Causes, History, and Violence of the Crusades

advertisement

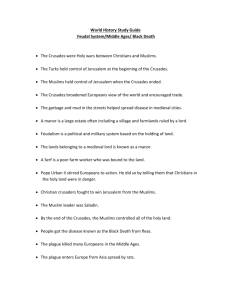

Causes, History, and Violence of the Crusades Why were the Crusades launched? Were the Crusades primarily religious, political, economic, or a combination? There is a wide variety of opinion on this matter. Some argue that they were a necessary response by Christendom to the oppression of pilgrims in Muslim-controlled Jerusalem. Others claim that it was political imperialism masked by religious piety. Still others argue that it was a social release for a society that was becoming overburdened by landless nobles. Christians commonly try to defend the Crusades as political or at least as politics being masked by religion, but in reality sincere religious devotion — both Muslim and Christian — played a primary role on both sides. It's little wonder that the Crusades are so often cited as a reason to regard religion as a cause for violence in human history. The most immediate cause for the Crusades is also the most obvious: Muslim incursions into previously Christian lands. On multiple fronts, Muslims were invading Christian lands to convert the inhabitants and assume control in the name of Islam. A "Crusade" had been underway on the Iberian Peninsula (Spain) since 711 when Muslim invaders conquered most of the region. Better known as the Reconquista, it lasted until the tiny kingdom of Grenada was reconquered in 1492. In the East, Muslim attacks on land controlled by the Byzantine Empire had been going on for a long time. After the battle of Manzikert in 1071, much of Asia Minor (modern Turkey) fell to the Seljuk Turks, and it was unlikely that this last outpost of the Eastern Roman Empire would be able to survive further concentrated assaults. It wasn't long before the Byzantine Christians asked for help from Christians in Europe, and it's no surprise that their plea was answered. A military expedition against the Turks held out a lot of promise, not least of which was the possible reunification of the Eastern and Western churches, should the West prove capable of defeating the Muslim menace which had for so long plagued the East. Thus the Christian interest in the Crusades was not only to end the Muslim threat, but also to end the Christian schism. Aside from that, however, was the fact that if Constantinople fell then all of Europe would be open to invasion, a prospect that weighed heavily on the minds of European Christians. Another cause for the Crusades was the increase in problems experienced by Christian pilgrims in the region. Pilgrimages were very important to European Christians for religious, social, and political reasons. Anyone who successfully made the long and arduous journey to Jerusalem not only demonstrated their religious devotion, but also became beneficiaries of significant religious benefits. A pilgrimage wiped clean one's plate of sins (sometimes it was a requirement, the sins were so egregious) and in some cases served to minimize future sins as well. Without these religious pilgrimages, Christians would have had a harder time justifying claims to ownership and authority over the region. The religious enthusiasm of the people who went off on the Crusades can't be ignored. Although there were a number of distinct campaigns launched, a general "crusading spirit" swept across much of Europe for a long time. Some Crusaders claimed to experience visions of God ordering them to the Holy Land. These usually ended in failure because the visionary was typically a person without any political or military experience. Joining a Crusade was not simply a matter of participating in military conquest: it was a form of religious devotion, particularly among those seeking forgiveness for their sins. Humble pilgrimages had been replaced by armed pilgrimages as church authorities used the Crusades as part of the penance people had to do to repay sins. Not all of the causes were quite so religious, though. We know that the Italian merchant states, already powerful and influential, wished to expand their trade in the Mediterranean. This was being blocked by Muslim control of many strategic seaports, so if Muslim domination of the eastern Mediterranean could be ended or at least significantly weakened, then cities like Venice, Genoa, and Pisa had a chance to enrich themselves further. Of course, richer Italian states also meant a richer Vatican. In the end, the violence, death, destruction, and continuing bad blood that last through to the present day would not have occurred without religion. It doesn't matter so much who "started it," Christians or Muslims. What matters is that Christians and Muslims eagerly participated in mass murder and destruction, mostly for the sake of religious beliefs, religious conquest, and religious supremacism. The Crusades exemplify the way in which religious devotion can become a violent act in a grand, cosmic drama of good vs. evil — an