Understanding Fabric

advertisement

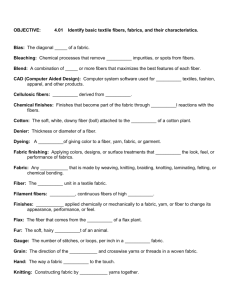

Pre-Costuming Understanding Fabric Maîtresse Irène leNoir irene@chezirene.com © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Permission to print a copy for your own use freely given. Please contact me for permission to reprint or distribute. In order to properly understand fabric, you need to understand how it’s created. That means understanding where the fibers that make up the fabric come from, how they’re turned into fabric, how the fabric may be colored, and how the fabric may be treated or decorated. Fiber Content The basic building blocks for all fabrics are fibers. Although the number of different fibers is quite large, they can all be categorized as either natural or manufactured. The natural fibers can then be further divided into plant or animal fibers, and the manufactured into synthetic and cellulosic. (The term synthetic is also commonly mis-used to refer to all manufactured fibers.) Synthetic fibers are composed of chemical compounds derived from petroleum or natural gas. Cellulosic fibers are derived from cellulose, a natural fiber. Because of this natural source for the raw material, many people mistakenly believe that cellulosic fibers are natural fibers. However, chemical processes are used during the manufacture of cellulosic fibers that dissolve, refine, and reconstitute the cellulose. In the process, the cellulose is often weakened or even partially replaced with synthetic compounds. Some common fibers and their derivations follow. Fiber Acetate Acrylic Angora Cotton Hemp Linen Lyocell Nylon Olefin Polyester Ramie Rayon Silk Spandex Vinyl Wool Category Cellulosic Synthetic Animal Plant Plant Plant Cellulosic Synthetic Synthetic Synthetic Plant Cellulosic Animal Synthetic Synthetic Animal Derivation Cellulose modified with acids Long-chain synthetic polymers composed of acrylonitrile units Hair of the angora goat or angora rabbit Seed hairs of the cotton plant Stem of the hemp plant Stem of the flax plant Cellulose modified without synthetic replacement Long-chain polymeric amides Polymers composed of ethylene, propylene, or other olefin units Resin formed of polyhydric alcohols and dibasic acids Stem of the ramie plant Cellulose modified with some synthetic replacement Silkworm cocoons Polymers of polyurethane Polymerized vinyl compounds Hair of sheep or other animals Aside from the classification as to their source, fibers can also be classified as either filament fibers or staple fibers. Filament fibers are those that are extruded to an indefinite length. While most filament fibers are manufactured, silk is an example of one that's naturally occurring. Staple fibers, by contrast, have set lengths. Staple fibers can occur naturally, or they can be produced by cutting a filament fiber into shorter lengths. Sometimes the comparative terms of long or short are used to describe the staple length of a given fiber in comparison to others of the same type. As an example, Egyptian cotton comes from a variety of cotton that has a longer staple length than most cottons. © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 1 Different fibers have different properties. Natural fibers breathe, and are therefore usually cool in warm weather and warm in cold weather. In contrast, synthetics don’t breathe well. So they aren’t very comfortable in warm weather. Cellulosic fibers breathe better than synthetics, but usually not as well as natural fibers. Cotton is absorbent. Linen is extremely durable. Polyester is resistant to wrinkles. Silk has a high tensile strength and resists abrasion. Spandex is highly elastic. Vinyl is waterproof. Wool retains warmth even when wet, and tends to cease burning when removed from a source of flame. But these are just a few examples that only skim the surface. A complete listing of the properties of these and other fibers could fill a book. Different fibers have different innate care requirements. Unfortunately there's no way to definitively state which methods can be used for which fabrics, as too many variables can affect the type of care the fabric will require. However, a few generalizations can be made. One is that all natural fibers can be washed. They may need to be washed in cold water or by hand, but they can be washed. Another is that very few fabrics truly need to be dry-cleaned. They can often be hand-washed or machine-washed on a delicate cycle instead. If you’re ever in doubt about how to care for a fabric, wash (or otherwise clean) a test swatch first to see how it behaves. Yarns Although not always necessary, most methods of fabric construction require the fiber to first be formed into a yarn. But note that when speaking about fabric construction, a yarn doesn’t need to be as thick as we usually think of when we think of yarn. A “yarn” can actually be as thin as what we would normally consider thread. To form a staple yarn, staple fibers are first carded (combed) to align the fibers. At this point noils (shorter or tangled staple fibers) are sometimes also removed. Once carded, the fibers are spun (twisted) together to form a yarn. Filament yarns are formed from filament fibers gathered together and laid parallel along their lengths. These fibers can then be spun, but don’t need to be. Some yarns are monofilament, or formed from a single filament fiber. Yarns can also be formed from filament fibers spun together with staple fibers. Two or more spun lengths can also be plied (twisted together) to add strength, bulk, or for appearance. A yarn formed in this manner is referred to as a two-ply yarn, three-ply