of

decided opinions " was the work of this robust sponsor of our ethics.

But while he found not a few who were " Highlanders in their core as

in their kilt," the general attitude was more in the way of sentimental

sympathy than practical aid. He, however, succeeded in his aim; and

the Celtic chair in Edinburgh is an enduring monument to his

enthusiastic and scholarly pleading of our cause.

Nevertheless, a change was in progress. Whitley Stokes, an

Englishman, had already established his fame as a Celtic scholar, while

his translation of the " Voyage of Maelduin " marked an epoch in

classic literature. Matthew Arnold, with less benignity but greater

force, created a receptive atmosphere in England —the England which,

according to Richard Green, would not have produced its Shakespeare,

but for the quickening infusion into its veins of the blood of Ossian's

race—and enlightened Oxford, in consequence, gave us our first chair

of Celtic. This event, indeed, may be said to be the academic a c c o l a d e

of the Gaelic Renaissance. The " I am!" of Taliessen ( T i l l i d h O i s e a n ,

perhaps), together with his "I have been!" is now demonstrated to an

astonished and admiring world by the Zimmers, Zeusses,

Kuno-Meyers, Alfred Nutts, and others similarly gifted, who have

engaged in Celtic research, and who have discovered and are discovering the " hidden and precarious genius" of the Celtic families to

be amongst the most attractive of studies.

The hope of An Comunn is, that " Voices from the Hills " may

come within hearing of all Gaeldom. Equally so is it their wish to

acknowledge with gratitude the loyal and disinterested services of Mr.

John MacDonald in preparing this book, as well as in having assisted

in the preparation of Gaelic text-books for our schools. He has, with

fine discrimination, "chosen his authors as he would his friends." As

the result of his labours—and I am writing

more with the fresh gaze of a child than as a

qualified critic—we have this volume of rich

and varied thoughts on matters Gaelic.

Besides taste, he has given proof of rare tact in having persuaded

so many friends to advocate the claims of our Association. The

following pages are, therefore, occupied by many helpers who, though

not immediately of the blood, have joined the children of melody, and

are thereby purified through initiation. " Voices from the Hills" is, in

every respect, a notable book, and p e n t e c o s t a l in its import. The

student and the casual reader alike will find it an illuminative

companion. To me it suggests the magic lights of a cairngorm in a

bard's chaplet—a fragrant censer to the Celtic soul, a votive tablet in

the Hall of Shells.

So be it. Welcome is the appreciative spirit that casts its prophetic

eyes over our beautiful heritage and the still surviving language of our

people. Gaelic, which has enshrined the voices of unrecorded centuries,

speaks with authority to her children, as the voice of a mother, which

they know. Like Cuchullin's rebirth, it is now being nourished on the

lap of protecting foster-gods. And, when the quickening current has

charged the ethereal circuit, the soul of the Gaelic hero, chanting a

refrain, will appear once again to the " fifty queens " who loved him;

they will understand the ge n r e of his mystic song. We shall then join

with Emerson in saying that " the Celts are an old family of whose

beginnings there is no memory, and their end is likely to be still more

remote in the future . . . "

It is true that the waves of enthusiastic raptures which greeted the

advent of MacPherson's O s s i a n have somewhat subsided; but the

V o y a g e o f B r a n —chronologically anterior in order of redaction—disclosed a key to other deeper and more alluring mysteries. And

from the argosies of Tir-nan-Og—that " Isle which spreads large to the

sun like a beautiful dream of the soul" —seeds, in which lie immortal

blossoms of loveliest form and hue, have fallen upon many a fallow

genius. T h e L a n d o f t h e L i v i n g H e a r t —perhaps the most beautiful

creation that ever left a poet's loom—is charted anew for the sons of

remembrance. " Why is Art, A o n - f h e a r —The Lone One—named so till

the Judgment?" is no longer a cry of sorrow to Coran, the Druid. A

more enchanting trilogy is being intoned by the Birds of Rhiannon. The

gleaming c u r a c h , with Fate at the helm and Love at the prow, is

majestically bearing its soul-freights to the Isle of the Ever-living

Living—the Happy Otherworld of the Celt, which lies in serene

composure between the two eternities.

ANGUS ROBERTSON, President of

\n Comunn Gàidhealach.

Editor's Foreword.

O

N behalf of An Comunn Gàidhealach, I tender warmest thanks to

each and all of those who have enabled us to make this record of

"Voices from the Hills," voices old, yet ever new, as the cry of the

sea, the cry of the wind, the cry of the curlew, or the cry of man's spirit;

they are the voices of those who view from the heights a land of

promise for the Gael, if he but march on, go in, and take possession.

Personally, I thank the contributors for their kind, encouraging letters.

Indeed, were I able to focus to a narrow compass the correspondence,

apart from the articles in the book, it would make the most inspiring

article of all, and would give An Comunn confidence that there is no

lack of friendly feeling throughout the land, and thus give it renewed

energy to go forward with unfaltering step.

Furthermore, one received the distinct impression that An Comunn

may not have fully realised all the latent forces that may still be

mobilised for the furtherance of their Cause. When the compilation was

begun, for various reasons, it moved somewhat slowly, but as time went

on, more and more eager and devoted helpers came forward with pen

and brush. Indeed, towards the close of the work, one wished that the

end had somehow been the beginning, as one felt as proud as Roderick

Dubh, when he whistled shrill, and

" Instant, through copse and heath arose,

Bonnets, and spears, and bended bows."

Any lengthy, elaborate " introduction " to the book might prove to

be but wasteful and ridiculous excess, all that is really necessary being

to introduce to readers (may we hope for hosts of them!) the gifted and

leal-hearted friends of the Gael who so willingly responded to an

invitation to take part in, what may be called, a symposium on the

1

present position of all that affects the welfare of Gaeldom, and on the

responsibility which every true Gael should feel and accept, with his

whole heart and mind, with regard to it, unless he is resigned to looking

on (if he looks at al!) in helpless inaction, while the most precious gifts

from our heroic past are being borne away by the stream of modern

life, which may too jauntily be called " Progress." viii. Editor's

Foreword.

According to a brilliant American sociologist, the only relevant

question in considering the reality of human progress is, " Have we

evidence of a richer and more profound human experience?" —and to

this question he gives a direct negative, adding that society must now

realise that true progress is to be measured in terms of " significant

persons." This view alone is a sufficient r a t s o n d 'etre for the work of

An Comunn in its own special sphere. Some of us are strongly of

opinion that, within our own memory, there has been in our Gaeldom a

steady decrease in the production of " significant persons," and we

believe that the decrease is in proportion to the decay of the expressive

and soulful old language, and of the traditions of romance and heroism

and of antique virtue and faith it enshrined. It is to be feared that the

"Christopher" type of character is becoming rarer in the Highlands.

Without taking the extreme view of those who write and talk

seriously of " Civilization—its cause, and cure," one may find ground

to be apprehensive as to what shape our civilization may take if some

of the modern modes of thought lead us into the hallucination that the

way to advance is to make a clean break with the past, so that we turn a

deaf ear to the great voices that echo < through the corridors of time,'

and we treat as a thing outworn the spiritual attitude towards life of our

wise and brave forefathers, who brought us where we are in the upward

climb. Our belief is that our British, as well as our Scottish, civilization

can have no more cleansing and elevating influence acting upon it than

that of the spirit and the culture of the Gael We answer to the roll-call

of more than one citizenship, and acute observers in lands overseas

remark on the beneficent effect of Gaelic influence on Colonial life. In

a notable manifesto recently issued by a Society in the Republic of the

West, eloquent expression is given to a deep sense of debt to those of

our race who took part in the founding and making of that great

country. Like the leaven that the woman took and hid in the meal, their

genius, both literary and spiritual, has worked potently, and on a

historic scale, and will continue to do so, unless it is allowed to become

extinct.

We are not greatly ruffled by the taunt that we are out of step with,

or lagging far behind the march of modern thought, that we are unable

to understand we are living in a changed world. We are quite awake,

and never dream of clothing ourselves again in all the outward vesture

of the thought and life of

IX.

Editor's Foreword.

our ancestors, though who would not say that much of it was more

picturesque and had far more meaning than that of our contemporaries?

Who would contend that the various forms of Highland dancing, even

on the rough, clay floor of a barn, were not a far more graceful and

dignified expression of the spirit of innocent merriment than the

grotesque wriggling to be seen nowadays in a modern p a l a i s d e dans e?

And a straw shows how the current goes! Or, to use a homely simile,

may we not wish that a spinning-wheel, and song, and love and worship

shall still be found in a Highland cottage, without demanding of the

Legislature that it shall be thatched with the old time bent, bracken or

heather, instead of the slate of these days? We believe that the

chivalries, the loyalties, the hospitalities, and the spiritual values of our

forefathers are not so very incompatible with the law of change.

Our contributors, besides entertaining us with song and story, have

articulated clearly and convincingly the mind and purpose of An

Comunn, and given many wise suggestions as to how best to deal with

the whole Gaelic question; but "so many men, so many opinions." We

do not expect, nor might it be well, that our readers should agree with

all the views expressed in these pages. Our case, however, is in no

danger from free, well-meant discussion, which, at least, serves to show

that there is a live, active interest being taken in it, so that, like the

ardent lover, we say, " Speak well oJ my love, speak ill o' my love, only

aye be speaking!" In a page here and there one may hear a hint of the

approaching decease of the Gaelic language, but even then the writer

seems to turn an attentive ear to the strange, rich harmonies of the dying

man's tongue. With regard to what may seem more severe criticism, let

us remember that " A good horse may be forgiven a kick." We need not

fear differences of opinion among our friends, so long as beneath there

is evidence of mutual understanding on vital points.

