Paper - Saide

advertisement

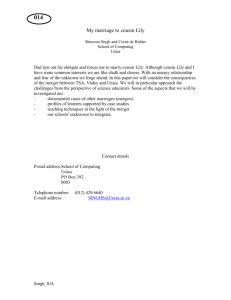

A student-centred approach: Incorporating students characteristics in the development of the support services Dr Mpine Makoe Institute for Open and Distance Learning University of South Africa Abstract: Increasing access to higher education can only be successful if distance education providers understand the varying contexts and experiences of their students in order to develop support mechanisms that are responsive to students’ needs. A better understanding of student needs could assist distance education policy makers, course designers and developers, lecturers and tutors, to develop support systems that are student-centred and capable of addressing their needs directly. The purpose of providing student centred support services is to ensure that students derive maximum benefit from the whole experience of being a student. This paper provides an overview of the literature on student centredness and student support in ODL. Using University of South Africa (UNISA) as a case study, it seeks to clarify what constitutes student support in the UNISA context. Understanding of students’ prerequisite knowledge, their learning environment and their cultural attributes are starting points in the development of the student-centred support services (Anderson, 2008). In this paper, the characteristics of students are going to be used as a guiding principle for developing an effective student-centred support services. Keywords: Student support; Open distance learning; University of South Africa; student-centred approach 1 A student-centred approach: Incorporating students characteristics in the development of the support services Introduction For distance education to be successful, student support services should be truly student-centred. By this we mean that, distance education institutions need to recognise and understand the varying contexts and experiences of their students in order to develop support mechanisms that are responsive to students’ needs. A better understanding of student needs could assist distance education policy makers, course designers and developers, lecturers and tutors, to develop student support systems that are student-centred and capable of addressing their needs directly. Pulist (2001) referred to studentcentred approach as a paradigm shift in terms of students being seen in control over their learning. It aims at developing in each student a sense of responsibility for his or her own learning by focusing on individual student’s experiences, perspectives, background, interests, capabilities and needs. It is important therefore to take into account diverse variables of students’ needs, the educational ethos of the institution and the differences within the student body when developing student support system (Sewart1993). An effective student support service in distance education is characterised by responsiveness to students’ needs, that is, it personalises the learning process; it encourages and facilitates interaction between students and stakeholders; it facilitates learning within courses and “it evolves continuously to accommodate new learner populations, educational developments, economic conditions, technological advances and findings from research and evaluations” (Brindley and Paul 2004, 45). Sewart (1993) suggests that student support systems must be constructed in the “almost infinite needs of the clients; should be dependent on the educational ethos of the region and 2 the institution; also dependent of the dispersal of the student body, elements of resource and curriculum … which has been set up to serve” (12-13). This shows that there is growing support of focusing on the students and what they bring in the learning environment. The purpose of providing student centred support services is to ensure that students derive maximum benefit from the whole experience of being a student. This paper provides an overview of the literature on student centredness and student support in ODL. Using University of South Africa (UNISA) as a case study, it seeks to clarify what constitutes student support in UNISA context. UNISA was chosen as a case study because it is a dedicated comprehensive distance education institution in South Africa. The aim is to identify the principles that guide the planning of student support services that is student centred. Understanding of students’ prerequisite knowledge, their learning environment and their cultural attributes are starting points in the development of the student-centred support services (Anderson, 2008). In this paper, the characteristics of students are going to be used as a guiding principle for developing an effective support service for students studying at a distance. Distance Education Distance education institutions have been instrumental in developing support services that will assist their students to perform better. The focus on providing student support services were driven by the need to address the high drop-out rates that were associated with correspondence education (Rumble, 2000). In correspondence education, distance education students receive study material - sometimes only a wrap-around to a textbook which they must purchase separately, and their next engagement with the institution is when they sit for the examination (Glennie and Bialobrzeska, 2006). This system assumes that students have the ability to work through the study material independently. However, studies have shown that students seem to value contact with other people even when they study at a distance (Rumble 2000; Sewart 1993; Tait 2003; Thorpe 2001). 