trust during international military missions

advertisement

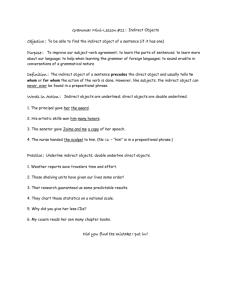

TRUST DURING INTERNATIONAL MILITARY MISSIONS Maria Fors Swedish National Defence College, Department of Leadership and Management 651 80 Karlstad, Sweden Maria.fors@fhs.se Karlstad University, Sweden Gerry Larsson Swedish National Defence College, Department of Leadership and Management University of Bergen, Norway Department of Psychosocial Science Paper presented at the 1st ISMS Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, November 25-26, 2009 Trust during international military missions In recent years the Swedish Armed Forces has changed from an invasion defence to being mission-based. This implies that Swedish military officers take part in rapid reaction forces in areas of crises and conflicts. Previous research shows that trust is an important factor of success in battle and central to sustaining team effectiveness but during time-limited international missions the time necessary for developing trust does not often exist (Bass, 1990; Boer, 2001; Gal & Mangelsdorff, 1991). Trust during these kinds of international missions is a relatively unexplored area of research. Several studies notice the important of trust, but few actually study the phenomenon in a military context (Gal, 1986; Maguen & Litz, 2006). There are many definitions of trust. The definition used in this study is that trust “is the undertaking of a risky course of action on the confident expectation that all persons involved in the action will act competently and dutifully” (Lewis & Weigert, 1985, p. 971). To gain a deeper understanding of trust during international missions, a qualitative study was conducted with the aim to study how critical incidents that had occurred during Swedish military operations in Afghanistan had influenced the trust of leaders, subordinates, and group members. The results of the study were operationalized to a quantitative questionnaire to follow up the results from the first study. Method The qualitative study The selection of participants follows the guidelines of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) and was guided by the desire to find informants with a wide variety of experiences. Twenty-one informants, military and civilian, who had served in Afghanistan in 2005 - 2008, participated in the study. The informants represented (a) indirect leaders (unit commanders), (b) direct leaders (team/troop leaders for the teams involved in incidents), (c) subordinates involved in incidents, (d) subordinates part of the team but not directly involved in incidents, and (e) individuals not part of the team involved but part of the unit. All participants were Swedish male, 25 – 50 years old. Sixteen were military officers (lieutenants to colonels), one was a soldier and four were civilians (for example nurses and operating staff). Ten had previous served in Afghanistan and/or other operations, while eleven had non prior experience from international military operations. 2 The participants belonged to three different units which had been exposed to different incidents during their service in Afghanistan. Two of the units were temporary made up for the specific mission while the third one was regular (Special Forces). The unit commanders were approached and they agreed to participate. They were asked to choose an incident which had affected them and the involved individuals to a great extent. The commanders were also asked to suggest subordinates that could be relevant for the study. A so-called snowball sampling was therefore used. The incidents reported in the study were mainly attacks by Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) where Swedish personnel was killed, injured or survived without injuries. The groups involved were sometimes also part of other incidents like being fired at or attacked by Rocket Propelled Grenades. The quantitative study Participants The sample was comprised of Swedish military personnel who had served in Afghanistan. About 2000 questionnaires were distributed to six units who had served in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2009. The exact sample size is difficult to calculate due to incomplete address list. The lists contained individuals who had not completed their training or who discontinued their service before the rotation to Afghanistan. It was also too time-consuming to compare the lists for individuals that occurred in several list because of service in two or more of the current units. This means that individual who participated in several missions have received as many questionnaires as missions. Number of responses received is 622. 3 Table 1. Description of the participants Participants (n=622) Background characteristics Sex Men Women Age > 30 31 – 40 41 < Bransch of service Army Navy Air force Military background Career or reserve officer Civilian n % 560 57 89.9 9.1 266 204 125 43 33 20 475 51 72 76 8.2 11.6 244 368 39.2 59.2 Instruments Trust in group members, the direct leader, the deputy direct leader, and the indirect leader was measured. The direct leader is defined as the individual’s closest manager, the deputy direct leader as the closest manager’s deputy, and the indirect leader as the unit commander/ commanding officer. Cronbach Alpha on the trust scales ranged from .75 to .92. The items contained questions about trust in the leaders/group members’ personal attributes, task competence, and competence in battle. The respondents answered the items using a 6-point rating scale anchored by 1 (very low) and 6 (very high). Statistics The analysis was carried out using non-parametric statistics (the Kruskal-Wallis test, MannWhitney U-test, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test). Statistical significance was assumed at p < 0.05, except for those cases were a Bonferroni correction was applied. 