Something like alarm is expressed as to the rapidly diminishing

number of Gaelic speakers throughout Scotland, and especially within

the Gaelic area, as shown by each succeeding Census, but this

admittedly disquieting fact should only rouse An Comunn to more

vigorous activity, and the fact that we can count moral gains that

outweigh numerical losses should be a spur to more determined effort.

Leading statesmen who hold that character,

1

X.

Editor's Foreword.

rather than material wealth, is the real source of" the strength or" a

people, regard our work as supremely important national service.

Although the 1921 Census shows a decline'in Gaelic that is serious

enough, it is not likely that a Registrar-General would comment upon it

now, as did the gentleman of the 1871 Census, when he wrote:—"The

Gaelic language stands in the way of the success of the natives in life; it

shuts them up from the paths open to their fellow-countrymen who

speak the English tongue." We might try to find a half truth in his

statement had he not gone on, " We are o n e people, we should have but

o n e language," and, to crown the absurdity, he might have added that

we should be of o n e mind, and cast i n o n e mould. We who think that

the confusion of tongues at Babel became a powerful factor in the

evolution process, rejoice in the " Braid Scots " movement of our time,

and wish it all success.

In recent years, increasing numbers of Gaelic students have passed

through the Celtic classes in our Universities, and through the higher

classes in our Secondary Schools, and it is certain that the effect of

higher education of the right kind will be to make these students set, not

less, but far higher value on their mother-tongue, so that we may look

for an intellectual factor working more and more in the Gaelic

Movement, and greatly reinforcing it. The Registrar-General of 1871

proposed that "Gaelic should cease to be taught in all our national

schools." How changed the scene in the Education (Scotland) Act of

1918, in which we read that " Local Authorities are required to include

in their educational schemes adequate facilities for teaching Gaelic in

Gaelic-speaking areas "—still a wide field, and now an open field for

action, if only the v o x p o pu l i declares that it is the wi l l of our people

Editor's Foreword.

XL

that the Gaelic Clause should become fully operative in all the schools

of Gaeldom, and that it is their resolve that their race shall not perish

from the earth, and that the land in which it was wont to be bred, and

the language by which its spirit was wont to be nurtured shall be

preserved at all costs.

We would make an earnest appeal to all patriotic ministers and

teachers to assist in making this Gaelic Rally of 1927 memorable and

lasting in its effects, by joining the membership of the Association, and

becoming co-workers in a great cause. By precept and example, they

would help greatly in forming, and in setting in motion that force of

public opinion which is essential to the success of a Gaelic

Renaissance. We would, however, do well to keep in mind that the

rise or fall of our hopes and aims should not be allowed to depend on

mere numbers. In connection with the Bohemian movement for the

freedom of the race spirit, it is told that at one stage the work was in

the hands of a small group of scholars, who were writing in their native

Czech, trying to awaken the spirit of their countrymen by calling their

attention to their music, literature and history. So small was this band

of patriots, through whose work a nation was ere long to be reborn, that

one of them remarked at their little meeting, " If the ceiling of this

room were to fall and crush us, there would be an end of our National

movement."

Our Association is not exclusive, as we know many who have

community of spirit with us, though their name or tongue may not

show a direct Gaelic connection. They give us material, as well as

moral support, so we cordially invite them into full fellowship, and will

be proud to enter their names on our roll without applying any < Mac 5

or ' Shibboleth ' test. We also think that it would conduce to the creating

of a lively race consciousness to cultivate fraternal relations with other

peoples who claim race kinship, and show spiritual affinity with us, and

expressly seek union with us. In a commonwealth of Bretons, Welsh,

and Scottish and Irish Gaels there would be generated a high-temperature enthusiasm which would react on each group. In the literature,

both past and present, of these kindred peoples, and in their traditions

and history, there is always, apart from their universal interest, a note

that strikes a responsive chord in the breast of every Gael.

While our main objective is the preserving and perpetuating of all

in language, literature and music, that goes to the making up of a Gaelic

culture, one cannot help thinking that some prac tical interest in

questions vitally affecting the material welfare of Gaeldom might well

come within the ambit of An Comunn's operations. We might make

good use of the secret of the wonderful race consciousness of the Jews,

who are willing to make any sacrifice to have their ancient p a t r i a

restored, so that they may have a " homeland " to which their hearts

may ever turn, though their eyes should never behold it. We shall have

no Gaelic if the Highlands become "the silent hills of the vanished

races," no songs when the songsters have all flown, no Gaels when " the

nursery is emptied of its children."

Long live and flourish our Mods, but, though the walls of

xii.

Editor's Foreword.

Thebes rose to the music or* Amphion's lyre, the heroic young patriot,

Nehemiah, took the practical way to rebuild the walls or" the dear city

of his fathers—" every man with one of his hands wrought in the work,

and with the other held a weapon." While we seek to have Gaelic taught

in our schools as part of a truly * liberal * education, it would be in line

with a re-peopling policy to lead our Highland children into finding

new meanings in the saying, " God made the country, and man made

the town." It is encouraging to know that educationists in England are

of opinion that " too little is being done to make agriculture attractive as

a vocation to country boys and girls."

It is hoped that this volume may be in some small way a memorial

of what is being done in 1927, A.D. to pass on the Gaelic heritage to

our children, and it is also hoped that such a Fund will be raised for An

Comunn's work as will be an impressive memorial that we are earnest

in deed as well as in word. This year 1927 may prove a decisive one as

to the future fortunes of Gaelic.

I tender to Mr. A. J. Sinclair, of the Celtic Press, my sincere thanks,

as this work was made much easier for a tyro editor by his unvarying

patience and courtesy.

An Comunn will also be glad to see grateful mention made of the

names of a few gentlemen who took a special interest in this

compilation. Mr. Robert Bain kindly gave free access to the treasures of

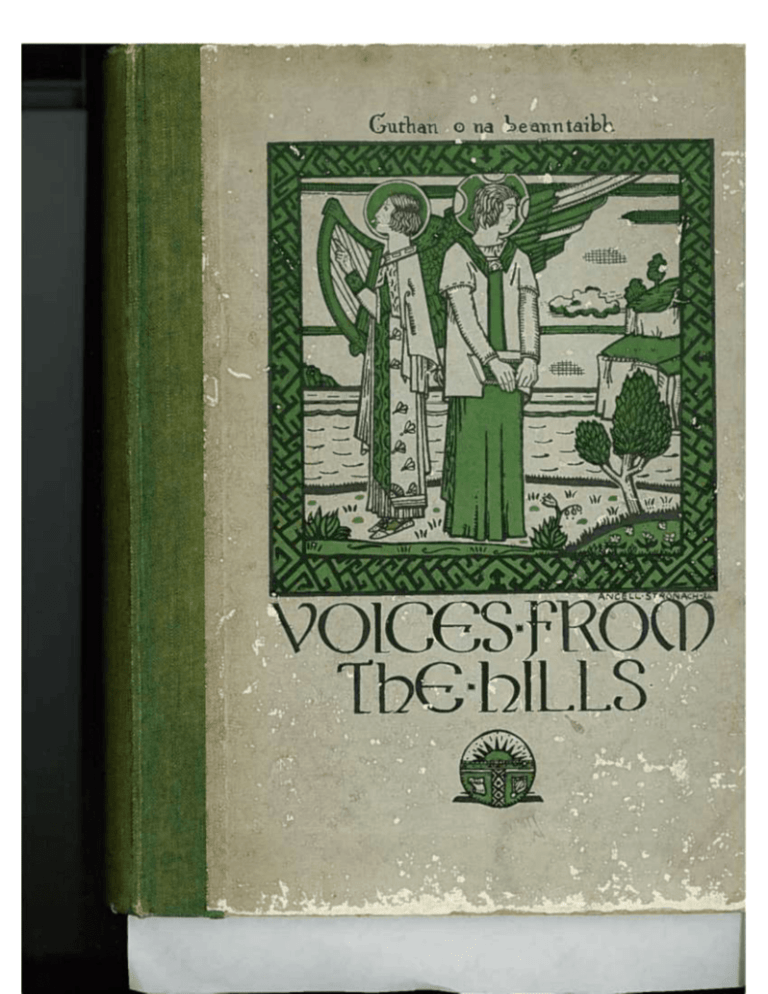

the Mitchell Library, which helped greatly in securing illustrations. Mr.

Ancell Stronach, of the Glasgow School of Art, generously undertook

the making of the Cover design, besides giving two striking examples

of his art. To Dr. Pittendrigh Macgillivray and to Mr. John Duncan I am

much indebted for having written me, time after time, with valuable

suggestions as to the illustrations. I wish to make reverent mention of

the name of Mr. James Cadenhead, who, in sending an exquisite hill

picture, wrote most kindly only a few days before he passed, to see, no

longer "through a glass, darkly," the beauty which, as was said of him,

was " ever the quest of his soul."

JOHN MACDONALD.

Contents,

PAG

E

V. President's Foreword.

vii.

Editor's Foreword.

i . Wild Hills,

................................

2. Is toigh leam a' Ghaidhealtachd,

3- Message from Principal Sir Donald

D.C.L., D.Sc., Ph.D.

4 The Fèill—its purpose,

6. Message from The Right Hon.

7- Message from The Right Hon.

8. Message from The Right Hon.

9- St. Columba's Influence on

Scottish History,

i i . Astray in Appin,

1

5-

*72324.

3»35383942.

49.

5355-

Tuireadh an Usaoidh,

Dealachadh nan Rathad,

Ossianic Poetry,

Carmina Gadelica,

Our Traditional Racial SongLore,

...