3 One of the major challenges facing distance education institutions is to provide support for “isolated students who are left to fend for themselves,” (Brindley and Paul, 2004, p.40). In distance education, students are physically, emotionally and socially separated from the institution. Moore (1993) defines this distance in terms of the responsiveness of an educational program to the student rather than in terms of the physical separation of the instructor and the student. He argues that distance education, not only a geographic separation between the teachers and the learners, is a pedagogic concept. This separation affects the patterns of teacher and student behaviour. In this separation there is a “psychological and communications space to be crossed, a space of potential misunderstandings” between instructors and students who are physically separated (Moore, 1993, p.22). It is in this space, that Moore describes as transactional distance, where the structure of the educational program and the quality of the interaction between the teacher and the student determines academic performance. This challenge of isolation which has been associated with correspondence nature of distance education is even more acute in places of limited resources such as rural South Africa. Students studying through distance education are not only geographically isolated from their teachers as sources of information and separated from their peers as sources of support. The effects of such isolation on distance learners can inhibit any possibility for engagement with teachers, study material and peers (Simpson, 2002). Studies have shown that proper provision of student support services may break learners’ isolation and meet not only the academic demands of students in distance education but also their social needs (Brindley and Paul 2004; Rumble 2000; Tait 2003; Thorpe 2001). The student-centred approach In order to support distance learners effectively, lecturers in distance education need to be aware of the variations of experiences that students bring into the learning environment. They need to understand who their learners are, where they are coming from, what type of support is needed and how best could they help in facilitating the learning process. This could 4 be achieved through acknowledging the role of the student in the learning process. Once we know who our learners are, it becomes easier to look at the support mechanisms that we can provide to our learners. This support should be student-centred in order to address the needs of distance education students. Student centred approaches is a method of learning and teaching that puts the students at the centre (Beheler, 2009; Knowlton, 2000) This approach has major implications for the design and development of the study material, the learning processes, the assessment practices and the support services in distance education. In distance education, teaching is predominantly mass-produced printed study material with some integration of technologies such as radio, television, audio and video cassettes, computers and computers. Most of the study material are designed from the teacher centred approach which focuses on the lecturer who decides on the knowledge that is worthy of being studied. In the teacher centred approach, according Knowlton (2000) the “the professor is a giver of knowledge –the waiter or waitress who fills the empty glass …. (and) the students are an empty glasses waiting to be filled so that they can contain knowledge worthy of dissemination” (p.7). This view that is usually behaviourist in nature is often manifested in study material. In the behaviourist view, learning is a function of change in behaviour as a result of an individual's response to events that occur in the environment (Dahl, 2003). They defined learning as a sequence of stimulus and response actions in observable cause and effect relationships. In criticising the behaviourist theories, Piaget, whose theories mark the beginning of constructivist theory, argued that asserted that learning can only be understood from the learners’ point of view (Dahl, 2003) . He criticized behaviourists’ theorists for focusing on the idea that knowledge is separate to the human mind and that it must be transferred to the learner in a teacher centred approach (Bruner, 1996). He believed that students should be active participants in the learning environment. Constructivists base most of their 5 research on how the learner selects and transforms information, constructs hypotheses, and makes decisions, relying on a cognitive structure to do so (Bruner, 1996). This theory forms the bases of student centredness approach by viewing learning as an active process. Vygotsky’s (1930/1978) main criticism of Piaget is that thinking develops from the social level to the individual level (Dahl, 2003). He suggested that knowledge is constructed in the social context before individuals can make sense of it. Vygotsky’s (1930/1978) believed that people use cultural practice in which they are engaged by tailoring it to serve particular, practice-linked cognitive function. In his sociocultural theory of cognitive development, Vygotsky (1930/1978) argued that knowledge acquisition is socio-historical and a cultural process. The dynamic relationship between culture, history, interpersonal interactions, psychological development and the important role of language are central to Vygotsky theory. He focused on the connections between people and the cultural context in which they act and interact in shared experiences. Vygotsky’s view of learning is in line with student centredness. McCombs and Whistler (1997) defines student centredness as: the perspective that focus on individual learners-their heredity, experiences, perspectives, backgrounds, talents, interests, capacities, and needs-with a focus on learning-the best available knowledge about learning and how it occurs and about teaching practices that are most effective in promoting the highest levels of motivation, learning