yarn, etc. Although not yarns in the strict sense of the word, sometimes you’ll encounter fabrics created from what could be referred to as unspun yarns. In these cases, carded staple fibers aren’t spun together, but are instead just aligned into a long, thin yarn shape. But without the twist to hold the fibers together, these unspun yarns are very weak and pull apart easily. Sometimes yarns are spun with slubs (irregular thickened spots) along their length. These slubs can be an accidental defect. But they’re often deliberately included to give the yarn texture. As an example, noils that were removed in the carding process can be spun either by themselves or added to longer staple fibers to produce noil yarn. Other decorative yarns can be created by combining plies of different fibers or colors. In addition, plies spun with different tensions can be combined to create textured yarns. © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 2 Woven Fabrics Probably the most common type, woven fabrics are created from the intersection of two sets of yarns. The yarns running the length of the fabric, the warp, are placed parallel to each other along the length of a loom. Then the weft yarn is passed over and under the warp, perpendicular to the warp, forming the fabric as it moves back and forth. Woven fabric has a grain. That is to say, the yarns are aligned in a certain direction and pieces of fabric cut at different angles across the grain will behave differently. The lengthwise grain of the fabric, sometimes simply referred to as the grain, runs in the direction of the warp yarns. The crosswise grain runs in the direction of the weft yarns. Any angle not in line with the lengthwise or crosswise grains is referred to as bias. The true bias of a fabric is the forty-five degree angle between the lengthwise and crosswise grains. Unless a fabric is woven with an elastic fiber, it won’t stretch along its lengthwise or crosswise grain. But it will stretch along the bias. Another characteristic of woven fabrics is they have a tendency to fray (come unwoven) along cut edges. While it’s usually necessary to take steps to prevent woven fabrics from fraying, some fabrics are less prone to fraying in general, and most fabrics are less prone to fraying when cut on the bias. There are many different patterns in which fabric can be woven, and many of these have names. An evenweave, also called a plain weave or a tabby weave, is the most basic weave. In this weave, the weft yarns pass over one warp yarn and under the next. A basketweave is similar to an evenweave, but with groups of two or more yarns being treated as one. A rib weave is characterized by prominent ribs in the weft. These can be created by using larger yarns in the weft than are used in the warp, by using two or more yarns in the place of one weft yarn, or by using many more yarns in the warp than in the weft. A twill weave is characterized by diagonal lines across the surface of the fabric. A warp-faced twill (or simply twill) is formed when each warp yarn floats (passes) over two or three weft yarns before passing back under, with the spacing of the floats arranged to produce the diagonal lines. A weft-faced twill is one in which the weft yarns float across the warp. An even-faced twill is one in which the warp (or weft) yarns pass over and under an equal number of yarns. While there are many patterns and designs that can be created using variations of twill weave, some are distinct enough they have specific names. Herringbone twill is a variant in which the floats are arranged so as to produce zig-zag lines. Diamond twill is one in which the floats are arranged to form repeating diamond motifs. Houndstooth is a variant in which the floats and stripes of color in the warp and weft are arranged to form an allover design of barbed or broken squares. Twills can also be described numerically. As examples, a 3:1 twill is one in which the yarns float across three yarns before passing under one, while a 2:2 twill is one in which the yarns float across two yarns before passing under two. A satin weave is similar to a twill, in that yarns float across the surface. However, a satin is one in which the floats pass over 4 or more yarns. Additionally, the floats are arranged so as not to create any obvious diagonal lines, but instead just a smooth surface. A sateen is a weft-faced satin. Seersucker is a fabric woven with warp yarns of different tensions. These different tensions cause lengthwise puckered stripes to develop once the fabric is released from the loom. Piqué is © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 3 a fabric which can be somewhat similar in appearance to seersucker, with lengthwise and/or crosswise puckered ribs or figures. These puckered effects are created by interlacing dual warps. Pile fabrics have a raised surface of loops or sheared loops. Velvet is created by weaving a fabric with supplementary warp yarns which are drawn out and looped, and then sheared off, leaving a pile on the surface of the fabric. Alternately, it can be created by weaving two lengths of fabric with the supplemental warp passing between them, and then cutting the two fabrics apart. Velveteen is a fabric similar to velvet, but created with a supplementary weft. Corduroy is a style of pile fabric in which the pile has been cut or woven in stripes, called cords or wales, running the length of the fabric. Terrycloth has a pile of loops. A jacquard is a fabric woven on a jacquard loom. This type of loom differs from standard looms in that rather than controlling the warp yarns in groups, each warp yarn is individually