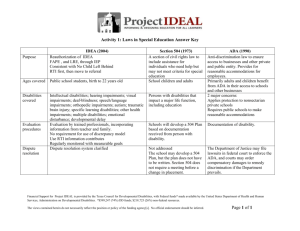

International Journal of Special Education, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2010

advertisement