..................

Looking Northward, ...

The Reaper, ...

Our Irish Civilization,

Gillias, ...

Domhnull Ruadh a' Bhuinne,

The Golden Eagle,

A Highland Heroine for Highland Women,

Pittendrigh Macgillivray, R.S.A., LL.D.

Iain Caimbeul, Bàrd na Leadaig.

MacAlister, Bart., K.C.B." M.D., LL.D.,

Malcolm MacLeod.

Lord Alness, Lord Justice Clerk. David Lloyd

George M.P.

J. Ramsay MacDonald, M.P.

Rev. Prof. Main, D.Litt.. D.D.

Neil Mun ro, LL.D.

Iain Mac Cormaic, F.S.A. (Scot.)

Domhnall Mac-na-Ceardach.

Translated by Thomas Pattison.

John Duncan, R.S.A.

Marjory Kennedy-Frascr, C.B.E.

Compton Mackenzie.

IVilliam Wordsworth.

Alice Stopford Green.

Countess of Cromartie.

Donnchadh Mac Iain.

Seton Gordon, B.A. (Oxon), F.Z.S.

Augusta Lamont, B.Sc.

56- With Apologies to the True

Believer, ...

Bessie J. B. Mac Arthur.

59- The Importance of Highland

Folklore, ...

Donald A. Mackenzie.

64. Duanaire na Sracairc,

68.

6q.

76.

78.

80.

Is togarrach a dh' fbalbhainn,

The Return of Finn, ...

Tìr nam Beann,

The Gael in Scottish History,

What I think of the Gaelic

Movement,

Prof. William J. Watson, M.A., LL.D., D. Litt.,

Celt.

Domhnull MacLeoid, H.M.I.S.

John L. Kinloch, M.A.

Alasdair MacDhomhnaill, ("Gleannach").

Prof. Rait, C.B.E., LL.D.

William MacKay, LL.D.

8387.

91.

92.

9798.

Christopher,

Seann Sgeul mu Eilean Hirt, Oran a'

Phrionnsa, ...

A Maker of Modern Gaeldom.

Message from Wales,

The Gael and His Song,

Rev. Lauchlan Maclean Watt, D.D.

Iain N. MacLeoid.

Alasdair Mac Mhaighistir Alasdair.

Lachlan MacBean.

Rev. H. Elvet Lewis, M.A.

Robert MacLeod, Mus. Bac, F.R.C.O.

Contents —continued.

XIV.

FACE An Dìleab,

T

rtrt

1 UVi

IOL

104.

106.

108.

Highlanders All,

.....................

To a Highland Girl, ...........................

The Life of a Crofter,

Rev. A. Boyd Scott, M.C., D.D. William

Wordsworth.

Alastair Cameron.

Bàrdachd Spioradail na Gàidhealtachd, -■■

An t-Urr. D. Mac GiU'Eathain, D.D.

112.

Ruairidh Mòr,

....................

Fèill,

...............................

117. Highland Depopulation,

122. The Return of the Exiles, ...

125. The Red Deer, ........................

128. Am Fiadh,

129. The Study of Scottish Gaelic,

III.

The Celtic Spirit,

.......................

135- Love's Last Request,

Slàinte bho Thoileachas1 jU.

inntinn,

1-1S. Then and Now,

.....................

1

Seumas Mac Thomais, M.A.

JU.

146.

152-

The Assynt Maid's Lament, ...

Pàruig Mòr,

..................................

Message from Cornwall,

Na h-Ailleagain 's an Calman,

157- Sean Cheatharnaich Lochabair,

'59-1 Sheiling Girl's Song,

60.

The Departure, (A Dream), ■•

162. In Our Parish—The King's

Pensioner

16S. The Canadian Boat Song, ..

169. Tìr nan Og, (Land of the Ever-

Alasdair Alpin MacGregor.

An t-Urr. C. MacGill'Innein, D.D.

Rev. Murdo Lamont.

M. E. M. Donaldson.

Major John Ross, F.S.A. (Scot.)

Seumas Mac-an-Rothaich.

Prof. John Fraser, M.A. (Oxon.), LL.D.

William Power.

Colonel John MacGregor.

Alasdair MacDhomhnaill, ("Gleannach").

Sheriff MacMaster Campbell, C.B.E ,

F.S.A. (Scot.)

Pittendrigh Macgillivray, R.S.A., LL.D.

William D. Lamont, M.A. (Hons.) R. Morton

Nance.

Aonghas MacDhonnchaidh.

An t-Urr. D. A. Caimbeul, D-D.

Donald A. Mackenzie.

Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland.

Rev. Norman MacLean, D.D.

Anonymous.

Rev. Neil Ross, M.A., B.D. Murchadh Mac Ghille

Contents—continued.

Young),

... Na h-Eilthirich

175-1 Ghàidhealach,

77La Bretagnes et Les Celtes

Insulaires,

180. Highland Home Industries, ...

......................

184. Highland Pride,

>85. Gaelic in the Pulpit, ...........................

188. Taisbeanadh, ... Uilleam

190. MacDhunleibhe,

194. The Better Singer, .........................

195- The Song Battle,

........................

196.

The Song of the Blood,

197.

An Uiseag,

...................................

198. The Mòd,

................................

201. Differences between Gael and Ga

205. Sheiling Life in Lewis, The Call of the

209. Isles,

PAGE Seann Sgeul Gàidhealach,

...

2IO. Long nan Saighdearan,

213. The " Bothan " (The Highland

214. Cottage), .............................................

2l8. Crois-tàra (The Fiery Cross), Glasgow

226. Lassie's Visit to

228. CuUoden, ...

230. Mu Shòbhraig Oigh, ...........................

23.v

Ròs Aluinn,

241.

Notes on Celtic Place-Names,

245The Celtic Craftsmen,

248.

The Epithet " Celtic,"

252.

A Ghàidhlig anns na Sgoilean,

256.

Grianan,

257the

Imprisonment

of

261. On

xv.

Mhoire.

Le Docteur-Barde, M. Jaffrennou.

Mrs. W. J. Watson and Miss J. D. Bruce.

Lady MacAlister of Tarbert. Rev. John

MaeGilchrist, B.A., (Oxon.), D.D.

Iain Mac Cormaic, F.S.A. (Scot.) An t-Urr.

Gilleasbuig MacDhomhnaill, D.D.

Rev. Kenneth MacLeod. Rev. Kenneth MacLeod.

Rev. Kenneth MacLeod. Niall Mac Gille

Sheathanaich. U. M.

11, Prof. Douglas Hyde, LL.D., D.Litt. Norman

Morrison, D.ès. Sc., F.Z.S.

Bessie J. B. Mac Arthur.

Alasdair MacDhomhnaill, ("Gleannach"), lain

Mac Phàidein.

Colin Sinclair, M.A., F.R.LB.A. The Hon. R.

Erskine of Marr.

Catherine A. MacDonald. Catriona Ghrannd.

Domhnall Mac-na-Ceardach. Rev. Chas. M.

Roberston. Hugh Munro.

Prof. John Fraser, M.A. (Oxon.), LL.D. Daibhidh

Urchardainn, M.A. Seumas MacLeoid.

Prof. W. J. Watson, M.A., LL.D.,

D.Litt., Celt. Rev. David R. Williamson.

Alasdair Alpin MacGregor. Ludovic MacLellan

Mann, F.S.A. [Scot.) William Wordsworth. Alister

MacDonald, ("Gleannach. "ì I. MacDh.

Gun urrainn.

264.

264.

269.

270.

271.

278.

283.

285.

2S9.

290.

296.

Argyll,

.........................................

The Eagle in Captivity,

... ' A Tale

of Old Glen Strae, ... Druid Circles

and Rock Carvings, Sonnet to a Stone

Circle, The Seven Men of Glenmoriston,

Raonall MacDhomhnaill,

Obair-àrdair,

.............................

Cumha air Fear Obair-àrdair, Tobar

Nighean an Rìgh, Sir Cailean Caimbeul,

Marbhrann do'n Ridir Cailean

Caimbeul, ...........................................

An Old Highland Industry —

Kelp-Making, The Land of Heather,

Na h-Orduighean,

......................

The Gaelic Outlook, ...........................

The Heritage of the Gael, ...

298. Song of the Stag,

........................

299. Sandy to Alasdair,

........................

300. Litir

Fhionnlaigh

Phiobaire

g'a Mhnaoi,

...............................

Do Gaels of Canada place an extra

303.

value

upon

the

Gaelic-speaking

Immigrant,

304. Gaol Duthcha, ...

Eachann MacDhùghaill.

T. D. MacDhomhnaill.

Aonghas MacDhomhnaill.

Archd. N. Currie, M.A., D.Sc, A.LC. Donald A .

Mackenzie. Domhnall Mac-a-Phì. Prof. Magnus

MacLean, M.A., D.Sc, LL.D.

Right Hon. lan MacPherson, P.C., K.C.,

M. r\

Donald A . Mackenzie. John Buchan,

LL.D.

Bho'n " Teachdaire Gàidhealach.

Bertram W. Sinclair.

.4. Sinclair, ( A n Gàidheal, 1871).

1,

Illustrations.

Frontispiece,

...

Plate from the Book of Kells.

From " The Studio."

FACING

FACE

I. Sundown in Lome,

16. Burns and Highland Mary, ...

21. Columba and the Old Horse,

28. Dawn,—St. Martin's Cross,

lona,

53- The

Eaglet's

First

High

Venture, .......................

60. The Mermaid, ...

85- Autumn, Early Morning, Dugald

92. Buchanan's Cottage,

Sir D. Y. Cameron, R.A., R.S.A., LL.D.