and achievement for all learners. It is therefore important that distance education institutions and lecturers recognise the varying context of their student in order to put in place support mechanisms that are student centred in nature as opposed to teacher centred approaches. In the teacher–centred approach, lecturers dispense knowledge to students who have to respond to knowledge given. In a student-centred approach, students are active participants who bring with them a rich array of prior experiences, knowledge and beliefs as they 6 construct new knowledge and understanding (Knowlton, 2000; Beheler, 2009). The problem of learning in distance education becomes more critical when interaction between a lecturer and a learner is not as constant as that which exists in a conventional face-to-face situation. In correspondence education, the educational process is usually reduced from a dialogue to a monologue where a teacher sends out study material to the students. The assumption is that distance learners, do not need mediation or support as they go through their study material. Thorpe (2001) argues that “course materials prepared in advance of study, however learner-centred and interactive they may be, cannot respond to a known learner” (p.4). Central to student support is a mediated conversation between the students and the teacher through integrated and structured dialogue in the study material and in other interventions aimed at formative development of a student. This paper therefore argues for a student’s centred approach that will address some of the problems encountered by distance education students. The table below shows the differences between the student centred approach and the teacher centred approach. Approaches Student-centred Teacher-centred Construct their own Centre of knowledge knowledge with the Transmission of information assistance of the lecturer from a knowledgeable Discovery and independent individual to a student learning Dominant Constructivist and Behaviourist or Positivist theory sociocultural Processes Personalised and Directs and controls the individualised responses learning processes Collaboration and dialogue One-way communication among students and lecturers from lecturer to students 7 Process-oriented instruction through study material that focuses on authentic Study, memorise and mirror tasks and problem solving the correct view strategies Roles Students are active Students are passive Lecturer is a facilitator, Lecturer focuses on the coach, mentor and a content – sylabbi; discipline resource person based Students are responsible and accountable for their learning The concept of student support The importance of the student centred-approach in the development of the effective student support system is based on principles of active and engaged learning. Thorpe (1995) describes student support as “elements of learning capable of responding to a known learner or group of learners, before, during and after the learning process” (p.201). This definition describes the cross-functional, interactive, responsive, and individualised nature of learner support (Brindley and Paul 2004). Sewart (1993) equates student support services with service oriented programme where the students’ needs as customers are paramount. Tait (2000) described student support services in terms of the inquiry, advice, admission services, tutorials, counseling, study and examination centres in ODL. All these resources serve to support students’ cognitively, affectively and systematically (Tait, 2000, p. 289). Simpson (2001) describes student support in terms of its activities beyond the production and delivery of course material. He divides student support services between academic and non-academic support. Academic support is concerned with developing cognitive and learning skills whereas the nonacademic support deals with the affective and organisational aspects of 8 students’ studies. The purpose of student support in ODL is to meet the needs of all learners (Thorpe, 2001). The challenge of UNISA, the oldest and the biggest distance education institution in Africa, is to identify student support services for its over 300 000 students. UNISA has a network of community learning centres that provide tutorial support, counselling services and peer-group support. These centres provide a place where people can meet, attend classes and discussion groups, study, pick up books and other materials for learning. Where it is not possible to offer face-to-face tutoring, tele-tutoring (telephone, video, computer-conferencing) with lecturers is also used as well to support a twoway communication between the teacher and the learner. Tele-tutoring is utilised to reduce student’s sense of isolation because it can overcome geographical barriers and provides immediate discussion and feedback. Several technologies, such as UNISA’s Learning Management System, MyUnisa, have also been used to provide interaction and resources that supports all areas of teaching and learning. The multimedia approach that UNISA uses is much more effective than using one method of delivery. Despite well-meaning efforts of distance education providers, students especially those from disadvantaged environments still find it extremely difficult to adjust to and succeed in distance education. The present landscape of education in South Africa could not escape the prevailing political, economic and social factors of its creation. There are distinctive social conditions that precede and accompany the student as he or she enters higher education. These are student characteristics, enabling inputs and outcomes, the social, political and economic environment. All these elements can only be understood if the social context in which learning takes place is investigated. That is, how do students perceive and respond to the demands of their learning context? If we ignore the contextual concepts of learning, our attempts to enhance learning through providing appropriate support services will not be successful. 