Competencies TACT 2008

advertisement

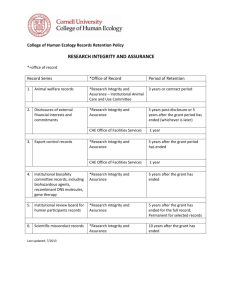

Competencies and thinking skills required in modern auditing for dealing with sustainability assurance TACT Public Sector Auditing Symposium 2008, Midrand, 30 January 2008 Anton Du Toit Academic Director: Accounting Monash South Africa Telephone: 083 252 0910 E-mail: Anton.Dutoit@buseco.monash.edu Abstract Best practice in corporate governance (including sustainability reporting) has prompted the accountant and auditor to start considering non-financial information. The competencies and thinking skills of sustainability assurance providers (particularly auditing firms) are insufficiently listed or described in existing literature and in assurance reports. This paper explores which competencies and thinking skills auditing firms should possess in this regard. It was found that there is an urgent need for research to be done in this area. It is recommended that international guidelines and literature should include the relevant competencies and thinking skills. Key words assurance provider/auditor audit of non-financial information auditing firm competencies competencies of assurance provider corporate governance standards on assurance sustainability assurance sustainability reporting © Anton Du Toit, 2008 1 1. Introduction For many years during the previous century, large companies and corporations produced and published only one kind of stakeholder report – the annual report. The annual report includes the annual financial statements, audited by an external and independent auditor, usually belonging to and accredited by a professional body which is a member of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs) is used as a benchmark for financial reporting and disclosure (UNCTAD 2006). In recent years the annual report has become supplemented by a non-financial section on sustainability (a corporate sustainability report, called a “sustainability report” in this paper), either included in the annual report or published separately (ACCA 2004, Du Toit 2007). The sustainability section or report is often audited to some extent, resulting in an assurance report. This field is called “sustainability assurance”, which is often provided by auditing firms. (The terms “auditing firm” and “auditor” are used throughout this paper. However, “accounting firm” and “accountant” are sometimes used in the literature in the same sense.) The auditor and the auditing firm involved in sustainability assurance should possess certain competencies and skills that are referred to in documents on professional standards and in other literature. These competencies required are, however, very seldom listed or properly described in literature and in research reports and papers. Furthermore, these competencies are almost never mentioned or described in the report of the assurance provider. As there is insufficient research on and information about the competencies of the assurance provider, this paper explores which competencies and thinking skills an auditing firm should possess as an assurance provider. The research approach on which this paper is based is interdisciplinary (covering, amongst other, accounting, auditing, business management, social and health sciences, language sciences), which means that the traditional model of hypothesis and empirical research applies to some extent only (Wilson 2003). The scope of this paper is the competencies and thinking skills of the assurance providers (literature survey in paragraph 3). There are two types of assurance providers, broadly speaking. They are the major auditing firms and “other” assurance providers, such as certification bodies. Literature from both these sources were included in the literature survey. The most comprehensive description of competencies was found in the publications of the “other” assurance providers. The most important source in this regard was from the International Register of Certificated Auditors (IRCA 2007) . In this publication, only the competencies of the “Lead Sustainability Assurance Practitioner” were reviewed, as this qualification level bears the closest relationship to an auditing firm. The discussion in this paper excludes any reasons for having sustainability reports and even for having assurance on these reports. A brief introduction to corporate governance is set out in paragraph 2, to provide a framework for further discussion. The paper provides, in a literature review, a background to the field of sustainability reports and sustainability assurance. It continues to review literature on the competencies and thinking skills required of assurance providers. These are all done in paragraph 3. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 2 2. Corporate Governance introduction A proper definition of corporate governance is provided by Payne (2002): Corporate governance can be defined as the manner in which an organisation is directed and controlled with a view to ensuring the achievement of its objectives in a sustainable manner within an environment of accountability to its stakeholders. It is about leadership with integrity. The King III report of the King Committee on Corporate Governance is on its way (IoD Bulletin 2007). It will take into account the changes in the Companies Act (amendments of 14 December 2007, as well as the Companies Bill that will replace the old Companies Act in its entirety), the Auditing Profession Act, and the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act (Act 12 of 2004). Over and above these, the public sector auditors have to take into account the PFMA (Public Finance Management Act, Act 1 of 1999, as amended by Act 29 of 1999), the MFMA (Municipal Finance Management Act, Act 56 of 2003), the Public Audit Act (Act 25 of 2004) and other requirements such as the Protocol on Corporate Governance in the Public Sector (Department of Public Enterprises 2002). All these documents contain reference, to a smaller or larger extent, to quite a number of corporate governance best practices, such as having proper audit committees (each contains at least a section on this requirement). It simply means that public sector auditors have to broaden their scope beyond the auditing of financial data only. It is, however, noteworthy that not one of the documents listed here, contains any reference to the word or concept “sustainability” or “corporate governance”. The PFMA and the MFMA do refer to “financial governance” and “corporate plan” and the MFMA requires the audit committee to ensure “effective governance”. The Code in King II (IoD 2002) is applicable (amongst others) to Public sector enterprises and agencies that fall under