P = $1 - My LIUC

advertisement

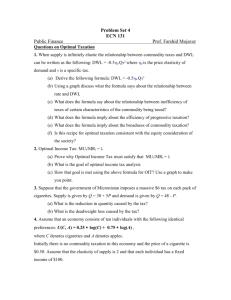

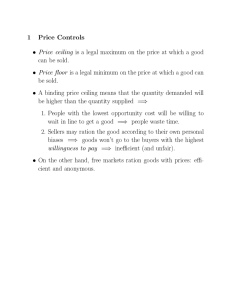

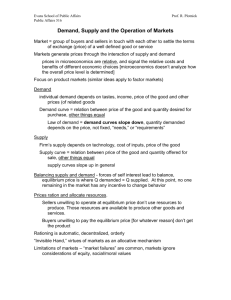

Lecture 4 Materials Market Efficiency and Welfare, Taxation Textbook: Chapters 6 (pp. 124 – 133), 7, 8. LECTURE NOTES 1. Tax Incidence and Elasticity The incidence of a tax depends not on whom the tax is levied but on the relative elasticities of the buyers and sellers in the market. A tax falls most heavily on the market participants with the relatively lower elasticity. Let Ed be the elasticity of demand of buyers and Es be the elasticity of supply of sellers. The pass-though formula allows us to estimate the percentage of the tax borne by buyers: Pass-through formula: Es/(Es – Ed) For example: let Ed = -0.5 and Es = +2.0. Then: Es/(Es-Ed) = 2/(2- (-0.5) = 2/2.5 = .80 Thus, with these elasticities, buyers bear 80% of the tax burden and sellers bear 20%. 2. Taxation and Economic Welfare We studied how a tax on a good affects its market price and the quantity sold as well as how the relative forces of demand and supply determine how the burden of the tax is divided between buyers and sellers. What about the effect of the tax on overall welfare? (Remember what we mean in economics by welfare.) Well, first of all, it is obvious that both buyers and sellers of the good being taxed are worse off as a result of the tax: the price buyers pay is higher and the price sellers receive is lower than without the tax. Who is better off?: the recipients of the tax revenue raised by the tax. The question is then: is the extent to which the buyers and sellers are worse off greater or less than the extent to which the recipients of the tax are better off? The (not so surprising) answer is that viewed strictly in this way there is always a deadweight loss associated with any tax. The greater the elasticities of supply and demand, the greater the deadweight loss associated with the tax. Why? Because the more elastic these are, the more quantity demanded and supplied changes as a result of the tax (i.e. is distorted from the levels that would have been demanded and supplied absent the tax) and, thus, the greater the amount of marginal buyers and sellers who cannot transact as a result of the tax (although they would have been willing to in the absence of the tax.) For example, a tax on labor is expected to have a greater deadweight loss associated with it depending on whether we believe that the supply of labor is more or less elastic. There is empirical evidence that the supply of labor is fairly inelastic, in part because most people would be willing to work fulltime regardless of wages. If this is the case, then the welfare loss associated with taxation is not very great. But if the supply of labor is believed to be more elastic, then the DWL is greater. Behavioral effects of higher elasticity of labor supply: more overtime work supplied at higher wages; married women with children more willing to work at higher wages; people would retire later; reduction in underground economy, illegal activities at higher wages. Thus, if labor supply is more elastic then it will respond to a tax on labor by working fewer hours (e.g. overtime), fewer second workers enter the work force, workers retire earlier, higher amount of illegal/underground economy. The size of the tax matters: The size of the DWL as well as the amount of tax revenue associated with a tax depends on the size of the tax. If the tax is very small (compared to the price of the good) the DWL is small as is the tax revenue. As the tax gets larger, both the DWL and the tax revenue increase. But, for very large taxes, the DWL gets very large while the tax revenue is relatively small. Why? Because the large size of the tax has shrunk the market for the good dramatically so much less is sold. The Laffer Curve: (Arthur Laffer, 1974) Laffer argued that as tax rates rise, the DWL associated with them also rises but the tax revenues eventually start to decline because people chose to work less (their supply of labor is in fact more elastic at higher tax rates.) So, very high tax rates are ineffective. In fact, this implies that if labor finds itself in the downward portion of the Laffer curve, a cut in the tax rates would result in an increase in tax revenues. This rationale was what in part motivated President Regan’s tax cuts in 1980. (In fact, when Regan was an actor during WWII, the marginal tax rate was extremely high –90 %. After 4 movies in a given year, actors found themselves in the top income tax bracket and found that it was not worthwhile to make another film.) Empirical studies have concluded that the Laffer curve effect does not hold, except perhaps at extremely high marginal tax rates, such as those in some of the Scandinavian countries, such as Sweden and Norway. So, if taxes result in DWL, why do we have/want them? The market (interaction of buyers and sellers trying to maximize their respective utilities and profits) outcome: may ignore important negative externalities, may not adequately provide some essential services that are important for society (because the positive externalities associated with them are not recognized by the market or because of common resources/public goods complications) may result in equity concerns. So, we appropriate tax proceeds and use them to correct these imperfections, to fund programs or redistribute income, etc. Furthermore, we may believe that the tax revenue if used properly can improve society by more than the initial size of the revenue itself (multiplier effect). Recall also that when the tax is a Pigovian tax aimed at reducing an externality (e.g. an emissions fee in the case of pollution), then the tax itself enhances economic efficiency. Lecture Reading: Beet a Retreat, The Economist.com, June 23, 2005 http://www.economist.com/node/4112150 SAMPLE PROBLEMS The Impact of a Gasoline Tax The idea of a large tax on gasoline, both to raise government revenue and to reduce oil consumption and US dependence on oil imports