4 Results The qualitative study Individual factors The trustee •General trust in •Individual others characteristics •Expectations •Task competence •Competence in based on experience •Motivation battle Context before Context during •Training/time •Expected risk •Recruitment •Stress •Difficulties to adjust •Boredom •Threats Critical incident The level of trust affects actions Figure 1. Factors influencing trust during international missions Trust during international operations appears to be developed and influenced by individual factors, perceptions of the trustee, the context before the operation, and the context during operations. The different factors are described below. Individual factors Individual factors of importance in the one who is to trust someone is her or his general trust in others. There seems to be two initial standpoints: the glass is full versus the glass is empty. The first indicates that a person enters a relationship trusting another individual until that person does something to jeopardize the trust, while the latter represents an attitude of others having to prove by action that they can be trusted. Also prior experiences are important. Knowledge of people, common background (combat arm, home district, training unit, etc.) and reputation contributes to trust based one what experiences an individual has. Individuals sometimes have an idea of how others should be which is based on prior experiences. How a leader should be, a nurse etcetera. If this idea corresponds 5 with others, then trust is developed. Distrust can also be overcome if the individual’s motivation for the task and the operation is high. In those cases it is not as important to have high trust in leaders, subordinates or group members as if the motivation is low. You can make allowance for some distrust. Sometimes a positive expectation trust is developed which means that you don’t fully trust an individual but you have confidence that it will be better with time. The Trustee The trustee, that is the person who is to be trusted, seems to be judged by others on three factors: (a) individual characteristics such as if the person is perceived as humble, calm, or responsible, (b) task competence, if the person is able to manage his/her position, and (c) competence in battle, if the person is perceived to be able to handle a dangerous and risky situation. The context before the mission The context before the operation, during the training, also affects trust development. If the group train together most of the time, there is a better chance of developing trust to each other. But mostly the time is not enough. During different exercises, expectations about others behaviour are confirmed or rejected. The informants report that there is often not enough time to get to know each other and develop trust during training before the service. One contributing cause is different lines of training which means that the individuals in one group is trained separated from the group, together with other individuals in their professional field of expertise. It also seems as the perception of the expected risk during the operation affects trust development. If the risk of getting into a risky situation seems to be less likely, it is more important to trust a persons individual characteristics, to get on well. If the risk is perceived as high, more importance is put on task competence and competence in battle. If a leader has had the opportunity to recruit his subordinates, then trust seems to develop faster. The same can be applied to if the individuals know that the recruitment procedure has been careful and tough, as in the case of Special Forces. The context during the mission When in Afghanistan, trust development seems to be influenced by stress. Individuals can change their behavior because of the stress that comes from being on an operation in an unknown environment. When others don’t recognize the behavior they initially based their trust on, the trust gets thinner. Some positions have periods when the workload is less which can lead to 6 feelings of boredom. This appears to contribute to conflicts which, if trust has not fully developed, can prevent trust from thickening. If the group is exposed to threats trust seems to increase. Some individuals also have problems adjusting to the new environment which also can lead to trust problems. Critical incidents and trust When a critical incident occurs, the level of trust that the individuals at this point have developed to leaders, subordinates and group members can affect actions during the incident. For example, trust appears to affect risk perception in both positive and negative ways. Positive when you dare to act but negative if you act incautious. When trust exists in the group, everyone can do their work and take initiatives being confident that team members can handle the situation. Lack of trust on the other hand can imply not letting someone act without controlling and during the incident every personal resource can be indispensable. The quantitative study Trust development Table 2. Estimation of trust in group members and leaders, before and after deployment. Before