attitude which persists through today in the form of religious extremists and terrorists. Causes, History, and Violence of the Crusades Violence in the Crusades The Crusades were an incredibly violent undertaking, even by medieval standards. The Crusades have often been remembered in a romantic fashion, but perhaps nothing has deserved it less. Hardly a noble quest in foreign lands, the Crusades represented the worst in religion generally and in Christianity specifically. Two systems which emerged in the church deserve special mention as having contributed greatly: penance and indulgences. Penance was a type of worldly forgiveness, and a common form was a pilgrimage to the Holy Lands. Pilgrims resented the fact that sites holy to Christianity were not controlled by Christians, and they were easily whipped into a state of agitation and hatred towards Muslims. Later on, crusading itself was regarded as a holy pilgrimage — thus, people paid penance for their sins by going off and slaughtering adherents of another religion. Indulgences, or waivers of temporal punishment, were granted by the church to anyone who contributed monetarily to the bloody campaigns. Early on, crusades were more likely to be unorganized mass movements of "the people" than organized movements of traditional armies. More than that, the leaders seemed be chosen based on just how incredible their claims were. Tens of thousands of peasants followed Peter the Hermit who displayed a letter he claimed was written by God and delivered to him personally by Jesus. This letter was supposed to be his credentials as a Christian leader, and perhaps he was indeed qualified — in more ways than one. Not to be outdone, throngs of crusaders in the Rhine valley followed a goose believed to be enchanted by God to be their guide. I'm not sure that they got very far, although they did manage to join other armies following Emich of Leisingen who asserted that a cross miraculously appeared on his chest, certifying him for leadership. Showing a level of rationality consistent with their choice of leaders, Emich's followers decided that before they traveled across Europe to kill God's enemies, it would be a good idea to eliminate the infidels in their midst. Thus suitably motivated, they proceeded to massacre the Jews in German cities like Mainz and Worms. Thousands of defenseless men, women and children were chopped, burned or otherwise slaughtered. This sort of action was not an isolated event — indeed; it was repeated throughout Europe by all sorts of crusading hordes. Lucky Jews were given a last-minute chance to convert to Christianity. Even other Christians were not safe from the Christian crusaders. As they roamed the countryside, they spared no effort in pillaging towns and farms for food. When Peter the Hermit's army entered Yugoslavia, 4,000 Christian residents of the city of Zemun were massacred before they moved on to burn Belgrade. Eventually the mass killings by amateur crusaders were taken over by professional soldiers — not so that fewer innocents would be killed, but so that they would be killed in a more orderly fashion. This time, ordained bishops followed along to bless the atrocities and make sure that they had official church approval. Leaders like Peter the Hermit and the Rhine Goose were rejected by the church not for their actions, but for their reluctance to follow church procedures. Taking the heads of slain enemies and impaling them upon pikes appears to have been a favorite pastime among crusaders. Chronicles record a story of a crusader-bishop who referred to the impaled heads of slain Muslims as a joyful spectacle for the people of God. When Muslim cities were captured by Christian crusaders, it was standard operating procedure for all inhabitants, no matter what their age, to be killed. It is not an exaggeration to say that the streets ran red with blood as Christians reveled in church-sanctioned horrors. Jews who took refuge in their synagogues would be burned alive, not unlike the treatment they received in Europe. In his reports about the conquest of Jerusalem, Chronicler Raymond of Aguilers wrote that "It was a just and marvelous judgment of God, that this place [the temple of Solomon] should be filled with the blood of the unbelievers." St. Bernard announced before the Second Crusade that "The Christian glories in the death of a pagan, because thereby Christ himself is glorified." Sometimes, atrocities were excused as actually being merciful. When a crusader army broke out of Antioch and sent the besieging army into flight, the Christians found that the abandoned Muslim camp was filled with the wives of the enemy soldiers. Chronicler Fulcher of Chartres happily recorded for posterity that "...the Franks did nothing evil to them [the women] except pierce their bellies with their lances." Ten vocab words – do before you read the article – 30 points One sentence per paragraph – 18 sentences – 36 points