controlled, allowing a much greater capacity for complex designs. A brocade is a fabric characterized by highly complex, often multi-colored designs created by using supplemental weft yarns, which intermittently float across the back of the fabric. A damask is a fabric formed from satin and sateen weaves, used to create reversible figured designs. A tapestry is a completely weft-faced fabric, often characterized by weft yarns that don’t pass the full width of the fabric, but instead fill smaller areas. Another style of figured weave is a dobby weave, produced on a loom with a dobby attachment. This attachment resembles a jacquard loom, and is used for weaving small motifs over a small number of yarns. Swivel weaves are made on looms with attachments for guiding additional weft yarns over limited areas. Leno weave fabrics are a variety of weave in which pairs of warp yarns cross over each other, locking the weft yarn in place. Double weaves are woven from two distinct warp and weft sets connected at intervals by the warp and/or weft of one passing through the other. Fabrics can also be woven with many other varieties of designs that have no specific names. Knit Fabrics The second most common type, knit fabrics are created by looping a yarn through itself. These loops, called stitches, are arranged in courses (rows across the width of the fabric) and wales (columns along the length of the fabric.) Traditionally, this was accomplished by hand with knitting needles, forming one stitch at a time. For modern mass production though, complex knitting machines are used that form an entire course of stitches in one pass. Although these methods for producing knits differ, they create fabrics that are structurally identical. Knit fabrics also have grain and bias. The stitches forming the fabric are oriented in a certain direction, and the fabric will behave differently at different angles across its grain. Unlike wovens, knits will stretch in any direction, though usually more so across the width of the fabric than along the length. Still, this property can be controlled through deliberate choices of yarn and tension. As a result, knits can be created that are stable (relatively stretch-free) or that stretch equally in any direction. Knit fabrics won’t fray the way wovens will, but they can unravel or run. Cut edges unravel as the stitches making up the knit fabric unloop themselves © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 4 along the length of the cut. Runs occur as wales of stitches unloop themselves in a chainreaction originating at a single broken yarn in the knit, and traveling up and down the length of the fabric from this initial break. As with wovens, there are many different patterns in which fabric can be knit. A plain knit, or stockinette, is the simplest, and has the appearance of interlocking V-shapes on the front and interlocking crescent shapes on the back. If the direction of the stitches is reversed the V-shapes occur on the back and the crescent shapes on the front, forming a purl knit. Rib knits are created by alternating wales, or sets of wales, of knit and purl stitches. Velour is similar to velvet or velveteen, but with a knit fabric for the base. Fake fur is usually manufactured as a pile fabric with a knit base. There are also a wide variety of decorative patterns that can be created by alternating knit and purl stitches in certain sequences and/or repositioning stitches within a course. Perhaps the most common of these patterned knits are cable-knits, in which stitches are repositioned to create the effect of twisting ropes or cables. A double knit, similar to a double weave, is knitted with two sets of needles, producing a double thickness of fabric, with the layers joined by interlocking stitches. Other Fabrics Felt is a type of fabric composed of irregularly oriented fibers which have been interlocked and formed into a sheet. This interlocking of the fibers is achieved through a combination of heat, moisture, and agitation. Not all fibers can be felted. In order for felting to be possible, the fibers need to have microscopic barbs along their length. During the felting process, these barbs grab hold of each other and interlock. Wool and certain synthetic fibers have these necessary barbs. Unlike wovens and knits, felt doesn’t have grain, as the fibers making up felt aren’t oriented in any specific direction. Because of this, felt won’t fray when cut and it also tends to be waterresistant. Felt will usually stretch, but only to a point. After that point, continuing to attempt to stretch the felt will simply begin to pull the fibers apart. Felt can also be shaped by using a combination of heat and moisture. There are still many other methods of fabric construction, some moderately common and some very obscure. Crochet is a technique similar to knitting in that it loops a continuous length of yarn through itself. However, crochet is performed with a single hook. Additionally, unlike knitting, crochet can't be mechanized. Netting is a process in which a length of yarn is looped and knotted to itself in an open pattern. Naalbinding is an obscure historic technique in which a continuous length of yarn is stitched to itself in interlocking loops. Sprang, another historic technique, involves crossing and twisting parallel yarns to produce a fabric that looks like a cross between knitting and netting. Macramé fabrics are formed by knotting yarns together in complex patterns. Lace is produced through a wide variety of techniques. Barkcloth is produced by hammering the bark of certain species of trees into a thin sheet. A variety of non-woven