After M M Group members 4.92 4.99 Direct leader 4.56 4.50 NS Deputy leader 4.57 4.60 NS Indirect leader 3.83 3.59 z p 3,290 5.210 .001 .000 Table 2 shows that trust in group members is rated higher after the mission than before while trust in the indirect leader decreases after the mission. Trust in group members is also estimated higher than trust in both direct and indirect leaders (p<.001). Trust in the indirect leader is also measured significantly lower than trust in direct and deputy leaders (p<.001). These results are also supported by data from the qualitative study. That trust in the indirect leader is estimated as lower than trust in other leaders and group members can be do to the fact 7 that subordinates experience themselves not being affected by the indirect leader in the same extent and not having any personal contact or relation with him. Some illustrating quotes: “We did not see him so often and if we did it was nothing to waste time on. What I can not influence, I do not waste time on”. “He is a colonel and I am a group leader at a quite low level, it is not that we meet daily. We see each other occasionally but there is very little that we still have to do with each other” “In a way you have no clue what they do. As I said, we didn’t see him that much.” That trust in group members is higher and increases can be explained by the quote below: “On the one hand, we had to trust each other. There was nobody else who could come and help us if it went to hell. And then the more we began to know each other so it was also more of these soft parts. Not only in terms of that we had to but the personal relation grew.” As the quotes illustrate, trust seems to be influenced by the frequency of personal contact which is facilitated in the group compared to in the relationship to the leaders. One explanation for that trust in the indirect leader decreases during the mission can be that the leader almost always has to take decisions that are not supported by the subordinates. Especially mentioned are safety decisions were the indirect leader and his closest managers decide that the area can not be patrolled a few days immediately after some kind of incident. The subordinates feel that they are prevented from doing their work. We illustrate: “We felt that the management was faint-hearted, to not put their foot down.” “He /the CO/ said that he has responsibility for us and I said to him /about the safetydecision/: I don’t buy it, we are all of age. We have come here by free will, it is voluntarily. If you say patrols should be carried out, no one will blame you.” Discussion The results show that trust during international military operations is influenced by individual factors, perceptions of the trustee, and contextual factors. These findings emphasizes the findings of Hardin (1992) that claimed that trust is a three-part relation (properties of a truster, attributes 8 of a trustee, and contextual). It should also be noted that trust in this study spans over different contexts, the one before the mission during training, and the one during the mission, in the mission area. Results from both the presented studies show that trust in group members is estimated higher than in direct and indirect leaders. Trust in direct leaders is also rated higher compared to trust in the indirect leader. Trust in group members also increases during the mission while trust in the indirect leader decreases. This could be do to the fact that group members spend more time with each other and with the direct leaders compared to the indirect leader were there often is a lack of personal contact. This implies that personal contact is important for trust development. Since several informants describe that there is not enough time to get to know each other during training, individual’s take on an important and potentially dangerous task without feeling real trust to the people you will work with. The mean scores show an estimated high trust in group members as well as direct leaders before the mission. This can, however, be a reconstruction after the mission. Since the indirect leader is not involved in all subordinates tasks and situations on a detail level, perhaps a high trust in the indirect leader is not of utmost importance. It is possibly more important to have high trust in the ones closest to you, the ones whose direct actions affect you immediately. If knowledge of people and personal relations are important for developing trust, than activities that urge on the trust development, for instance team-building, is probably important to set aside time for. 9 References Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass & Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research and managerial applications. Third Edition. New York: The Free Press. Boer, P.C. (2001). Small unit cohesion: The face of Fighter Squadron 3-V1. G. IV. Armed Forces and Society, 28, 33-54. Gal, R. (1986). Unit Morale: From a Theoretical Puzzle to an Empirical Illustration – An Israeli Example. Journal of applied social psychology, 16, 549-564. Gal, R., & Mangelsdorff, A. D. (Eds.) (1991). Handbook of military psychology. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. Hardin, R. (1992). The Street-level Epistemology of Trust. Analyse and kritik, 14, 152-176. Lewis, D., & Weigert, A. (1985). Trust as a Social Reality. Social forces, 63, 967-985. Maugen, S., & Litz, B. T. (2006). Predictors of Morale in U.S. Peacekeepers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 820-826. . 10