Pittendrigh Macgillivray, R.S.A., LL.D.

John Duncan, R.S.A.

Archd. Kay, A.R.S.A., R.S.W.

Photo, by Seton Gordon, F.Z.S.

Ancell Stronach, Glas. School of Art.

James Cadenhead, R.S.A.

Photo, by Valentine & Co.

"3- Cup and Horn, Dunvegan, ...

128.

149.

149.

156.

177.

192.

197.

204.

213.

220.

The Home of the Red Deer,

Night Clouds in Mull,

Highlanders at Home,

Ancient Toward Castle,

A Heavy Sea at Staffa,

The Song of the Hill,

The Distant Hills,

The Road to the Glen,

Where Birches Wave,

The Valley of the Shadows,...

Culloden Moor,

....................

Photo, from Canon R. C. MacLeod o r

MacLeod.

V. R. Balfour-Browne.

Hugh Munro.

Photo, from Major John Ross.

Photo, by Sir N. Lamont, Bart.

Photo, by D. B. MacCulloch.

Photo, by John Baird, A.R.P.S.

Photo, by J. MacKissack, F.R.P.S.

Photo, bv J. MacKissack, F.R.P.S.

Photo, by John Baird, A.R.P.S.

Photo, by J. MacKissack, F.R.P.S.

Photo, by Valentine & Co.

240. Saint Bride.

261. Callanish Druid Circle, Lewis,

268. Shield and Sword,

{Glenmoriston),

Ancell Stronach, Glas. School of Art.

Photo, by Valentine & Co.

277.

284.

293300,

Harry W. Phillips.

Lockhart Boyle.

Photo, from " Glasgow Herald."

Photo, by D. B. MacCulloch.

Sir Colin Campbell—Lord Clyde

Cogadh na Sith, (Quatrc Bras)

Sentinels of Enchanted Land,

The Duart Lighthouse,

From William MacKay, LL.D.

-J

p

i

5

5

WILD HILLS.

'T'HE great, wild hills !—

Old thunder notes of earth:

Dominating, brooding,

Over some mystic birth:

O

d

u

<

u

z ce

o -J

z

zo

Q Z

D

a

Wind, and rain-swept heights;

Arid from fire, and ice-cap;

Haunts of Eagle and Deer

Where the forests be-lap:

Dour walls of basalt crag—

Lochs, silent and deep—

Shadowy glens remote,

Where the goblins keep:

Bracken-clad bosky dens

With chattering silver streams—

Nooks where the green fairies dance, With laughter

and little screams:

O wonderful wild hills!—

In the sun or the moon's light;

How you forever allure me

With your silent, secret might!

PITTENDRIGH MACGILLIVRAY.

Kind

permission oj

"Glasgow

Herald.1'

Is Toigh Leam a' Ghaidhealtachd

LE IAIN CAIMBEUL NACH MAIREANN, BARD NA LEADAIG.

Message from Principal Sir Donald MacAlister,

Bart.,

K.C.B., M.A., M.D., LL.D., D.C.L., D.Sc, Ph.D., Glasgow University.

I

S toigh leam a' Ghàidhealtachd, is toigh leam gach gleann Gach eas

agus coire an dùthaich nam beann; Is toigh leam na gillean 'nam

fèileadh ghlan ùr, Is boineid Ghlinn-Garaidh mu 'n camagan dlùth.

Is toigh leam 'nan deis' iad o am mullach gu'm bonn, Am breacan, an

t-osan, an sporan's an lann; Is toigh leam iad sgeadaicht' an èideadh an

tìr, Ach 's suarach an deise seach seasmhachd an crìdh'.

Sheas iad an dùthaich 's gach cùis agus càs, Duais-bhrathaidh cha

ghabhadh, ged chuirt' iad gu bàs; 'S ged shàraicht' an spiorad, 's ged leagte

an ceann, Bha 'n cridhe cho daingeann ri carraig nam beann.

Is toigh leam na h-igheanagan, 's b'ainneamh an t-àm Nach bithinn 'nan

cuideachd 'n uair gheibhinn bhi ann; 'S nam faighinn-se tè dhiubh a

dùthaich mo chrìdh', Gun siùbhlainn-se leatha gu iomall gach tìr.

Is toigh leam a' Ghàidhlig, a bàrdachd's a ceòl, Is tric thog i nìos sinn 'n

uair bhiodhmaid fo leòn; 'S i dh' ionnsaich sinn tràth ann an làithean ar

n-òig, 'S nach fàg sinn gu bràth gus an laigh sinn fo 'n fhòid.

Is toigh leam na cleachdaidhean ceanalt5 a bh'ann,

Na biodh iad an dìochuimhn' a nis aig an cloinn,—

An coibhneas, an càirdeas, am bàigh is an t-eud,

Tha cliù dhoibh 's gach dùthaich fo chuairtean nan speur.

Nis tha dùthaich ar gaoil 'dol fo chaoraich's fo fhèidh, 'S sinn 'gar fuadach

thar sàile mar bhàrlach gun fheum; Ach thigeadh an cruaidh-chàs, 's cò

sheasas an stoirm ?— O cò ach na balaich le'm boineidean gorm.

Canar an gaisge's an domhan mun cuairt, Air sgiathaibh nan gaoithean 'ga

sgaoileadh thar chuan, Is fhad 'sa bhios rìoghachd 'na seasamh air fonn,

Bidh cuimhne gu dìlinn air euchdan nan sonn.

As a Trustee of the Fèill Fund, from which An Comunn derives the chief

part of its inadequate income, I am naturally desirous to see its capital

increased. But my special interest in the success of its present effort to this end

is not financial, but educational. An Comunn believes, and I believe, that the

better educated, in the fullest sense of the word, the rising generation of

Highlanders is, the more effective it will be in bringing the Celtic tradition and

the Gaelic genius to bear on the intellectual life of the whole nation. We believe,

nay we know from experience, that a Highland child, who is taught from the

outset bilingually, is more susceptible of higher education in all subjects than a

child, whether in Scotland or in England, whose elementary instruction is given

through English only. We therefore urge that every child, whose home-language

is Gaelic, should be taught in our Highland schools to read and write Gaelic as

he is taught to read and write English. The effect of this training has proved to

be, not only that he gains access to Celtic literature, but that his progress in

English becomes surer and speedier, and his intellectual grasp becomes wider

and stronger. Having already command of two tongues, differing in structure

and idiom, he can make comparisons and observe analogies. He gains in fact

the mental aptitude and versatility that, in the public schools of the south, the

Southron is supposed to gain from his training in Latin or Greek. And he gains

it the more certainly in that his ' second language' is to him a living vernacular,

in which he can constantly exercise himself colloquially, and not a dead

language that he never speaks. Moreover, his Gaelic is a language so rich

phonetically, and so diverse from English in its grammar and phrasing, that he

is thereby prepared, as no Englishman is, for the easy acquisition of other

modern languages. Not only his tongue, but his mind, becomes adaptable, and

he is the better fitted to make headway in foreign lands and new surroundings,

wherever his lot may be cast.

4

MESSAGE FROM SIR DONALD MACALISTER.

I say nothing here, others will say it better elsewhere, of the treasures of

Celtic poetry, art, and music, that are open to an educated Gael, and of the

impoverishment of our civilisation, if these should cease to be cultivated and

transmitted to our successors. My sole point now is that it is worth while to

promote the teaching of Gaelic in Highland schools, because that will make for

the surer success in life of the individual Highlander, and enable him to render

fuller and better service to his nation and to the Empire.

The Feill —Its Purpose.

BY MALCOLM MACLEOD, Ex-President

of An Comunn.

H

IGH hopes are being centred upon the Fèill, and great issues hang upon

its success. Its purposes have been fully set forth in the documents issued

by its promoters, and it is therefore not necessary to do more than merely

refer to them. Indeed, they may all be summed up briefly in the statement that

An Comunn has reached a stage at which it must have more money to carry on

its work. As the Gaelic old-word puts it with rueful humour, "Cha ruig am

beagan fuilt a th'ann air cùl a chinn 's air clàr an aodainn." Its available funds

are inadequate to permit of the work to which it is already committed being

performed efficiently; expansion of that work, for the time being, is absolutely

THE FEILL ---------- ITS PURPOSE.

5

barred. The truth is that curtailment rather than extension is the prospect that

must be contemplated, failing a substantial addition being made to its

resources.

No one who loves the Gaelic language, or who wishes to see it live, can

regard that prospect with any other feeling than dismay. For, after all, An

Comunn is the only corporate body which, organised on a national basis and

operating on a national scale,, has for its main purpose to safeguard and

promote the interests of the Gaelic language. It has endeavoured to carry out its

self-imposed task in many ways, within the limits prescribed by its restricted

resources, and there is a very real sense in which the financial stringency from

which it now suffers may be taken as one of the best evidences of its success. Its

help is being constantly sought, and, while grateful acknowledgment ought to

be made of the vast amount of labour devoted gratuitously and ungrudgingly to

its work, there is much that can be done only by a judicious and generous

monetary expenditure. What is needed now is that it should widen, not narrow

the scope of its operations, that it should lengthen its cords and strengthen its

stakes.