9 An effective student support services should be built around six core elements according to Tait (2000): (1) Student characteristics; (2) Technological infrastructure; (3) Course or programme demands; (4) Scalability; (5) Geography and Management systems. Although Tait identified six elements, this paper will focus on the UNISA’s student characteristics in order to understand their needs. “Identifying and understanding the implications of such needs requires prior knowledge about the characteristics of the student body as a whole” (Rumble, 2000, p.221). Tait (2000) asserts that the characteristics of the student body are critical and central to the development of an effective student support system. Characteristics of Unisa students: The main elements of student characteristics as proposed by Tait (2000) should include gender, age, domestic situation, nature of employment or unemployment, disposable income, educational background, geographical situation, language, ethnic and cultural characteristics. Rumble (2000) argues that the information about the students characteristics should not be based on aggregated data, but should consider the context in which learning takes place. Data from both qualitative and quantitative methods was deliberately drawn from black distance learners because studies have shown that this group find it difficult to cope academically in distance education. Qualitative data was collected from 60 black undergraduate students from township areas around the main campus of UNISA and 20 who came from remote rural areas in South Africa (Lephalala and Makoe, 2007). A questionnaire was also used to collect data from 630 students who attended discussion classes at UNISA, however, the analysis is based on 352 students (56%) who returned the questionnaire. Participants are representative of the marginalised students which is in line with current legislation on widening student participation, higher education institutions are expected to accommodate. These students are first generation university attendees in their immediate families or communities and they come from families where parents are either semiliterate or illiterate 10 Age demographics Headcounts 160000 140000 120000 100000 80000 60000 40000 20000 0 <24 25-39 40-49 >50 Figure 1: Age demographics of UNISA students in 2009. Data collected quantitatively revealed that a majority of students who participated are in the study were in 18-25 age group (57%) even though this age group accounts for 28% of the total headcount. The average age of UNISA students is 31.2 years. For many years, distance learners have always been presented as adults who are fully employed, who are often at a geographic distance from the campus and who pursue their study part time. Recently, there have been changes in the demographics of the distance learners. UNISA has seen a growing number of younger distance learners who are studying full time and most of them have never worked. In most Western countries, distance learning has become attractive to younger students because it offers flexibility. However, in South Africa, younger students enrol in distance education institutions because the tuition fees are much lower than on contact-based institutions. In the past, most students who enrolled at UNISA were those who were geographically separated from the institution; now most younger students leave their homes in rural areas to find rented accommodation in the vicinity 11 of the main campus, Unisa Mucleneuck Campus in Pretoria. These students who call themselves “full-time” students move closer to UNISA in the hope that proximity to the university would enable more help with their studies. This has become a dilemma for the institution because now students require a study area for daily use and also expect lecturers to attend to them on demand and on a daily basis. For these students learning is contextualised in terms of daily access to facilities like study areas, the library, lecturers and other students in the vicinity. The support services have to take into cognizance the changing landscape of ODL institutions while not neglecting majority of mature students. . Gender issues Unlike younger students who could move from their rural homes, most mature students especially women do not have the luxury of relocating. Women in rural areas are expected to spend most of their time doing household duties and attending to community needs and in Tumi’s case attending to duties that are usually performed by the women in her agegroup, who have left children behind to work in urban areas. Tumi1: In these communities you are expected to be a mother, a nurse, a social worker to the children you teach, and this is over and above being their teacher. So you can imagine how much time do I have left after attending to all these …. I’m left with very little time to attend to my own schoolwork. These added responsibilities leave very little time for studying as Mapule who together with her husband are students at UNISA found out that: Mapule: When we both come back from work, he goes straight to his desk to study while I prepare supper, iron children’s clothes, help them with their homework … you know how it is like here … he just do his 1 All names have been changed to protect participants’ identity 12 studies while I’m busy with household chores. No wonder I’m so behind with my school work. This problem of juggling responsibilities is not only unique to South African distance learners, the women in May’s (1994) study concluded that distance study “isn’t for everyone” and it is a significantly different experience for female students