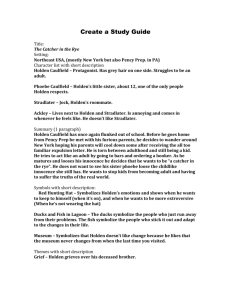

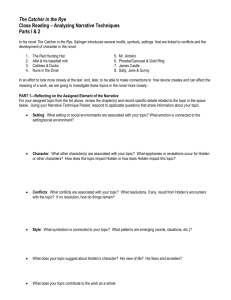

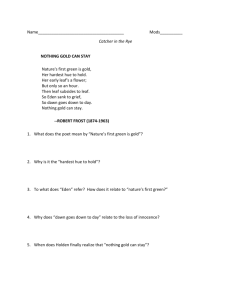

The Representation of J.D. Salinger's Views on Changes in

advertisement