the PFMA and the Local Government: MFMA including any department of State or administration in the national, provincial or local sphere of government or any other functionary or institution, exercising a power or performing a function in terms of the Constitution or a provincial constitution; or exercising a public power or performing a public function in terms of any legislation, but not including a Court or a judicial officer, unless otherwise prescribed by legislation. To put corporate governance and the current King II (IoD 2002) in proper business perspective, one must go back to the basics of ethics and business ethics. Corporate governance is a new term used in formalising old principles laid down over many decades and centuries in the field of business ethics. Corporate governance is a part of business ethics. Business ethics, again, is part of ethics, which is even wider (Du Toit 2007) The relationship between ethics, business ethics and corporate governance can be graphically depicted as in Figure 1. King II (2002) states the following: By its very nature, corporate governance has an ethical dimension that can be viewed as the moral obligation for directors to take care of the interests of investors and other stakeholders. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 3 Ethics Business ethics Corporate Governance Figure 1. The relationship between ethics, business ethics and corporate governance (Du Toit 2002 as quoted by Du Toit 2007) The following descriptions are based on research performed by Du Toit (2007): Ethics (morality) is the study of what is good and right amongst people. If one acts in such a way that one does what is best for the people around one and for oneself, one acts ethically or morally. Ethics, therefore, involves the choices people make in dealing with other people. The “Golden Rule” remains: Do unto others, as you would like them to do unto you. Business ethics deals with ethics in business. It therefore deals with ethics in the business world. People in business should make the correct decisions, and they should also act morally or ethically. Business ethics is the ethics applied in business when making decisions, so that the decisions are good and right for the business and/or also for other people (persons, communities or structures) influenced by those decisions. The decisions of a business are made by the directors and, to a lesser extent, by the management. In making decisions, they have to consider the effect of each decision on all people and structures involved. If a business takes other people's/parties' interest into consideration, what does it actually mean? It means that the following ethical principles should be involved: Honesty Integrity Keeping promises Loyalty to the business enterprise, to the government, the business world, society, customers, owners, management and employees. Fairness Caring for others Respect for others Responsible citizenship Pursuit of excellence 4 © Anton Du Toit, 2008 Accountability If a business should abide by these principles, everyone will be loyal to the business and will respect it. Society, government, other businesses, clients and employees will also respect it. The business will thrive and grow. Taking all of the above into account, one should identify all the relevant stakeholders of a business in order to determine the responsibilities between the various stakeholders, and all that remains then, is to act ethically towards each of them, based on the principles above. The directors are people acting on behalf of a company or business, so they should consider all the stakeholders involved. The following internal stakeholders are involved: The shareowners (shareholders) or owners, The board and directors, The committees of the board, Management, Company secretary, The company or business itself, Internal audit, and The employees. The shareowners have shares in the company, for which they expect a good return on investment. They elect the directors, and in exchange they expect at least an annual report and other relevant communications. Some of the directors also have shares and are, therefore, shareowners as well. The board of directors appoints various board committees, for example the audit committee, for certain tasks and they expect regular reports from them. The directors appoint management and the company secretary to run the company on a daily basis. Management has to report regularly to the board of directors and also has to submit financial statements as part of the annual report to the board. Management manages the company and appoint employees. They are responsible to keep accounting records and have a good system of internal control in order to produce reliable financial statements. Management must work with purpose, according to certain values, in order to use the correct strategies to reach the company’s goals. Management has to be aware of risks for the business and must also identify opportunities. Furthermore, management has to prepare non-financial information, some of which has to do with corporate governance, and which also includes information that will form part of the annual report. Although management are responsible for all these functions, the final responsibility lies with the directors, which must ensure that accounting records are kept within a good system of internal control. They must ensure that reliable financial statements are produced which they are able to approve. They must determine the purpose and values of the company in order to determine the strategies to reach the company’s goals. The directors must identify all the business risks and opportunities. They must ensure that non-financial information is prepared and they are responsible to report on corporate governance in the annual report. In the final instance, the directors are in a position of trust and they are fully accountable to the company as a separate legal entity. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 5 The audit committee liaises with the external auditor and also review the plans and work of the internal audit department. The internal audit department audits accounting records and management reports and also audits efficiency and other non-financial information. This gives some assurance to the external audit that the system of internal control is working. It also gives assurance to the audit committee and finally the board that the company is well run and that internal control is working and that the information supplied is reliable. The internal audit department has to liaise with the external auditor. Central in the company is its purpose and values, from which the strategies are developed to reach its purpose. The above describes the company and its internal stakeholders as such. The external stakeholders are the following: The external auditor is one of the external stakeholders, who has to audit the annual financial statements of the company in order to express an opinion on the fair presentation of these statements to the shareowners. This is very important for the shareowners, as the external auditor is independent from the company and its directors and management. They have contributed capital to the company and they want to be assured that the financial information they receive is reliable. The shareowners appoint the external auditor at the annual general meeting. The external auditor relies on the work of the internal audit, and also liaises with the audit committee. The other external stakeholders are found in the following three environments: The community or communities in which the company is operating; Society in general – local, national and international; and Environmental and green issue stakeholders. The relevant external stakeholders involved in these three environments are: Potential investors who might become shareowners; Government (local and national); South African Revenue Services (SARS), who wants to receive taxation from the company; The investigative media; Ethical and green issue pressure groups; The public in general and other companies, as customers, clients or consumers; Suppliers; and Industry, partners and competitors. The company, and more specifically the directors, have a responsibility towards all these internal and external stakeholders. Through proper and knowledgeable guidance, the above can assist directors in recognising all their ethical responsibilities, even on a wider basis as required by the King II Code and good corporate governance in general. All the relevant stakeholders and their relationships can be graphically depicted as in Figure 2. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 6 A pp oi nt De ali ng s Aud it c om mit t ee Inte rnal External auditor an d se cu rit ies CEO audi executive and non-executive tor t audi Company itor a ud with strategies and goals Accounting records, Internal control and AFS Purpose and Values Potential investors Government and SARS Community Customers/ Clients/ Consumers Society Environment = Company and internal stakeholders = Other (external) stakeholders CEO = Chief Executive Officer SARS = South African Revenue Services ROI = Return on Investment Figure 2. The internal and external stakeholders of a company and their relationships (Du Toit 2002 as quoted by Du Toit 2007) The King II report (King Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa – 2002) was released and is published by the Institute of Directors (IOD) in Southern Africa in March 2002. This, as well as the large corporate collapses in the USA (and also in South Africa), have resulted in a renewed focus on corporate governance. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 7 3. Literature survey The literature survey provides a brief background on sustainability reporting and sustainability assurance. Literature on the competencies of the assurance provider is subsequently surveyed. 3.1 Sustainability reporting The 1990s saw a steady increase in companies and corporations reporting on social, environmental and economic dimensions (called the triple bottom line or TBL by Elkington (2004)) of their performance, partly due to reports like the Cadbury report in the UK and the King report in South Africa. Some sustainability reports were (and some still are) included in the financial reports or annual report, while stand-alone reports also started to emerge, carrying various descriptions like sustainability reports, CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) reports, social reports, environmental reports and corporate accountability reports (ACCA 2004; Du Toit 2007). The TBL is all about accountability, and these three dimensions are certainly included in the concept sustainability (Henriques 2004), which has become the latest accepted term in this regard. Sustainability reporting is about stakeholder reporting (reporting to stakeholders), which requires an integrated approach in which all stakeholders are taken into account (IoD 2002). There are internal and external stakeholders, as described in paragraph 2 above. The GRI (Global Reporting Initiative 2000-2006:5) defines sustainability reporting as the practice of measuring, disclosing, and being accountable to internal and external stakeholders for organizational performance towards the goal of sustainable development. King II (IoD 2002) states in its code the following about sustainability: Sustainability Reporting Every company should report at least annually on the nature and extent of its social, transformation, ethical, safety, health and environmental management policies and practices. Matters requiring specific consideration should include: Safety, health and environment (SHE). Society and transformation, incorporating black economic empowerment, gender and equity issues as matters of continuing strategic significance for South African companies. Human capital. Although this is a very small part of the code, the importance of sustainability is highlighted by the fact that sustainability is dealt with in 31% of the King II report (IoD 2002): 108 of the 354 pages deal with sustainability and the GRI. The most dominant reporting framework, guidelines and principles are those published by the GRI – these standards can be considered as generally accepted (Ballou, Heitger & Landes 2006). The latest are the G3 guidelines published by the GRI in August 2006. These GRI Guidelines are used voluntarily by organisations for sustainability reporting. According to KPMG (2005) 660 8 © Anton Du Toit, 2008 companies reported on the GRI basis in 2005. This number has now grown to 2 302 (GRI 2007). There is, however, increasing pressure for mandatory sustainability reporting. France, South Africa and Denmark are among the countries that require a degree of sustainability reporting as part of the stock-market listing requirements (ACCA 2004). Some of sustainability reports are independently verified in order to add credibility. This is done in an assurance statement. Of the G250 (the top 250 companies of the Global Fortune 500) 30% had assurance statements and of the N100 (the top 100 companies in 16 countries identified by KPMG) 33% had assurance statements in 2005 (KPMG 2005). The major auditing firms still dominated the assurance market in 2005, when 58% of all corporations surveyed by KPMG made use of major auditing firms and the rest made use of certification bodies, technical expert firms, specialist firms and other assurance providers (KPMG 2005). 