than it is for male students. It is therefore important that the student support system is structured in such a way that it helps students like Mapule and Tumi. Geographic issues The geographic distance and physical setting in which learning takes place affects students’ participation in the learning environment. Students from both rural and urban areas felt that they were not only physically cut off from the institution, but were also socially deprived from actively participating in the learning environment. Most students from rural areas reported that the geographic distance was a major problem. Lucas: I wish I was living much closer to the university, that way I could … I could have more contact with my lecturers. Studying on my own is not easy. And being far away is not helpful either. We need regular tutorials. People in Pretoria have everything … tutorials, the university and the lecturers and we have nothing. However, students who lived in the township and around the university still felt deprived from communicating with their lecturers on regular basis. Despite the proximity to the university one student said “we are so close and yet so far”. ODL advances learning as linear and individualistic which seems to isolate and marginalise students who reside in rural and urban areas. It is generally assumed that when students register in ODL contexts, they have an understanding of what it entails. However, most of the students come from a culture where learning usually take place in the classroom. As a result they are disappointed when they find themselves in an environment that does not offer face-to-face tuition (Lephalala and Makoe 2007). The study revealed 13 that students need support and structured learning experiences even if they are at a distance. Cultural characteristics To most students, learning is a collective social process whereby a student feels the need to interact with fellow students and teachers. Peers are the most influential group with whom they implicitly negotiated their understandings of the study materials. It is in these groups that “students are able to share their common beliefs about opportunity and education” (Bempechat and Abrahams, 1999, p. 856). In these cultures, meaning making is influenced by explicit negotiations with family members, teachers and peers. That’s why most students prefer to set up informal study groups where they share their fears and aspirations with other members of the group. Belonging to a group was helpful to most students because they studied together and in the process motivated each other. Zodwa: When you don’t have anyone to turn to … study group seem to be the only place where we all come together to motivate and encourage each other … I don’t think I would have made it this far without my study group. They have been my lifeline. It was clear in this study that students found the culture of autonomous and independent learning extremely problematic, partly because they felt that they were expected to be responsible for their learning with little support from the institution. Moore (1993) argues that where there is a high structure and low dialogue, the responsibility of learning is on the students. And this may lead to a feeling of isolation on the part of the learner. This shows that different social and cultural institutions with which students interact socially transmit the meaning and the value that students attach to the concept of learning. 14 Guiding Principles The support system that is being proposed has to see to it that students are participating in an active and challenging way in a learning process. In order to support distance learners effectively, course developers and teachers in distance education need to be aware of the variations of characteristics of the students and what they bring into the learning environment. They also need to understand who their learners are, where they are coming from, what type of support is needed and how best could they help in facilitating the learning process. This could be achieved through: Encouraging self-help study groups amongst students Offering support to students through tutoring Finding creative ways of using technology for educational purposes. Once we know who our learners are, it becomes easier to look at the support mechanisms that we can provide to our learners. The support mechanism has to see to it that students are participating in an active and challenging way in a learning process. The brief analysis of UNISA students’ characteristics indicates that students need support that is context specific. An effective support service system should motivate the learner, encourage group activities and provide feedback to learners. The function of learner support is to ensure the successful delivery of learning experience at a distance. 1. Motivational and Affective Factors One area of concern for most students in this study is lack of social interaction between themselves and their lecturers and other students. To address the problem of isolation, most students who participated in the study reported that they belonged to informal study groups even though this is neither encouraged nor discouraged by the university. Some goes as far as requesting an address list of other students in their area who are studying the same courses. In so doing, “students can feel immediate identification with others in their group and so lose feelings of isolation and over anxiety” (Thorpe 1995, p.84). It is in these study groups that students adopt a communal approach to learning by sharing responsibility for reading and explaining course material (Lentell and O’Rourke, 2004). In most African 15 cultures, group interaction is a strong factor determining values and social interaction. Although we agree that a student should be encouraged to be independent, he or