The experience of An Comunn in the course of its work for the Gael, while

it has revealed the existence of a host of men and women who are in full and

eager sympathy with its objects, and willing to devote their time and their

means to the furtherance of these, has also disclosed the less agreeable fact that

in quarters in which a different attitude might quite reasonably be expected,

there is a condition of apathy and of Laodicean lukewarmness which is most

difficult to conquer. What we have to do is to organize and direct the friendly

feeling and the willingness to help, which so widely prevail, and to rouse the

indifferent to a sense of their responsibility. That can be done only by

propaganda work on a much more extensive and systematic plan than has

hitherto been possible. Missionaries must be sent out who will reach the people

directly, who will appeal to their racial self-respect, and who will strive to kindle

in their hearts a glowing pride in their native language, and a resolute

determination to preserve it. A revival of Gaelic in the home, at the domestic

fireside, would be of inestimable value. If it dies in the home, it will not live

anywhere else. Some of us will never cease to be grateful for the fact that we

grew up speaking both languages from our earliest years, and there is no reason

why the children of all Gaelic-speaking parents should not enjoy this boon. That

is one of the things the value of which we must impress strongly on parents

throughout the Highlands.

The Gaelic-speaking area in the Highlands of Scotland is narrowing at a

pace which is very disquieting to all lovers of the language. The figures revealed

by successive Census returns are an imperative call to those who set any store by

the preservation of the national language, to support every legitimate endeavour

put forth for its retention. It is not yet too late to stop the process of decay. We

have the opportunity now of doing something to help the efforts that are being

made towards this end. Let us avail ourselves of it.

Message from The Right

Hon. Lord Alness,

Lord Justice Clerk.

Message from The Right Hon. David Lloyd

George.

25, OLD QUEEN STREET, WESTMINSTER,

LONDON, S.W.I. ph

August) I Q2 6 .

Dear Mr. MacDonald,

I was deeply interested in reading about the proposed Great

Fèill in aid of the Fund of An Comunn Gàidhealach. Its intention is to aid a

noble cause—the perpetuation of the language and customs of a part of the

great race which has inhabited these Islands since the most distant and dim

ages.

Old things have of themselves no right to continued existence if they

become a drag on human progress, and especially so if they can easily be

substituted by others which are more advantageous. No one, however, will

dare contend that Scotland could be occupied by a finer race than the

Gaelic-speaking Celt. If the manly qualities of that race are fostered by a

knowledge of its language, then indeed your Fèill will fulfil a worthy object.

I have no doubt a knowledge of the language and customs of their

ancestors will help each succeeding generation to maintain in their hearts and

minds characteristics which have done so much for Scotland and the Empire.

As a brother Celt, I wish the Fèill unbounded success.

Ever sincerely,

St. Columba's Influence on Scottish History.

BY REV. PROFESSOR MAIN, D.LITT., D.D., Glasgow

Message from The Right Hon. J. Ramsay

Macdonald.

HOUSE OF COMMONS.

I am delighted to hear of" the efforts that are being made to preserve for

Scotland and the world both the tongue and the spirit of the Highlander. Every

man and woman who has any sense of the ultimate blessings of life, will strive,

in these days of vain and impractical materialism, to keep alive those feelings

of reverence for the worthy, and awe for the beautiful and tender, which are an

essential part of the make up of the true Highlander. Worship is the creative

power of the world. Men must either worship God or false gods, and the folk of

the hills and the heather, the mists and the evening twilight, the sheiling, with

the background of moor and the pine trees, have something in their inheritance

which makes it natural for them to worship after the spirit. Our land may have

fallen on evil days, but let us keep the spirit of our people.

T

HE Book of History tells us that in the year 563 St. Columba landed on

the shores of Iona, that he built cells for himself and his twelve devoted

companions, that he founded a little sanctuary for the worship and glory

of God, that he sailed out and in amongst the isles of the Hebrides carrying the

University.

light of the Christian Evangel into dark places, that he crossed to the mainland

and penetrated as far as the palace of Brude, King of the Northern Picts, whom

he converted to the true faith, that he fought a victorious campaign against the

pagan Druids and won a Kingdom for his Christ. But these were far-off days of

legend and romance, and we narrowly scrutinise every legend and every

romance in our era of criticism and sound sense. Learnedly we admit that there

may have been a Columba, Saint of Erin.

The Book of Adamnan tells us a story of a M i l e s C h r i s t i , who won the

hearts of his disciples, and held them for high and noble enterprise. It is a gem

of inspired biography, and it enthrals the reader until he masters the epic of a

brave apostle, who gave his life for Scot and Pict. And when he reaches the end,

and sees Columba, leaning on the breast of the faithful Diormit, give his last

blessing to the stricken monks, then he says with reverent voice—there must

have been a St. Columba.

But the Book of Life tells us most of all. Go to the Sacred Isle, breathe its

air laden with holy tradition, let well-nigh fourteen centuries roll past you as in

a dream, and every doubt will vanish. Begin your pilgrimage at the green sward

of Martyrs' Bay, where lay the bodies of fallen Kings and Chieftains on their

way to burial; then walk past the Nunnery and St. Oran's Chapel, stand near

the Abbey and gaze upon the Pisgah of Iona, then, in leisured mood, traverse

the island till you reach the Bay where Columba landed,—and these ancient

sites will force your verdict —there -was a St. Columba.

Our heroic man was a Monk, a Missionary, and a Statesman. His was a

happy family of " Island-Soldiers." Some of these were alumni, novices of the

faith; some were operarii, workers

IO

ST. COLUMBA'S INFLUENCE ON SCOTTISH HISTORY.

who cared for the wants of the Monastery; and some were senioreSy the

equipped Monastics who performed the daily round of the priestly office. In that

family St. Columba was the Abbot, but he was more than Abbot, he was

undisputed King. There were in him a dignity that impressed all men, and a

geniality that won all men, for never was autocrat and aristocrat more beloved;

he was passionate and masterful, yet he was a saint and a servant; he was an

Evangelist in foreign lands, but no man was greater patriot in love of Erin.

How great was the influence of that man! The history of Scotland began

with him, and in the sixth-century conversion of the Picts the first step in the

consolidation of our country was taken. It was he who restored and

emancipated the Kingdom of the Scots in Dalriada, and, therefore, prepared the

way for a union of Scot and Pict. In very truth, St. Columba was a founder of

Nations.

" Well may the Celtic people remember Columba with grateful devotion—a

devotion that seems folly to those who do not know his history. They are the

better to this hour because he lived." John Campbell Shairp's words are true.

The Gael with his precious heritage of a language brimful of poetry, of a land

majestic in its rugged contours, of a religion reverent and tenacious—the Gael

can never forget Columba. Nor can the Lowlander, for he too has shared many a

blessing that overflowed from the riches of a noble and abiding tradition. So

long as Scotsmen love their country and fear their God, the name of St.

Columba will be remembered and upheld.

ST. COLUMBA'S BENEDICTION TO IRELAND.

Carry with thee, thou noble youth, My

blessing and my benediction, One half upon

Erin, sevenfold, And half on Alba.

Take my blessing with thee to the West; Broken is my heart in my

breast; Should sudden death overtake me It is from my great love

of the Gaedhil; Gaedhil! Gaedhil! beloved name!

Astray in Appin

By NEIL MUNRO, Author of " The Lost Pibroch," " The New Road," etc., etc.

I

HAD been fishing for a week, with moderate success, in Loch Daile Mhic

Chailein, private water which belonged to Fas-nacloich. The weather had been

dry for weeks ; the sun glared hatefully on Appin all the day, and only in the

evenings was the place restored to that condition of romantic mystery, that

agreement with its history, which renders Appin always so peculiarly

fascinating.

Glen Creran—heaven be thanked !—lies out of the way of common traffic,

and the woods of Fasnacloich are even yet as lonely and remote as when the cry

arose round the House of Fear, and the Stewarts trembled guiltily at the news

of the death of Colin Campbell. A new house has been built at Fasnacloich, they

tell me, and Fasnacloich itself has found a new proprietor; but when I was there

a guest of Stewarts, the house was little more than a single cottage with some

iron bungalows in the grounds about it to accommodate the overflow of

shooting and fishing visitors.

They

were—myself

included—the

oddest,

most

incongruous

mixture—soldiers, artists, attaches, lawyers, ladies, and even a lord or two. I

remember one particularly, a Cecil, who looked so like his brother Salisbury,

though in truth a simple, genial English farmer squire, that I never could be at

ease with him. A gay party of good souls, quite ready to swop flies or lies, or gaff

a salmon for you, but someway I was out of it, since the atmosphere was wholly

English, and my quest in Appin was the " genus loci." No matter though a piper

played the rouse each morning, and at dinner made the others doleful by

parading round the table playing pibrochs, I felt this wasn't strictly speaking

Appin.

It could be Appin only when I was alone, when I climbed to Ben Mhir na

Ceisich, or rambled in the woods, walked over the ruins of the sheilings, or by

the otter-haunted river to Loch Creran-head. But even more particularly was it

Appin when the little lake in front of Fasnacloich was like a mirror through

which salmon and sea-trout multitudinously crashed all day, tempting and

taunting the chagrined angler, and I pushed my boat into the embouchure of

the inflowing river, from whose dim, cool, dripping, and mysterious recesses I

could look as from a cave through a vista of dense overhanging trees to an

Appin flooded with light and colour. Round me the fish plowted, and the

water-vole, and in the calmest noon the foliage was full of curious whisperings,

movements, hints of espionage. What a place for love or murder!

But better still, more sane, more spacious, free, and fairy, was the spirit of

the evening hour in Fasnacloich, when the yellow badger's moon hung over the

scented valley, and the woods were sombre dark, and the hills became more

close and lofty, and the little loch had a crossing causewayed with pure gold. In

such an hour the pipes of Cameron, heard upon the shore, expressed most

poignantly the soul and story of the land of Appin.

I tired of the glassy lake, though, indeed, my fishing was a sheer pretence,

and set out one morning, early, on a visit to Dal-ness, a place I had written

about, but at the time had never seen.