3.2 Sustainability assurance Verification of environmental and social reporting is necessary for it to be credible. As in financial accounting, verification must be done by competent and independent auditors (or assurance providers) who are not involved in the production of the environmental and social accounts (UNCTAD 2004). According to Ballou, Heitger and Landes (2006), the quality and usefulness of a sustainability report may easily be reduced if no independent assurance report is added. Aspects of sustainability reports are auditable because they are quantitative and verifiable. There are, however, also many qualitative statements (for example, about risk management and performance) as well as quantitative measures that are not reliable enough to audit or that are not verifiable. The reports are, therefore, mostly limited in scope. The GRI Sustainability Reporting Guidelines embrace three different application levels for sustainability reports for corporations, titled as C, B and A, progressing towards a higher coverage of the GRI Reporting Framework from C to A. If external assurance on the report was obtained, a plus sign (+) can be added to the category (e.g. C+, B+, A+) (GRI 2000-2006). Although external assurance is not a mandatory requirement, it is recommended by the GRI. In the past few years, two global assurance standards have been released to guide the work of many assurance providers. These are ISAE 3000 (International Standard on Assurance Engagements 3000) and AA1000 (KPMG 2005). ISAE 3000 is published by the International Auditing and Accounting Standards Board (IAASB) of IFAC under the title Assurance engagements other than audits or reviews of historical financial information. This standard, which became effective for auditing firms as from 1 January 2005 (SAICA 2003), has to ensure that an assurance engagement is performed with professional rigour and independence (KPMG 2005). It accommodates both reasonable assurance engagements and limited assurance engagements (SAICA 2003). AA1000 is issued by one of the ‘other’ assurance bodies, called AccountAbility, based in the United Kingdom. 3.3 Competencies of assurance providers If one considers the levels of expertise of external auditors or auditing firms in the traditional financial attestation role (and professional auditors’ intense technical training and education in financial matters), doubt is raised as to the expertise or competencies of the auditing firms in producing sustainability assurance reports if expertise in the following fields is not present: Language and semantics. Non-financial information includes not only numbers, but also paragraphs of text. In multinational corporations, reports and interviews in various languages 9 © Anton Du Toit, 2008 are combined (consolidated) to produce the final sustainability report. If the auditor is to express assurance on these reports, he/she or someone in the team or firm (or external consultants) should have high-level language and translation skills. Historical data analysis. Traditionally, the auditor looks at historical data when a financial audit is performed (he/she is trained and educated in this regard). Sustainability reporting also includes historical data, but the word sustainability in itself means that a forwardlooking or predictive focus is present in such a report. The risk associated with assurance on reports trying, in part, to predict the future, is extremely high for the auditor wishing to be an assurance provider. This is more specifically true when the auditor is reviewing qualitative data as part of the assurance engagement. The various technical areas of environment, safety and health. Although this might seem like a short and simple requirement, the relevant expertise lies in the fields of many professional people like doctors, engineers, nurses and environmentalists. Taking the above into account, one should consider what is required in the currently available guidelines for assurance providers. Assurance providers must understand the business operations as well as the environmental and social issues of a reporting entity. This can be done by using multidisciplinary teams (UNCTAD 2004). Assurance should, therefore, be provided by competent groups or individuals external to the organisation (GRI 2000-2006). KPMG (2005) states that both AA1000AS and ISAE 3000 address some aspects of assurance quality, such as the need for appropriate knowledge and skills in the assurance provider, as well as the importance of independence. According to ISAE 3000 (SAICA 2003:paragraph 9): The practitioner should accept (or continue where applicable) an assurance engagement only if the practitioner is satisfied that those persons who are to perform the engagement collectively possess the necessary professional competencies. This is quoted directly because this paragraph contains the only sentence in the standard dealing with competencies. This requirement is supported by the FEE (Fédération des Experts Comptables Européens – the European Accounting Association) when it states that the assurance report is important and that users (readers) should be informed about the independence of a practitioner and how the practitioner has sufficient competence for issuing the assurance report (FEE 2006). This can be clearly interpreted as a need to disclose the practitioner’s competencies. As stated in the introduction, these required competencies are, however, very seldom listed or properly described in the literature. Performing a literature search does not produce many results, even in ProQuest, ABI/Inform and other authoritative databases (altogether covering literally hundreds of databases). The documents found are summarised below: AccountAbility’s AA1000 Assurance Standard (2003). AccountAbility is widely recognised globally, as is evident from the majority of assurance reports referring to AA1000 and the fact that almost all recent literature and research give authority to AccountAbility. The Criteria for Certification as a Sustainability Assurance Practitioner, issued in January 2007 by IRCA, is a major document and quite comprehensive with regard to competencies of assurance providers. IRCA is the International Register of Certificated Auditors, which operates in partnership with AccountAbility. Another partnership between AccountAbility and the international accounting body ACCA (The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants) resulted in an excellent research report (ACCA 2004) called ‘The future of sustainability assurance’. Some references to competencies are found in this report. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 10 The only doctoral thesis found covering competencies very briefly, is the thesis of Melvin Joseph Wilson (2003) for his Doctor of Philosophy studies at the University of Calgary in Alberta. The title of the thesis is ‘Independent assurance on corporate sustainability reports’. Five research papers were found. Two of the five papers were produced by the same authors, the latest one of the two giving updated data compared with the earlier one. The dates of these papers range from 2004 to 2007, but some of them deal only with the disclosure of competencies in actual sustainability assurance reports, and not with the competencies themselves. IRCA provides a professional qualification in sustainability assurance. As the qualifications (there are various levels) are based on experience and competencies, IRCA had to describe them. Two of the aims of the Sustainability Assurance Practitioner programme of IRCA are to do the following (IRCA 2007:4): Enable practitioners to develop, validate and communicate their competencies in a systematic manner; and Develop a more systematic understanding of key competencies for providing effective assurance. IRCA (2007) asserts that it has been particularly difficult to define the technical competencies and explains that the competencies stated will continue to evolve from one year to the next. IRCA also acknowledges individuals’ experience in the field as part of the certification process. This indicates that this area has not yet been properly researched. As the purpose of this study is to explore reports of auditing firms, it is appropriate to look at the ‘Lead Sustainability Assurance Practitioner’ and his/her competencies, and not at any lower level of IRCA certification. The audit firm should have at least the same level of competencies. The required competencies are explained in detail below. They are listed as in the IRCA (2007) document and the other literature findings are linked to them in Table 1. References are provided in the first row. The IRCA competencies are quoted directly in the first column in order to avoid bias or free interpretation when compiling the table, and the other literature is provided in columns two to four. Table 1. Competencies of assurance providers as summarised from authoritative literature sources IRCA (2007:7) ‘An understanding of Sustainability Assurance, including accounting and data review procedures and auditing practise.’ AA1000AS (AccountAbility 2003:2729) Individual: Professional qualifications Organisation: Adequate assurance oversight taking assurance to the highest possible standards. Also: understanding the legal aspects of assurance, and having adequate professional indemnity insurance Also: infrastructure for secure, long-term storage © Anton Du Toit, 2008 ACCA report (ACCA 2004) Wilson (2003) Technical competencies and orientation: General assurance competency. In terms of sustainability, all the big 4 audit firms are strong in this regard. Knowledge of the assurance standards and processes 11 ‘An understanding of and ability to apply and to embed techniques and processes of stakeholder engagement and to assess and assure against these principles.’ of assurance-related material. Individual: Ability to consider stakeholders is only mentioned. ‘An overall understanding of sustainable development encompassing: Social and ethical issues Environmental issues Economic issues’ Individual: assurance experience in social and ethical, environmental, economic and financial assurance. Also: area of expertise covering key dimensions of the information provided. ‘The ability to make informed professional judgements on an organisation’s sustainability performance…’ Organisation: ‘Assurance work is required by one or more mechanisms or processes, such as an Assurance Committee, involving people neither undertaking nor directly benefiting from the Assurance work in question.’ Process competencies: Identify and communicate with stakeholders, determine materiality and assess the quality of responsiveness and completeness. Typically market researchers and assurance consultancies. Substantive/ content competencies: Understand the wide range of social, scientific, economic and industrial issues. Less often suitable criteria for social and environmental performance – more risky than financial assurance. Judgement of the assuror is crucial, leading to either a reasonable level or limited level of assurance. No individual or organisation possesses all the competencies mentioned above. A solution is the use of teams or advisory panels of experts. Knowledge of environmental and social issues Attitudinal criteria: objectivity and independence. (This is an interesting one, not included in the scope of this paper, but nevertheless listed as a kind of competence or quality by Wilson.) The kind of skills or competencies needed is also referred to in papers about social auditing – there is a concern that financial auditors offer technical skills for a social audit focused on corporate management issues, but they do not automatically possess the skills to enable them to incorporate the views and values of stakeholders. Some authors even talk about an assurance expectation gap and others do not think that the financial auditor’s objectivity has a place in social auditing. This has been summarised by Boele and Kemp (2005), who actually propose a hybrid approach to social auditing, combining subjective and objective data, and that social auditors could learn from financial auditors, and vice versa. Language skills or competencies are not mentioned once in the literature that sets out the competencies mentioned in Table 1. In an paper on social auditing, Boele and Kemp (2005) state that social auditors should be multilingual. They then argue that social auditors need to communicate with different people from different cultures, where ethical, cultural and social complexities are present. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 12 The competency to be able to predict the future within certain parameters is also not mentioned. Applied mathematics is a core competency of economists, enabling them to do just that. The last part of this literature survey is an elaboration of the IRCA competencies listed in Table 1. The competencies, as well as the qualification, training and experience route that forms the certification criteria for Lead Sustainability Assurance Practitioner of IRCA are more fully discussed. (There is another route of pure experience, but that simply states various numbers of years of experience for the various areas, ranging between two and four years). Table 2 below contains the relevant information. Table 2. Competencies and certification criteria for the Lead Sustainability Assurance Practitioner grade (IRCA 2007:22-23) Competency area An understanding of sustainability assurance, including accounting and data review procedures and auditing practice: ‘Assurance: Well-established understanding of and ability to apply, embed, assess and assures against principles and process standards of the AA1000 Assurance Standard. Well-established understanding of the level of assurance required by the organization and its stakeholders. Ability to lead a multi-disciplinary team and take the lead in preparing assurance statements. Audit procedures and techniques: Well-established understanding of and ability to audit information and information systems and internal controls and to apply and embed internal and external audit principles, procedures and techniques, including a variety of audit methods as appropriate: financial, ethical or environmental management systems etc. including surveys, expert reviews, methods of stakeholder engagement, etc. Ability to plan and assess an internal audit of an organization’s relevant processes appropriate to: The size and complexity of the organization The scope of the audit The organization’s activities, impacts and stakeholders. Ability to report the audit and formulate an appropriate audit report (including findings, conclusions and recommendations) to the organization’s governing body or management. Accounting procedures and techniques/Data assurance: Well-established understanding of and ability to apply and embed accounting/ data accuracy principles, procedures and techniques pertaining to economic and financial, social and environmental issues.’ ‘Stakeholder engagement: Well-established understanding of and ability to apply © Anton Du Toit, 2008 13 Certification criteria: Qualification, training and experience route 1. ‘Relevant Assurance Training (3 day minimum), covering the significant elements of sustainability assurance courses acknowledged by AccountAbility … or equivalent.’ 2. ‘At least 3 years relevant experience leading a multi-disciplinary team in an Assurance Assignment, which includes the analysis and/or implementation of audit and accounting procedures and techniques in assurance. 3. At least one year’s experience in taking the lead role in preparing Assurance Statements.’ 4. ‘One of: A financial accounting qualification awarded by established institutes such as ACCA or equivalent’ ‘or A management systems lead auditor qualification, including any grade of IRCA auditor certification, IEMA auditor certification or equivalent.’ ‘or Relevant training focusing both on the auditing and accounting requirements as referred to within the left column.’ ‘or Relevant on-the-job training at work covering the intent and application of accounting/data system review principles/auditing principles, procedures and techniques relating to economic and financial, social and environmental issues.’ 5. ‘Relevant training on stakeholder engagement covering the questions and to embed techniques and processes of stakeholder engagement and to assess and assure against principles.’ ‘Sustainable development: Well-established understanding of sustainable development encompassing: Social and ethical issues Environmental issues Economic and financial issues.’ ‘Demonstrate ability to make informed professional judgements on the quality and robustness of an organization’s stakeholder engagement and assurance processes in place and an organization’s sustainability performance.’ ‘why’, ‘how’ and ‘so what’ including training acknowledged or organized by AccountAbility. 6. At least 3 years relevant experience, which includes the analysis and/or implementation of stakeholder engagement in assurance.’ 7. ‘Expertise in all 3 dimensions of sustainability development through training, attendance of workshops etc. (at least 7 days in the last 3 years in total)’ 8. ‘At least 3 years relevant experience across the three areas of sustainability development.’ 9. ‘Personal statement outlining your understanding of sustainability development.’ 10.‘Mandatory interview to evaluate your ability to apply informed professional judgement on an organization’s sustainability performance.’ The above literature survey shows that the most obvious route for an assurance provider would be to disclose in his/her assurance report whether he/she is registered as a Lead Sustainability Assurance Practitioner and whether the other members of the assurance team are registered with IRCA at any level. This will automatically give credibility to an assurance report, as a certain level of qualifications, training and experience would then be implied. The objective has been reached, to determine which competencies an auditing firm should possess as an assurance provider. 3.4 Thinking skills In the above analysis in paragraph 3.3, the competency areas required by the assurance provider include a general assurance competency (including the ability to audit and to apply audit principles), as well as the ability to make informed professional judgements on an organisation’s sustainability performance. This basically comes back to the external auditor’s ability to audit financial statements and to express an opinion thereon. The basis of proper auditing is pure analytical and critical thinking processes, which can be summarised as logic or the ability to think logically. Currently the closest training or education of an auditor or accountant in “logic” is the subject Mathematics. No training, education or exercise in Logic is part of the syllabi of the auditor and accountant. Du Toit (1995) has developed a course on audit thinking skills, with the theory based on the work of Rossouw (1993). The following are highlights from this course: Logical skills or thinking skills fit the audit process perfectly. Good thinking habits also assists one to make better decisions in general. Each person makes hundreds of decisions every day and it is, therefore, important to be quite familiar with the decision-making process. Exercising professional judgement in an audit actually means nothing more than experience in the process of logical audit thinking. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 14 Audit thinking skills are the skills to think properly during an audit. To be able to think properly requires logic: analytical and critical thinking. Logic is the study of the logical thinking processes in order to reason (argue) properly. In order to think logically, there are certain techniques one should master. The essence of both Auditing and the audit process is logical thinking. In the 16th century, the name for an auditor in Italy was rasionele — the auditor was, therefore, regarded as a rational person. There is no other subject area describing Auditing better than logic. For this reason, logic is very important for the auditor – the two cannot exist separately. It is important to notice that knowledge and logical thinking forms insight or wisdom – the ability to take wise decisions, which comes from regular exercise in logic, based on the relevant and required knowledge. During the audit process the auditor must collect audit evidence enabling him/her to express an opinion on the fairness of the financial statements. He/she must, therefore, reach a conclusion based on certain facts/evidence. If the auditor erroneously accepts or rejects audit evidence, the auditor has made a thinking mistake. In order to evaluate conclusions (arguments) one needs certain thinking virtues or good thinking habits: Patience and intellectual tolerance; Fairness – listen to all the facts before making a conclusion/expressing an opinion; Be honest about one’s own prejudices; The willingness to analyse: distinguish things and separate them. This is very important; Compare things – get the logic context and systemise; Try to do it in other ways – do experiments; and Thoroughness and persistence. Logical thinking is about reasoning abilities. It is about the distinction between good and bad reasoning. Logic thinking is both an art and a science. As a science, it investigates, develop and systemise principles and methods that can be used to make this distinction. As an art, logical thinking can be seen as logical abilities or thinking abilities, related to certain skills. These skills can be applied to: Solve problems; Evaluate evidence; Provide evidence; Argue; Analyse a problem in its components; Detect errors in reasoning or in an argument; and Understand issues and modern day problems and to form an opinion about them. The technique to improve the thinking process and proper analysis, is to ask questions to break down the problem in its basic elements. These six questions are: What is the question or problem? What is the objective or solution? What do the important concepts mean? What are the important facts? What is the implications or consequences? 15 © Anton Du Toit, 2008 Can it be done in another way? The next step is to use all these skills, techniques and qualities to construct arguments, to form opinions, to express opinions and to reason. An argument is used to convince other people. An argument consists of two parts: Reasons (called premisses); and A decision (called a conclusion). To build or construct good arguments, there should be good reasons for the argument. Reasons should comply with two requirements: Each reason must be true, relevant, reliable and valid; and The more reasons there are for an argument, the better is the argument. To convince someone else, one should, therefore: Give many reasons; and Make sure that there is proof for the reasons. In the same manner, one would dispose of the arguments of other people by pointing out an irrelevant, invalid or false statement, or by providing more reasons for the opposite point of view. In order to have a proper argument and to properly analyse facts (and reasons), there are certain problems regarding concepts or ideas which one should avoid/treat carefully: Ambiguity; Vagueness; Obscurity; and Emotive words. One of the most important rules to remember while auditing, is to think and link. One must find links (similarities and differences) between issues. The question, therefore, with regard to any piece of information one encounters, is: "How does it relate (link) to the things I know already?" As stated above, reasons (premisses) lead to a decision or conclusion, meaning in a argument the following sequence is true, as set out in Figure 3. Reasons (premisses) Decision (Conclusion) Figure 3. Reasons lead to a decision (Du Toit 1995) The audit process consists of the accumulation of audit evidence which leads to an opinion about the fairness of the financial statements. Audit evidence is, therefore, the same as the reasons (facts) in a logic argument. An opinion is, therefore, the same as the decision or © Anton Du Toit, 2008 16 conclusion of an argument. Audit risk is considered throughout the whole process. The sequence is then as set out in Figure 4. Items of audit evidence Audit opinion (considering audit risk) Figure 4. Audit evidence leads to an audit opinion (Du Toit 1995) All the audit opinions about each assertion (like the existence of inventory) leads one, in the end, to a final audit opinion about the fairness of the financial statements. In the end, an audit is the accumulation/collection of audit evidence in order to express an audit opinion with as little audit risk as possible. To perform better audits, logic must be applied during the whole audit process, in making use of the audit trail to audit, and logic must be reflected in the audit working papers and audit files. The above process is just as valid for providing sustainability assurance. 4. Conclusion and recommendations The field of sustainability assurance is relatively new, as is evident from the results of the literature survey. The literature survey has shown that not nearly enough literature (and underlying research) is available on the competencies of teams of assurance providers. Some competencies like language and semantics skills and the ability to use mathematics or econometric models to assist in predicting the future have not yet been explored even at grassroots level. Based on the findings of the literature survey the following conclusions are made: At present, no minimum standards are determined or required for the competencies of auditing firms performing sustainability assurance engagements. Very little research has been done on the nature, depth and minimum levels of competencies required by the assurance provider, more particularly so for the auditor and auditing firm. Almost no literature could be found on the language skills required for a sustainability assurance engagement. Almost no literature could be found on the logical skills of auditors. Very little mention is made of competency to be able to predict the future within certain parameters. As stated before, many auditing firms have not yet become familiar with the latest issues around sustainability reporting and their competencies to provide assurance are rarely disclosed. Expectations are created for the readers of the reports, and although many assurance reports limit its liabilities to its client only, it would be in the best interest of corporate governance and sustainability reporting to correct some