BAA Anton du Toit 2008 - American Accounting Association

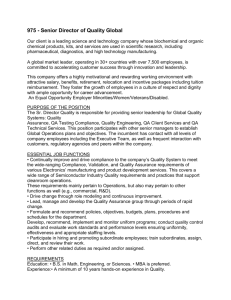

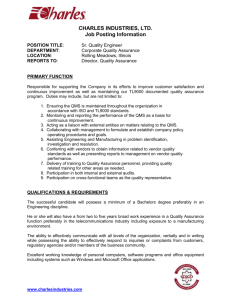

advertisement