she needs to be helped to reach that goal. In ODL, there is strong correlation between care and learner motivation. It is therefore important that distance education institutions need to look at other ways that can be used to facilitate social interaction. In developing student support systems, ODL institutions need to recognise some of the structures that are valued in African cultures and incorporate them in the support system programme. Students can only develop their potential if they are given assistance that is appropriate and addresses their needs. To help the informal study groups to become self-sustaining, distance education providers will do well by developing guides and programmes aimed at empowering students to help each other. Lentell and O’Rourke (2004) argue that ODL course and curriculum developers should include selfassessment exercises in their study material so that study groups can use them in their discussions. Supporting self-directed study groups will build communities of practice. Students become involved in a community of practice which embodies certain beliefs and behaviours to be acquired (Lave and Wenger, 1991). Learning, both outside and inside the formal educationsetting, advance through collaborative social interaction and social participation. . 2. Cognitive and metacognive Factors Most students cited lack of communication with their lecturers as the major problem. In the absence of communication with the people who are supposed to enhance their experience of learning, they felt lonely, alienated, insecure and alone. Thorpe (1998) believes that the quality of the interaction between a learner and his peers, a learner and his teacher, and a learner and his counsellor may enhance and even influence reactions to study. It must be kept in mind that distance learners have no one to discuss their problems with when they find it difficult to interpret tuition material. 16 In ODL, tutoring is at the centre of the learning process. While lecturers provide content through study material and learning resources, tutors help students to develop skills needed to comprehend, assimilate and apply the content, according to the 2003 Commonwealth of Learning tutor handbook. The role of the tutor therefore is to support, guide, enable and serve as a link between the students and the institution. There is no doubt that tutoring plays a critical role in supporting students. The UNISA’s 2007 ODL report suggests new ways of addressing limitations of the present student support systems. In the new system, each student should have a personal tutor who supports and understand a student as or she grows through the course. The tutor also has to provide feedback and mark students’ assignments. This role of a new tutor system is seen as “at the heart of learner support” (Tait 2003). Although this systems works well in Western educational institutions, Lentell and O’Rourke (2004) warns that what works other countries in the West may not necessary be appropriate in nonwestern societies. An efficient and effective support system should be grounded on the strength of the student context. It is in this regard that other tutorial systems that have been used effectively in other developing countries should be explored. It is about time, according to Lentell and O’Rourke (2004) that developing countries should start researching other models and methods of providing student support in situations of large student numbers. 3. Developmental and social factors One area that needs to be investigated in terms of providing support for students is the usage of technology (mobile technology) for educational purposes. Most people in Southern Africa, even those who live in rural areas, are more likely to own a cell-phone than a television or a computer. The University of Pretoria study found that the majority of their students who are enrolled in distance education programmes have access to cell phones. These students live in remote rural areas with little or no fixed line of telecommunication infrastructure and therefore they relied on using cell phones to communicate with their lecturers and each other (Keegan, 2005). 17 The potential for using cell phones for education purposes is enormous in a country of limited access to electricity and telephone networks; poor roads and postal services; and fewer people who have expertise of using computers. In recent years, the usage of cell phones has been embraced as a cost-effective way of providing support to teaching and learning in developing countries. UNISA students, who participated in a study conducted by Nonyongo and her colleagues in 2004, said that the SMS messaging is not only efficient, it is also convenient and reliable. Traxler and Dearden (2005) also found that students from Kenya, who participated in an in-service training programme showed interest in using (SMS) texting messages for learning purposes. He recommends that SMS texting can be used to support and encourage students, remind them about assignments, assessments or meeting as well as to deliver content such as hints, tips, revision etc. Although mobile learning is still not viewed as a viable tool of providing education in ODL, Keegan (2005) argues that the incorporation of mobile learning can afford new opportunities for teaching and supporting students in ODL. What emerged from Makoe (2006) study is that students also need informal academic support. The problem with academics is to assume that all what students are interested in is the content of the material. Synchronous communication via cell phones platforms such as “Mxit” an instant messaging application can be used to facilitate the process of real-time text chat between individuals and groups. The only way that distance education institutions can address the needs of their students, is to adopt strategies in which knowledge can be reorganized, implement curricula that students can identify with, understand the behaviour of students of other racial groups, and create an environment where students feel supported. It is important that distance education institutions need to look at other ways that can be used to facilitate support systems that are responsive, context-specific and integrated into the whole institutional culture. The aim of supporting learners is to empower them so that they can take control of their learning. 