of the issues raised. The recommendations that follow are an attempt to rectify the situation: Auditing firms should ensure that they do have the competencies and expertise available in assurance teams. Particular attention should be given to competencies regarding stakeholder © Anton Du Toit, 2008 17 engagement and sustainable development (social, environmental and economic) as displayed in Table 1; as well as language skills and logical skills. Auditing firms should be careful in being associated (by providing assurance) with predictions and any future intentions of clients. Assurance providers should be extremely careful in performing full audits (reasonable assurance provided) of sustainability reports. Staff of auditing firms involved in sustainability reporting and assurance thereof, should preferably be registered at IRCA and the head of the team or partner/director in the firm should be registered as a Lead Sustainability Assurance Practitioner. If this fact is disclosed in the assurance reports, it should ensure that any reader of assurance reports would be able to see which competencies they possess, as it is clearly defined by IRCA. Should auditing firms not wish to go this route, IFAC should start to define the competencies in a document like ISAE 3000, or in its successor. Training and education providers (and auditing firms providing on-the-job training) in the auditing and accounting field should reconsider their syllabi to reflect some of the competencies and thinking skills required. It is important that auditors’ thinking skills are developed more intensively. The outcomes for the learner or student or should be to (Du Toit 1995): Be familiar with the use of good thinking habits; Be able to master a good thinking process; Be able to analyse arguments (reasoning) properly and to come to sensible conclusions; Be able to identify the audit principles logically, to analyse them and to criticise them; and Using the above, be able to perform more logical, effective and sensible audits on both financial and non-financial information. Assurance reporting is still in its infancy and much more research and development of this new area are needed. This paper also opens the following research opportunities: An empirical survey of at least the big 4 auditing firms in the competencies they actually have when issuing an assurance report. The competencies regarding language and semantics need to be researched. The thinking skills and competencies need to be researched. The competencies required about involvement with statements about the future should be researched. Sustainability in itself implies the future. Development of a framework of competencies for auditing firms in sustainability assurance. This framework could later become part of a standard. This could include a critical evaluation of IRCA’s framework and should also consider language and “future” skills as mentioned above. Research into the technical competencies required to be involved in environmental, social or economical sustainability assurance. Much can be learned from other assurance providers like consultants and teams of experts, and research should be done on this topic as well. To conclude, the auditing profession should consider its role in society, whether to remain the financial-only experts or to widen its scope to provide assurance on sustainability and on corporate governance. If the second choice is made, the training and education requirements for auditors should be revisited and redesigned. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 18 Bibliography ACCA (Association of Chartered Certified Accountants), 2004: The future of sustainability assurance – ACCA Research Report No. 86. London: ACCA & AccountAbility. AccountAbility, 2003: AA1000 Assurance Standard. London: Institute of Social and Ethical AccountAbility (AccountAbility). Ballou, B, Heitger, DL & Landes, CE 2006: The future of corporate sustainability reporting, a rapidly growing assurance opportunity. Journal of Accountancy, 202, 6: 65-74. Boele, R & Kemp, D 2005: Social auditors: illegitimate offspring of the audit family? The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, Spring 2005, 17: 109-119. Du Toit, A 1995: Audit thinking skills. Randburg: PROS Training. Du Toit, A 2007: Corporate governance. Business management for accounting students, 2nd edition, eds Nieman, G & Bennett, A. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. Elkington, J 2004: Enter the triple bottom line. The triple bottom line – does it all add up? Eds Henriques, A & Richardson, J. London: Earthscan. FEE (Fédération des Experts Comptables Européens), 2006: FEE Discussion paper – key issues in sustainability assurance – an overview. FEE, June 2006. GRI (Global Reporting Initiative), 2000-2006: RG - Sustainability reporting guidelines. Amsterdam: GRI. GRI (Global Reporting Initiative), 2007: reporting search engine on the Internet: url: http://www.corporateregister.com/gri/, accessed on 14 July 2007. Henriques, A 2004: CSR, Sustainability and the triple bottom line. The triple bottom line – does it all add up? Eds Henriques, A & Richardson, J. London: Earthscan. IoD (The Institute of Directors in Southern Africa), 2002: The King report on corporate governance for South Africa - 2002. Parktown, South Africa: The Institute of Directors in Southern Africa. IoD Bulletin, 2007: Corporate governance: King III on the cards. Parktown, South Africa: The Institute of Directors in Southern Africa IRCA (International Register of Certificated Auditors), 2007: Certification as a sustainability assurance practitioner. London: International Register of Certificated Auditors. KPMG, 2005: KPMG international survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2005. Amsterdam: KPMG. Payne, N 2002: Leadership with Integrity. Accountancy SA, SAICA, January 2002. Rossouw, GJ (Red) 1993: Dink vaardig. Revised edition. Pretoria: RGN publishers. SAICA (South African Institute of Chartered Accountants) 2003: ISAE 3000 - Assurance engagements other than audits or reviews of historical financial information. Handbook 2007. Johannesburg. UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) 2004: Disclosure of the impact of corporations on society – current trends and issues. New York & Geneva: United Nations. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 19 UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) 2006: Guidance on good practices in corporate governance disclosure. New York & Geneva: United Nations. Wilson, MJ 2003: Independent assurance on corporate sustainability reports. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Calgary, Alberta. © Anton Du Toit, 2008 20