Dalness lies over a dozen miles away, in an angle of Glen Etive, across a

trackless country, utterly forsaken, save by bird and deer, and it was necessary

that part of the way at least I should have a guide. I found one wholly to my

mind in the tenant of Glenure.

The house he dwelt in is renowned in Highland history, for it was the home

of the Red Fox—Colin Campbell, and Campbell's blood cries from the floor. It

was from here, as judicial factor, that he squeezed the rents from the reluctant

Stewarts; it was to an upper chamber of it that his corpse was carried after he

had fallen before the bullet of the assassin. The story of "Kidnapped" would

never have been written, if there had not been this little farmhouse under the

sinister shadow of the last of the mighty yew-trees which have given Glenure its

name. A little farmhouse, I have called it, but in truth it had in some respects

the aspect of a keep, with enormous fire recesses, massive walls and shutters,

and an entrance barred by beams of oak that slid into channels in the masonry.

If the house was built for Colin Campbell, it was built for a man who knew he

stood alone, and had to sleep at night among his enemies.

Mackay took me up the glen, which has no road, since it really leads to

nowhere, and his house at the entrance is the only one it holds. We walked high

up on the hill-side on a shepherd's track, as the old Highlanders seem to have

done in nearly all the narrower glens in olden times, before the age of wheels,

doubtless because it was easier walking there than in the troughs created by the

burns, which would be hampered by stones and swamps, and wind-sown

brush-wood. A wild and narrow glen, shut in by hills precipitous, it is only in

jutting roots at intervals that it recalls its worn-out destiny as a place where the

mountain archers one time got their yew.

That old tradition of Glenure, Mackay recalled, and many others of the

district, for though young he had the spirit of the seanachie. Of pipes and pipe

tunes, too, we talked (himself an adept), and Gaelic songs, and midway up the

valley we saw, on the other side, a golden eagle swooping down upon her nest,

at a lower altitude than our own. " And now," said my guide at last " you can

easily find the way; go over the hill till you come to two small lochans, and go

down the glen they are at the head of.'1 He must have said which side I was to

keep the lochans on when I came to them, but he had wakened, by his talk, an

interest in other things than those of the present moment, and I heard in an

abstraction and pursued my way alone in dreams.

The most bewildering glen ! It was a cul-de-sac! I stared, disquieted, at the

barrier which seemed a living avalanche of stones, the " fragments of an earlier

world "; then, knowing I was wrong, but unable to amend my error, I painfully

made my first essay at serious Alpine climbing. How long I took to reach the

summit of the eol (and mostly on hands and knees), over this torrent of

enormous boulders, I do not remember, but when I had reached the top and

looked back in amazement and alarm at the glacis I had scaled, the sun was

high in heaven, and the ardour of a hot day come. Before me lay a choice of

glens and a bewildering array of lofty mountain tops, and I had neither map

nor compass. The little lochs my guide had made so much of were invisible. But

certain now that Dalness was no more than a couple of hours away, I plunged

aqross the moor towards the most spacious and inviting opening between the

hills. The lochans came at last to view; I passed them on the left, and now more

confident that all was well, went gaily over heather and through dried-up hag.

Hours passed.

The way became more difficult, broken by rivulets and bogs, the opening

in the hills I had been making for was now impracticable, and the hill itself

(Ben Trilleachan, as I learned later) was shouldering me for miles on a course

that left the sun far behind me, where I feared it should not be.

At three o'clock in the afternoon I stood on a dreary waste of moor that,

from all appearance, might have never known the foot of man, and realised that

I was lost in Appin. I had been lost in the hills before at night, but in that there

was no ignominy, and at worst it was there a case of waiting till the dawn; here

I was lost in dazzling sunshine through a shameful want of observation, and

every step appeared to make my state more hopeless.

There is, in us, who daily walk on beaten roads and paths well marked, a

singular dependence on the engineer, that utterly destroys a sense most

precious to the traveller in desert places—the instinct for the way, the power to

see in various features of the landscape—run of rivulets, or inclination of the

hills—or in bird flight, or sun or wind, a certain kindly guidance Nature gives to

all who understand her. But take your man of roads and guide-posts, and leave

him to himself in many of the countless moors that lie between the beaten

tracks of the Highlands, and he will learn with fear the limitations of a modern

education.

There is only one way of being lost in such circumstances, and I need not

dwell on the sensation, with its curious mingling of amazement, panic,

self-contempt, recrimination, and hysteric humour. I was lost, and there was,

for the time, an end of it, until at last a fragment of the savage common-sense

came back to me, and I recalled that the water from the tiniest mountain well

can find its way to sea, that rivulets run to burns, and burns to rivers, and that

never a decent river flows in Scotland but has a road beside it.

Late that evening I came plunging down the lower slopes of Trilleachan,

and found myself upon the shores of dark Loch Etive. There was only one house

visible, and a woman working in a field.

" What do you call this place?" I asked, and she regarded me with some

surprise.

" Barrs," she replied.

" How far is it to Dalness?" I asked her then.

She thought a while, and then said, " Twelve or thirteen miles, but there's

no road there from here." " But how do you get out of here when you want?" I

asked, and then she told me nobody ever wanted out of there except sometimes

the shooting tenant, and then he put up a flag and stopped a passing steamer.

There was no steamer till the following day, she added, quite unnecessarily.

I went up to the shooting lodge of Barr, and was met at the door by a man

in evening clothes. " I have walked from Fas-nacloich," I remarked, with

eloquent simplicity, " and I got lost."

" By George, that's fine!" he said, with a kindling eye; "come in and have

some dinner. This is the loveliest day! My regiment's just got the route for

Africa, and I must flag the boat tomorrow." We flagged the boat on the morrow,

and a few months later he was dead on the battlefield.

Tuireadh an t-Saoidh.

LE IAIN MACCORMAIC, F.S.A. (Scot.) Bàrd a' Chomuinn

Ghàidealaich.

S

GRIOB gun d' thug mi do'n doire Far an goireadh na h-eoin, Chunn'cas ann

leam croinn allail A' sealltuinn maiseach fo'n cròic. Cuid diubh sleaghach

àrd dìreach, Toirt deagh ìgh às a' ghrunnd, 'S duilleach bholtrach na cìr-oir

A' moladh mìlseachd an driùchd.

Cuid a' nochdadh an spèireid Le 'bhi èigneach 'nan tighinn,

Oir rinn langaid a' gheamhraidh Am maoth mheanglain a'

mhilleadh. Cuid a sìor dhol an deachamh, 'S air fàs seachte

gun sùgh, :S cluinnear crònan nam beachan A' tòrradh meala

fo 'n rùsg.

Ach an rè bha mi 'siubhal

Feadh fireach nan crann,

Fhuair mi fòghlum thug fios domh

Gnè an lios so a bh' ann.

B'iad croinn-amhuil gach cànain

O linn Adhaimh a nuas.

29

ASTRAY IN APPIN.

ASTRAY IN APPIN.

15

■

TUIREADH AN T-SAOIDH.

Is b'e 'chnead mi a' chraobh Ghàidhlig

A bhi gun àbhachd gun snuadh,

A freumhan sàighte anns an lombar,

Cuid diubh lobhta gun tuar.

I gun ùireadh gun todhar,

Gun aon chobhair o a sluagh,

Gun iad uiread's bhi rùnach

Ri duis ùr-ghlan nam buadh.

Ach iad uile 'g a dìobradh.—

'S mòr mo mhì-ghean 'g a luaidh.

Och! a shìol nan laoch tapaidh A

sgaoileadh bratach ri gaoith, 'S a rùsgadh

gòrm-lannan tana Gach uair a

chasaidteadh ribh—■ Nan do sheas sibh

cho fearail Cùl ealdhain' 'ur saoidh, 'S a

rinn sibh cho eudmhor Cùl beurl' nach

buin duibh, Cha b' ann 'na sìneadh an

euslaint', 'S an lèigh air bheag suim, A

bhiodh cànain nam beur-bheann 'Tha cho

geur-bhriathar grinn.

Ach a dh' aindeoin a' mhìobhaidh, A thug

dì-mheas d' a cloinn, A chuir a thaobh i

mar chrìonaich, 'S a leig air dìochuimhn'

a loinn, Tha de neart-ghloir 'na fìon-fhuil

Na chum ìoc-shlàint' r'a com, 'S chithear

fhathast a geugan Làn èifeachd 's a' choill.

Wi' mom'e a Vow and locked embrace Our

parting was ja tender;

And, pledging ajt to meet again, We tore oursels

asunder."

BY I'IT'1 ENDRIOH MACGILL[VRAY, SC.

Dealachadh nan Rathad

L E D OMHNALL M AC N A C EARDAC H , (E ILEAN B HAR RAIDH ), U G HDAI R AN

D EALBH - CHLUICHE , " C ROIS - TA RA ," etc.

Saoibhir sìth nan sian an nochd air Tìr an Aigh, Is ciùine ciùil nan

Dul ag clùmhadh Innse Gràidh, Is èasgaidh gach sgiath air fianlach

dian an Dàin Is slighe nan seann seun a' siaradh siar gun tàmh.

--

A

GUS thall—fada thall, a Ghaoil, fhreagair Mac Talla,—" a> siaradh siar gu

bràth." Sheas mi, a Ghaoil, fo iongnadh, oir bha rud-eigin anns a' ghuth

agus ann an aigne a' chiùil a chuir gaoir air mo shiubhal, agus seun air nV

aigne fèin. Bha rudeigin ann a bha mo spiorad fèin ag aithneachadh agus a'

co-fhreag-airt. B' fheàrr leam na rud air an t-saoghal, a Ghaoil, gum b' urrainn

mi an t-aigne ud ainmeachadh dhuit,—aigne a dh' agallas ri spiorad mac a'

Ghàidheil mu àilleachd na Fìrinn, a tha os cionn eòlais; aigne a chruinnicheas

fa chomhair oidheam dìomhair gach teud a bhuineas do chruit mion-oilean nan

cinneach Ceilteach,— seadh, a Ghaoil, Cruit Chiùil na Dìleann !

