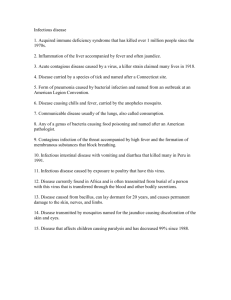

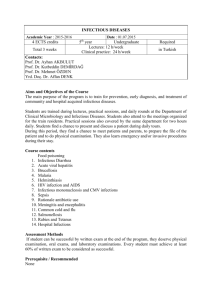

Human Infectious Diseases Response Framework

advertisement