has been discussed for many years and is of particular relevance in the current world environment. In this problem, we consider how a 50 cents/gallon tax would affect the price and consumption of gasoline as well as the amount of revenue it would raise. Consider the conditions in the oil market in the mid 1990s, when gasoline was selling at approximately $1/gallon and total consumption was approximately 100 billion gallons/year. At the time, the demand and supply of gasoline were estimated as: Qd = 150 – 50P Qs = 60 + 40P Where P = price per gallon and Q = billions of gallons. a. Calculate the market equilibrium without the tax. b. Calculate the market equilibrium after the imposition of the tax. In particular, what happened to gasoline consumption as a result of the tax? c. What is the incidence of the tax, i.e. the proportion of the tax borne by gasoline buyers versus sellers? d. Compute the total amount of tax revenues raised by the tax. e. Compute the dead weight loss from the tax. Draw a graph showing the market outcome before and after the tax, total tax revenues and DWL associated with the tax. f. Are the tax revenues from the tax large or small in comparison to the dead weight loss associated with the tax? g. What do you conclude about this kind of tax in the short run? From the point of view of society, is it a good idea? In answering this question, are there non-“economic” factors that have to be taken into consideration? h. Class Discussion: The questions above are based on the immediate (short-run) effects of the tax. How would your answers to (b- f) differ if you took a longer run perspective? Answer: a. Without a tax, the market equilibrium price and quantity are as follows: Qd = Qs 150 – 50P = 60 + 40P 90 = 90P P = $1 And Q = 150 – 50(1) = 100 billion gallons b. As a result of the tax, there is a wedge between what buyers pay and what sellers receive, i.e.: Pb – Ps = 0.50 or Pb = Ps + 0.50 The demand equation becomes Qd = 150 – 50 Pb The supply equation becomes Qs = 60 + 40Ps The new market equilibrium will occur where Qd = Qs Combining these 4 equations yields: 150 – 50 Pb = 60 + 40Ps 150 - 50 (Ps + 0.50) = 60 + 40Ps 150 – 50Ps - 25 = 60 + 40Ps 65 = 90Ps Ps = .72 and Pb = Ps + 0.50 = 1.22 The new equilibrium quantity Q* is determined by substituting the new price paid by buyers Pb of $1.22 in the Qd equation or the new price received by sellers Ps in the Qs equation: Qd = 150 – 50(1.22) Q* = 89 billion gallons/year Thus, the tax results in an 11% decline in the quantity of gasoline consumption (from 100 to 89 billion gallons/year.) c. The incidence of the tax is shared approximately equally between buyers and sellers. Because of the tax, buyers pay 22 cents more (1.22 – 1.00) than they did before and sellers receive 28 cents less than they did before (1.00 - .72). d. Total revenue to the government from the tax = 89 billion gallons * 0.50 tax per gallon = $44.5 billion e. Deadweight loss from the tax = reduction in consumer surplus + reduction in producer surplus. Reduction in CS (area C) = (11 billion gallons * $0.22)/2 = $1.21 billion Reduction in PS (area D) = (11 billion gallons * $0.28)/2 = $1.54 billion DWL = $2.75 billion Referring to the graph below, total tax revenues correspond to areas A + B and total DWL corresponds to areas C + D. f. The DWL is about 6% (2.75billion/44.5billion) of the total tax revenues raised by the tax so the tax revenues are large relative to the DWL. S1 $/Gallon Pb = 1.22 A C Pm = 1.0 B D Ps = 0.72 D 89 100 Gallons (billions per yr.) g. From a strictly economic point of view, the tax results in an overall DWL, so society is worse off. However, the strict economic analysis assumes that every dollar of DWL is a dollar reduction in well-being for society and every dollar in tax revenues is a dollar increase in well-being for society. However, from the point of view of society, the DWL must be balanced against any additional benefits that the tax revenues may bring. For example: the tax revenues may be used to develop new forms of energy efficiency which reduce the cost of energy production and reduce dependency on foreign oil and these result in benefits that are far greater than the dollars invested in these programs. Note also that the tax raises a lot of revenue compared to the relatively small DWL associated with it. Similarly, the loss in consumer surplus resulting from the tax is a valid measure of reduction in well-being for society only if we accept that well-being can be measured by the area under the demand curve (i.e. consumers’ willingness to pay) and above price. h. In the long run, we would expect the elasticity of demand for gasoline to increase (demand curve is flatter—as in graph below) as consumers find ways to conserve, purchase more fuel efficient cars, etc. This increase in the elasticity of demand would result in the following changes compared to the short-run results: (1) a smaller increase in the market price of gasoline paid by buyers (Pb < $1.22) and a greater reduction in the consumption of gasoline to (Qm < 89 billion gallons/year), (2) reduction in tax revenues to the government associated with the tax because although the difference between Pb and Ps is still 50 cents, the market quantity of gasoline sold Qm is lower (the height of the tax revenue rectangle is the same but the base is smaller). (3) increase in the size of the deadweight loss (DWL) associated with the tax so that the DWL will be larger as a percentage of tax revenues. The area of the DWL triangle is larger because although the height DL is the same, the base LW (100 – Qm) is greater. (4) smaller incidence of the tax on buyers (Pb-P) and larger incidence on sellers (Ps-P) because, as a result of the increased elasticity of demand for gasoline in the longer run, supply is now relatively less elastic compared to demand. S1 $/Gallon Pb W Pm = 1.0 D PS L Qm 100 Gallons (billions per yr.) (5) As a result of the tax, the overall demand for gasoline may also decrease over time, causing an inward shift in the demand curve.