Ach cò a bh' ann ? Cha robh neach, a Ghaoil, 'nam shealladh. Bha grian

deireadh foghair ag èaladh le leathad nan speur, agus thall ri bunnacha-bac bha

Innse-Sgeoil agus Tìr-an-Aigh, laiste le lasair solus nan seann sòlas. Sìos

troimh Ghleann Sianta, bha rathad soilleir an triall a' siùdan mu bhonn nan

cnocan, gus an robh e a' dol às orm 'na stiallan caola aig iochdar Cadha na

h-Imriche. Leum clacharan, a Ghaoil, a mach às an toll; às an bhothan bheag

anns an do thog e a theaghlach, agus gun ghuth idir a thighinn às a cheann, a

Ghaoil, ghabh e le aon si fheadh sìth tarsuinn a' ghlinne, is aghaidh do'n deas.

Chuir mo smaoin trioblaid orm, a Ghaoil. Gu dè a thàinig air an t-saoghal

? Carson nach d' thubhairt an clacharan ud, " Seach !—Seach !—Seachainn !"

mar a b' àbhaist dha? Gu dè a chuir cho balbh e an diugh, agus a dh' fhàg cho

geal leathann an sgrìob air an robh mi cho eòlach na earball, is e a' taisdeal às?

Ach

i8

DEALACHADH NAN RA THA D .

d rithisd dh' èirich deò a' chiùil, a Ghaoil, agus dh' fhairich mi an aon seun a'

tighinn orm o Innis na Fìrinn—

Sona com nan cruach le cuimhne làithean aosd' Sona gnùis nan cuan am

bruadar uair a dh'aom, Aoibhinn an duan air meamhaìr bhuain nan gaoth O,

làithean nam buadh ! 'ur n-uaill, 'ur n-uails', 'ur saors'! Agus a rithisd eile, a

Ghaoil, fhreagair guth seachranach Mhic Talla,—« 'Ur luaths, 'ur luaidh, 'ur

gaol!"

Thug mi a chreidsinn orm fèin gun robh aobhar a' chiùil na b' fhaisge dhomh

an turus so, a Ghaoil, agus sùil gun tug mi air mo chùlaibh chunnacas ùghdair mo

shonais agus m'iongnaidh leth-• fhalaichte fo sgeothall creige ri taobh an rathaid. "

Mo bheannachd air t' anam, 'aois-cheoil nam buadh!" B' ann rium fèin a thug mi

briathar mo bheannachaidh, a Ghaoil, oir bha mo chridhe làn, ionnas gun tugadh

mo bhilean breith-buidheachais gun fheith-eamh idir ri rian mo thoile.

A dh' aindeoin gach fìamha, faiteachais, agus taom eile a thàinig a steach

orm, ghabh mi a null 'ga ionnsuidh, a Ghaoil. Saoil an robh mi a dèanamh na

còrach ?

A' leigeil às na cruite às an tug e an ceòl, dh' èirich an seann-duine 'na

sheasamh, a Ghaoil, 'gam bheannachadh, agus, an càinnt uasal oileanta nan

daoine, dh' fhàiltich e mi fèin agus mo thurus mar bu mhodh agus deas-ghnàth

riamh do chlann a' Ghàidheil a chur roimh choigreach. 'Na ghnùis dh' aithnich

mi, a Ghaoil, oighreachd òirdhearc mo chinnich; flathalachd, fiù agus

feardhachd nam fear fìrinneach, agus 'na cheann an dà shùil a bu shoilleire, ach

eadhon fòs a bu duatharaiche a chunnacas riamh an cruthachd bàird. Am

fianuis urra cho ainneamh, a Ghaoil, 'sann a dh' fhàs mi diùid, nàrach, oir

chomh-luath agus a theann mi ri a fhreagairt dh' fhairich mi blas mo

theangaidh 'gam bhrath agus 'gam dhìteadh. Ach naisg mi mo chomain, a

DEALACHADH NAN RA THA D .

'9

Ghaoil, anns na briathran a bu deise a dh' èireadh leam, ged is iomadh là o

'n uair sin fèin a chuir cuimhne a shùla-san biorgadh troimh m' aigne.

" Is dòcha leam gur coigreach sibhse air na rathaidean so," ars' esan, is

e ag cromadh a thogail na cruite agus 'ga cur fo a achlais, "ach tha mi an

dòchas nach dìomoì sibh dhomh-sa a bhi ag iarraidh fàth air fois an

fheasgair, a dhèanamh mo thiomnaidh 'san ionad àraid so." Cha ruig mi a

leas innseadh dhuit, a Ghaoil, gun do chuir na briathran neònachas orm.

Carson a leigeadh urra air an t-saoghal rium-sa gnothach cho dìomhair?

Tiomnadh 'san ionad àraid so!

B' fheudar nach robh mi 'ga thuigsinn, a Ghaoil, agus bu chinntiche

dhomh mo fhreagairt a chur an càinnt a cheileadh an teagamh agus an

neònachas a bha ag cur air m' inntinn.. " I s coigreach mi an taobh so gun

teagamh," arsa mise, "agus tha mi ag iarraidh 'ur mathanais air son call 'ur ciùil

a chur oirbh." Sheall e orm, a Ghaoil, mar gum biodh truas aige dhìom, oir bha

cianalas mòr 'na shùilean agus 'na ghuth. " Call mo chiùil orm-sa, a ghràidh?"

ars' esan. " 'Sann air chall a bha an ceòl ud o chionn fhada an t-saoghail, ach is

dòcha gur ann mar sin is mìlse e. Gabh mo leisgeul, a mhic," ars' esan, " air son

a bhi a' dol cho dàna air 'ur n-eòlas, ach an ceòl ud a chuala sibh cha teid a

chrìochnachadh gu bràth." Mar dhealan athair, bhuail rud-eigin de'n eòlas

'nam inntinn, a Ghaoil. Lean an seann-duine air. " Sud an dàn mu dheireadh, a

ghràidh,—an dàn a bhios gu sìorruidh gun cheann gun cheangal; an tiomnadh

air nach ruig dìleabach."

Ghluais an seann-duine gu ceum an rathaid. Thuig mi, a Ghaoil, gun do

rinn mi call nach ìeasaicheadh iùnntas an t-saoghail, agus thòisich dorran dubh

air itheadh mo chridhe, oir mhothaich mi eadar mi is an leus gun robh aon de

theudan na cruite briste air a ghàirdean. An dàn gun chrìochnachadh! Agus

ùghdair an dàin ud nach do rugadh a' falbh ! An robh mi a' dol 'ga leigeil às m'

fhianuis mar sud? Saoil an gabhadh e dhomh an còrr de'n dàn air chor is gun

cuirinn sgrìobhadh air? Saoil an innseadh e dhomh eadhon susbaint nan

smaointean a dhùisg an ceòl ud a thug às mo thoinneamh mì?

Cha ruig mi a leas, a Ghaoil, mo dhearbh-bhriathran fèin aithris dhuit an so;

ach cearbach, lom is gun robh iad, dh' fheuch mi ri mo chridhe a rùsgadh dha. Dh'

fheuch mi, a Ghaoil, an dorus a anma an iuchair ud a thug thu fèin dhomh o

chionn fhada —an iuchair a dh' fhosgail dhomh iomadh glas; a fhuair dhomh

iomadh rèidh-fhuasgladh o'n latha sin. Sheall esan orm, is a shùilean a' dèanamh

tobar-sìolain an clàr m' aodainn, a Ghaoil, agus a' breith air dhà làimh orm

thubhairt e an leth-chagar, " An teid sibh leam ceum de'n rathad?" Sud fèin na

thubhairt e, a Ghaoil, ach shaoil mise gun do leugh mi barrachd is a chuala mi.

Bha a' ghrian air a sgiath a bhogadh an druim an t-saoghail, agus sinn a'

fiaradh an rathaid sìos gu Cadha na h-Imriche. Bha sìth nan seachd seun air a

ghleann. Bha sìth agus seuntachd air gach beò, a Ghaoil, eadhon air an tè òig ud a

bha a' bleoghann na bà air taobh an rathaid. " Gum beannaicheadh Dia sibh," arsa

mo chaomh chompanach, is sinn a' dol seachad oirre, ach freagairt,

20

DEALACHADH NAN RATHAD.

seadh an aon fhreagairt fhial ris an robh dùil agam fèin maraon, cha d' fhuaras,

ged a shaoil mi, a Ghaoil, gun cuala mi srùthlag bheag chaol an t-sruthain a bha

an taobh thall dhìom ag ràdh, " Dia dhuibh fèin."

Air taobh eile an rathaid mhothaich mi clàr sanais, a Ghaoil, a bha a'

maoidheadh greim an lagha air neach 'sam bith a dhèanadh ùtraideachd. "An

leugh sibh-se ana-cainnt na coigridh?" ars' an seann-duine, is esan e fèin a'

toirt sùla air a' chlàr shanais. Bha rud-eigin 'na ghuth a bha coltach ri

cothlamadh faiteachais agus gràine, a Ghaoil; ach a thaobh is nach cuala mi

riamh roimhe am facal ud, seadh, ' na coigridh,' feumaidh mi aideachadh dhuit,

air tàilleabh na thog am facal ud am inntinn, agus na thàinig a steach orm ri a

linn, gun do dhìochuimhnich mi car tiotain gun deachaidh ceist neònach a chur

orm. " Leughaidh mi beagan,—air èiginn," arsa mise, agus mi a' leigeil mo

chudtruim, a Ghaoil, air an ' èiginn '; ach cha d' thàinig de fhreagairt eile às a

cheann, a Ghaoil, ach, " Seadh, a ghràidh, seadh dìreach,—air èiginn."