18 References Anderson, T., 2008. Towards a theory of online learning. In Anderson T. (ed.), The Theory of Practice of Online Learning, AUPress, Athabasca University. Brindley, J.E., and Paul, R., 2004. The role of learner support in institutional transformation - A case study in the making. In J. E. Brindley, C. Walti, & O. Zawacki-Richter (Eds.), Learner support in open, distance and online learning environments Oldenburg: Bibliotheks- und Informationssystem der Universität Oldenburg: 39-50. Beheler, B., 2009. Student Centered Learning Enviroments and Technology Applied to Special Education, Learning Theory and Educational Technology, EdTech, Boise State University https://sites.google.com/a/boisestate.edu/edtech504/behelerb, (Accessed July 2011). Bruner, J., 1996. The Culture of Education. Cambridge: Harvard University Dahl, B., 2003. A synthesis of different psychological learning theories? Piaget or Vygotsky, Philosophy of Mathematics Journal, 17, 24 pages. www.ex.ac.uk/~PErnest/pome17/pdf/bdahl.pdf (Accessed 5 March 2004) Glennie, J. and Bialobrzeska, M. 2006. Overview of Distance Education in South Africa, A South African Institute for Distance Education report http://www.saide.org.za/resources/ (Accessed 10 January 2007). Keegan, D. 2005. The incorporation of mobile learning into mainstream education and training, Proceedings of the 4th World Conference on Mlearning, Cape Town, 25-28 October, http://www.mlearn.org.za/CD/papers/keegan1.pdf, (Accessed January 25, 2008) 19 Knowlton, D.S., (2000) Theoretical framework for the online classroom: a defense and deliantion of student-centered pedagogy, New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 84, 5-14. Lave, J. and Wenger, E., 1991. Situated Learning, Legitimate Peripheral Participation, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press Lentell, H. and O’ Rourke, J., 2004. Tutoring large numbers: an unmet challenge, International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 5(1) www.irrodol.org/index.php/irrodol/article/viewArticle/171/253 (accessed 21 September 2008). Lephalala, M.M.K. and Makoe, M., 2007. Learners’ voices: using the sociocultural framework to understand South African distance learners, a paper presented at the International Conference on Learning, Johannesburg, 26-29 June 2007. Makoe, M. 2006. South African distance students’ accounts of learning in the socio-cultural context: a habitus analysis, Race Ethnicity and Education, 361380. May, S. (1994). Women’s experiences as distance learners: access and technology, Journal of Distance Education, 9(1), http://cade.athabascau.ca/vol9.1/may.html (Accessed 26 April 2006). McCombs, B.L. and Whistler, J.S.,1997. The learner-centred classroom and school: Strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. San Fransisco, Jossey-Bass. McCombs, B.L. and Vakiliu, D. , 2005. A learner-centred framework for elearning, Teachers College Record 107, 8, 1582-1600. Moore, M.G. 1993. Theory of transactional distance, in D. Keegan (ed), Theoretical Principles of Distance Education, Routledge, London, 22-38. 20 Pulist, S.K., 2001. Learner-centredness: An issue of institutional policy in the context of distance education, Turkish online Journal of Distance Education 2 (6) http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/tojde4/pulisttxt.html (Accessed 16 October 2008) Nonyongo, E., Mabusela, K., Monene, V., 2005. Effectiveness of SMS communication between university and students, http://www.mlearn.org.za/CD/papers/Nonyongo%.pdf (Accessed 2 February 2008) Rumble, G., 2000. Student support in distance education in the 21st century: Learning from service management, Distance Education, 21(2), 216-235 Sewart, D., 1993. Student support systems in distance education, Open Learning, 8(3), 3-12 Simpson, O., 2002. Supporting students in online, open and distance learning 2nd Edition. Kogan Page, London, UK. Tait, A., 2000. Planning student support for open and distance learning, Open Learning, 287-298. Tait, A. ,2003. “Reflections on Student Support in Open & Distance Learning”, International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 4(1), 2-8. Thorpe, M., 1995. Bringing learner experience into distance education in Sewart, D. ed. One world, many voices: Quality in open distance learning: Selected papers from the 17th World Conference of the International Council for Distance Education, International Council for Distance Education and the Open University. Milton Keynes: Open University, 364-367. Thorpe, M. 2001. Rethinking Learner Support: the challenge of collaborative online learning, A paper presented at SCROLLA Symposium on Informing Practice in Networked Learning, Glasgow, 14 November 2001, http://www.scrolla.ac.uk/papers/s1/thorpe_paper.html (Accessed, 6 July 2008) 21 Traxler, J. and Dearden, P (2005) The potential for using SMS to support learning in organisations in Sub-Saharan Africa, proceedings of the Development Studies Association Conference, Milton Keynes, September 2005, www.wlv.ac.uk/PDF/cidt-article20.pdf, (Accessed, 25 January 2008) University of South Africa (UNISA), 2010. Institutional Information Portal http://heda.unisa.ac.za/indicatordashboard/ (accessed 10 July 2010). Vygotsky, L.S. (1930/1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, M.A. Havard University Press 22