fabrics are created through varied techniques ranging from extrusion to felt-like processes. Leather, suede, and fur, while not really fabrics, can in all other respects still be treated as such. © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 5 Other Terminology Selvedges are the two long finished edges of the fabric, formed as the fabric is woven, knit, or otherwise created. Threadcount is a measure of how many threads per inch are found in a woven fabric. Gauge is a measure of how many stitches per inch are found in a knit fabric. It’s worth noting that for threadcount figures to give a truly accurate description, they must be given for both warp and weft, as they need not be the same. Similarly, gauge should specify stitches vertically and horizontally. It’s also worth noting that fabrics with a low threadcount or which have been loosely woven tend to shrink more than higher threadcount or more tightly woven fabrics of the same fiber content. This effect also occurs with lower gauge or looser knits. Drape is a word used to qualitatively describe how a fabric behaves when allowed to fall against itself or in folds. As an example, twills drape better than evenweaves. Body is a similar word used to describe how firm a fabric is. As an example, velveteen has more body than velour. Nap is a word used to describe any soft, fuzzy surface such as those found on flannel or pile fabrics. It’s also often used to indicate a fabric which has a directional nap, such as velvet, or the direction of the nap. Blends Not all fabrics are composed of just one fiber. Often, different fibers are blended together for any of a variety of reasons. Factors that can influence the reasons for creating the blend may include cost, durability, availability, and how readily the fabric accepts dye. There are several ways in which different fibers can be combined. The most basic is for the fibers to be mixed before the yarn is spun. Yarns can also be composed of plies of different fiber contents. Another variation is to spin the yarn with a core of one fiber and an outer wrapping of another. The fibers can also be combined by using yarns of different content when creating the fabric, such as using a warp of one fiber and a weft of another. Combinations of these methods can also be used. Coloring The simplest form of coloring fabric is to dye it a solid color. But there are many different ways of doing so. The most basic process is to dye the raw material, known as stock dyeing. One of the advantages of dying raw fiber stock is that different colors or shades can then be spun together to create complex yarns. For synthetics, pigment can be added to the chemical solution before the fiber is created. This process is known as solution dying, and has the advantage of being extremely colorfast. The next point in the fabric manufacturing process at which color could be added would be after the fibers have been spun into yarn. This is known as yarn dyeing. Yarn dyeing allows fabric to be created from yarns of different color, allowing the possibilities of plaids, brocades, and other woven-in designs. Space dyeing, a variation of yarn dyeing, is a technique in which yarns are dyed at intervals along their length. © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 6 Once the fabric has been created it can be dyed as whole cloth, which is known as piece dyeing. The process of submersing cloth in a dye solution is referred to as vat dying. But not all solid color fabrics are dyed in this fashion. Sometimes surface dying is used instead. In this process the fabric is essentially painted on both sides with the dye. Surface dying is commonly used because of its cost-effectiveness, and usually there's no discernable difference from vat dyed fabrics. But sometimes during the surface dyeing process the fabric wrinkles or something gets caught between the fabric and the source of the dye. As a result, the dye isn’t evenly applied over the entire surface, leaving undyed areas. Because of this potential, you should be careful when dealing with surface dyed fabrics, and watch for any flaws as your fabric is being measured out. Over dyeing, also known as top dyeing, is a simple variation of vat dyeing in which the fabric is dyed in one dyebath, and then again (or multiple times) in the same or another dyebath. Over dyeing can be used to build up deeper or richer tones of a color, or to combine different colors or dye properties. Cross dyeing is another variation of vat dyeing in which cloth composed of varying fiber contents is dyed. Because the different fibers accept the dye to different degrees, the fabric doesn’t emerge from the dye bath as a solid color, but instead with different colors in the areas of different fiber content. Even more complex color combinations can be achieved by combining over dyeing with cross dyeing. Other than applying solid colors, there are a variety of other coloring techniques. By far the most common is printing, which includes the techniques of block printing, roller printing, and screen printing (also known as silk-screening.) Simple to complex designs can be printed onto the surface of the fabric, using any number of different colors. Fabrics can also be hand-painted, again with any number of colors. Resist dyeing is a method in which portions of the fabric are blocked out with a dye-resisting agent or process before the piece is dyed. Complex designs can be created by repeating the resist dyeing process, building up multiple layers of color. There are a variety of methods of resist dyeing, most differing in the type of resist. Batik uses melted wax. Tie dying, a