Bha e 'nam bheachd 'ana-cainnt na coigridh' eadar-theangach-adh, a

Ghaoil, air chor is gun tuigeadh esan aobhar a' chlàir ud, ach mu'n gann a

chruinnich mi mo bhriathran air an ceart-dhlogh-adh, 'sann a chaidh dithis

òganach seachad oirnn, is iad ag comh-luadar cho àrd agus cho gob-chluasach

is ged a bhiodh iad le chèile bodhar. " A n cuala sibh sud?" arsa an t-aosdàna,

is crithinnich 'na cheann, agus a shùilean a' lasadh, a Ghaoil, mar a lasas teine

smàilte. " Nach ann air mo chànain fèin-sa a thàinig an latha? Seadh, " dannsa

ag gabhail àite"! O, a thàsga nam bàrd nach beò ! an èisdeadh sibh ri iasad facail

cho claon agus ceacharra? O, an t-aineolas so thar gach aineolais!—O, an

t-eòlas so as doille na'n t-aineolas!" Bha mi air mo nàrachadh, a Ghaoil. B'

fheàrr leam 'san àm gun robh mo cheum air rathad eile, agus mi 'nam aonar,

air chor is gum falaichmn an trioblaid a bha air m'aigne. Nach iomadh uair a

20

DEALACHADH NAN RATHAD.

chuala is a chunnaic mi fèin "an t-eòlas ud is doille nan t-aineolas?" Nach

iomadh uair a rachainn fèin tuathal mar biodh gum bi do bheul caomh,

carthannach-sa fòs 'gam stiùireadh, —'gam sheòladh air ceumaibh an t-seann

rathaid eòlaich, anns am faic mi na leacan air am bleith is air an cnàmh lom

agus laganach le triall agus tosgaireachd mo dhaoine.

" Ach saoilibh," arsa mise, " a bheil atharrach aca air? Saoil-ibh an ann

de'n deoin fèin a tha iad sud aineolach air teangaidh, air tighinn, agus air

mion-oilean an sinnsir—?" " Seadh," ars' esan, is e ag gabhail a leisgeil a chur

casg air mo chainnt, " saoileam

DEALACHADH NAN RATHAD.

an ann gu dearbh ! Saoileam, a mhic, carson a tha athaill a chràidh fhathast an

21

uchd Goirtean a' Bhliochd? Ach is mithich dhomh-sa, ■ a ghràidh, a bhi ag

greasad orm, oir tha mi cheana anmoch, is falamhachd an latha agus fuachd na

h-oidhche a' fuadach mo dheòine bhàrr àrainn nan tràth caochlaideach so."

Thog mi mo shùil a null ri Goirtean a' Bhliochd, a Ghaoil, feuch am

faighinn oidheam nam briathran. Thall ri bonn a' chnuic chunnaic mi leoba de

ghlasrach ag imlich a steach do gharbh-fhraoch na mòintich, agus thug mi an

aire gun robh an sud is an so beathach ag ionaltradh air a' mhìn-fheur. Ach

mhothaich mi cuideachd, a Ghaoil, gun robh sean athailtean nan àiteach

fhathast ri am faicinn 'na uchd; seadh, ' athailt a' chràidh.' Dh' fhuasgail an

snaim dhomh! Seadh; gun chràdh cha tig is cha choisnear duais no toradh, a

Ghaoil; eadhon mar sin a dh5 fhulaing Goirtean a' Bhliochd a chliabh a bhi air a

reubadh agus air a fhosgladh a dhèanamh cobhair am beoil do na h-àil,—agus

eadhon fòs mar sin a chaidh goirtean ar càllachaidh agus ar mion-oilein-ne

àiteachadh, a dhèanamh cobhair ar càile spioradail agus chinneadail dhuinne.

Agus mar sin uidh air n-uidh, a Ghaoil, lorg mi slighe nan smaointean a

chaidh troimh aigne a' bhàird; ' s e a tha mi ag ciallachadh gun do lorg mi

dhomh fèin aon oidheam phurpail, an comh-shìneadh ri mo chomas agus m'

eòlas air aignidhean duatharach a rannsachadh.

B' ann aig Cadha na h-Imriche, aig dealachadh nan rathad, a thàinig mi gu

mo shuim às na beachd-smaointean ud, a Ghaoil, agus cha b' ann gun arraban

agus mulad a thuig mi gun robh esan air an do ghabh mi a leithid de ghràdh air

thuar m' fhàgail. "Tha sinn a nis aig dealachadh nan rathad, matà, a ghràidh,"

ars' esan, is e ag cur tosd air a cheum, " agus o'n a tha impidh is crannchur an

dàin 'gar tabhairt-sa taobh eile, is èiginn dhomh an rathad gu Port na

h-Iubhraich a dhèanamh air luirg na lacha.J' Chaidh sgaoth eun seachad os ar

cionn, a Ghaoil. Lean a shùil an triall gus an deachaidh am fear mu dheireadh i

sealladh thar ghuala na h-Airde. Chuir e dheth a cheann-aodach, a Ghaoil, agus

le blas nach buineadh do'n t-saoghal 'na ghuth, thuirt e na briathran nach

dìochuimhnich mise gu bràth; " Beannachd leibh a chlann an

t-samhraidh,—sonas leibh 'nar siubhal sìth. Tillidh sibh-se fòs gu 'r

n-annsa,—gu mo chall-sa, gleann mo chridh'."

Bha a mheuran ag cniadachadh teudan na cruite 'na achlais mar gum

biodh e ag iarraidh puing nach robh e ag amas. Chuir mise

22

DEALACHADH NAN RA THA D .

cuideachd dhìom mo cheann-aodach fèin, a Ghaoil, oir bha annlainn mhòr 'gam

ghluasad.

Theann e 'gam ìonnsuidh gus an do leag e a làmh air mo ghualainn. " A

mhic," ars5 esan, " is mise am fear mu dheireadh, —an t-eun mu dheireadh de

5n àl. Is mise am fear mu dheireadh de'n dream ud nach deachaidh an call an

ribe na coigridh; an dìleabach aig an do sguir an dìleab. Dearbh-oighre chan 'eil

ann. Is ro-fhada a tha mi às dèidh chàich."

Bha mi air mo lìonadh le uamhas, a Ghaoil. Sann a bha cianalas neònach a'

teannadh ri criomadh mo chridhe. Ciod è an dìleab? Ciod è a bha air chùl nam

briathran iongantach so? Aig sean bhreac nan sruth a bha dà thrian de'n eòlas,

agus an treasa trian aig an tè nach innseadh do na faoileagan e; aig a' chorra.

" Ach fòs," ars' an seann duine, is e a' dèanamh nàduir de ghreim air mo

ghàirdean, " bidh àil eile am dhèidh, agus eadhon air glùin fhuair na banaltruim

gun dàimh their leanabh a' Ghàidheil, ' dath ! dath!' mar a rinn mise an uchd

blàth mo mhàthar fèin. Agus fòs thig diolacha-dèirce le cridheachan acrach

agus crogan sanntach a dhùsgadh m' uaghach-sa, a dh' iarraidh nan ulaidhean a

thug mi leam 'nam bhroilleach."

" Fòs tuigidh an saoghal dàn duatharach mo chinnich am beul an là agus

air bhilean na h-oidhche, agus thar sheachd buidhrichean ciana an domhain

thig iad a shireadh lorg mo cheum,—a chomharrachadh taibhsealan mo

ghabhalach, eadhon am fliche nan tonn, eadhon fòs gu ceann na slighe a theid

siar gu Tìr nan Og."

Ach mar gun tigeadh rud-eigin de allaghrabadh air ruith a sheanchais, a

Ghaoil, chaochail e gnùis a bhriathran, agus ag càradh na cruite a bha e ag

caidreamh 'na achlais fèin ann am achlais-sa, thuirt e rium car mar so—" Ach

so, sud dhùibh-se mo dhìleab-sa; mo dhìleab-sa o chraoibh nan cliar, le m'

dheoin, le m' bhriathar's le beannachd Dhia,—le beannachd Dhia." Agus cha b'

DEALACHADH NAN RA THA D .

23

e so uile na chuir neònachas orm, a Ghaoil, oir an sin thug e a mach às a

bhroilleach rola meambrana air an robh làmh-sgrìobhadh de an do sfhabh mi

annas ro-mhòr.

~Cha mhath a thog mi, a Ghaoil, na briathran a thuit uaidh an àm dha an

rola so a chur 'nam làimh, ach ar leam gun d' ainmich e I agus rolan de

mheambrana a chaidh air chall.

Ach is iomadh rud a chuala mi, a Ghaoil, aig dealachadh nan rathad air

nach cubhaidh dhomh luaidh a dhèanamh aig an àm, agus, a chumail ri mo

ghealltanas, cha mhotha a bheir mi guth riut air dealachadh nam beò, no

seòladh air triall an fhir a bheannaich mi aig Cadha na h-Imriche. Ach so

faodaidh mi innseadh dhuit, a Ghaoil, oir tha fhios agam gum bi thu ri

feòraich. 'S e " Dàn nan Dul " is ainm do'n dàn ud air nach deachaidh crìoch,