process familiar to most, relies on compressing the fabric with lengths of string. Shibori is a category of Japanese techniques in which folds, pleats, tied string, and/or stitches are used to compress the fabric. Ikat is a complex technique in which the warp yarns of a fabric are painted and/or resist dyed before the weft yarns are woven in. Dyes can also be resisted using other techniques without specific names. Once colors have been added in any of the above fashions, they can also be removed. Selective application of bleach or other color removers can create interesting color effects, particularly when the color removal process is halted before complete. Interesting effects can also be created by applying the removing agent with a paintbrush, with a sprayer, over stencils or shaped objects, or when used in combination with constriction techniques similar to tie-dyeing or shibori. It’s worth noting however that not all dyes react the same to any given color remover. Some may be easily removed and others may be resistant. © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 7 Treatments and Decorations Most fabrics are given finishing treatments during their manufacture to create special effects or to impart specific properties. By far the most common treatment is to apply sizing, a glue-like stiffening substance. Sometimes sizing is added to aid in some part of the production of the fabric, but more often it’s added to alter the appearance and texture of the fabric, in an attempt to make the fabric more marketable or appealing to the consumer. Sometimes a fabric is treated with a glaze, a shinier and more permanent variety of sizing. Whereas many sizings are expected to wash out, a glaze is intended to be an integral part of the finished effect of the fabric. Some fabrics have physical processes performed on them to affect their appearance or texture. Beetling is a process in which a fabric is hammered to produce a lustrous finish. Calendering is a process in which fabric is passed through heated rollers under high pressure, producing a smooth or glossy finish. Flannels are created by brushing the surface of a woven fabric. As the fabric is brushed, fiber ends pull loose from the yarns and form a fuzzy surface. Silvercloth is a particular variety of flannel which has been impregnated with microscopic silver particles. It’s used to construct and line cases for storing silver, as it impedes the tarnishing process. Fleece is created using the same process as for creating flannel, but applied to a knit fabric. Sometimes similar in appearance to flannel or fleece, fulled fabrics are created using the same processes used to create felt. But rather than applying these processes to loose fibers, they’re applied to a finished fabric. The fabric maintains the structure of its weave or knit, but becomes stiffer and thicker and takes on some of the properties of felt, becoming more water-resistant and fray-resistant. Sandwashing is a process in which a fabric is washed with sand. The sand abrades against the fabric in the washing process, softening it and imparting an irregular aged or distressed effect. Stonewashing is a similar process in which pumice stones are used in place of the sand. Heat or chemicals can be used to alter the surface texture or appearance of fabric. Designs can be embossed into the surface, usually on velvets or satins. Caustic chemicals can be applied in patterns to the surface of the fabric. These can cause the fabric to shrink unevenly, producing puckered fabrics such as plissé. Alternately, the chemicals can be used to selectively remove, or burn out, certain areas of the fabric. Devoré velvet is an example of a fabric created in this manner. Decoration can be applied to the surface of the fabric. Embroidery can add a variety of designs, and may incorporate yarns of varying texture, thickness, or color. It can also be combined with cutwork, producing fabrics like eyelet lace. Beads or sequins can be sewn or glued to the surface of the fabric. Flock (loose fibers) can also be glued to the fabric in designs or over large areas. Tufting is a process in which lengths of yarn are punched through the surface of the fabric, creating a pile. © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 8 Named Fabrics and Classes of Fabrics In addition to the names for the many different types of weaves and knits, there are many words for types of fabric. Sometimes these names precisely specify a fiber content and method of construction. One example is denim, which is a cotton twill. Other times the name may only define a category of fabrics with some common property. An example of this type of name is gauze. While gauze is a lightweight, sheer, loosely woven fabric, it can be made from almost any fiber. When dealing with named fabrics it’s important to remember the goal isn’t to be able to name a given fabric. That would be relatively pointless, and often not even possible, as the definitions overlap so much that many fabrics could be called by several different names. Instead, the goal is to be able to understand what type of fabric is meant when a named fabric term is used. For definitions of more named fabrics, refer to the Glossary of Fabric Terms. Once you understand the differences between the above aspects of fabrics and begin to gain personal experience with them you’ll understand how any given fabric will behave, how durable it will be, how it must be cared for, and what it will be like to work with. This knowledge will then allow you to choose the right fabrics for your projects. © 1999-2009 Jessica I. Clark Understanding Fabric - Page 9