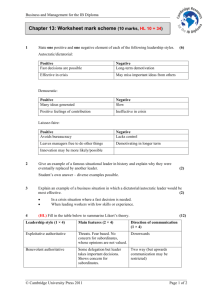

A. The measurement of negativeness

advertisement

Negative Information Communication: What Can Leaders Do Qiong Bu 1, Steven Ji-fan Ren 1 , Ming-jian Zhou 1 1 Center of Business Administration, Harbin Institute of Technology Shenzhen Graduate School, Shenzhen, China (buqiong.doc@gmail.com, renjifan@gmail.com, mngzmj@gmail.com) Abstract - This paper explores a relatively new subfield of the communication in the organization: negative information communication. We define negativeness of negative information communication. Through case study analysis, we identified several factors which managers may consider important for negative information communication, named explanation, fix and occasion. We also examined how the leadership style of leaders (as senders) influences those three factors. Besides, we proposed the moderating effect of the negativeness on the relationship above. Implications and future research are discussed. Keywords - Communication, Leadership style, negative information communication I. INTRODUCTION It may be an unpleasant but necessary part of managers' job to deliver bad news to their subordinates [1]. An improper method dealing with this could cause enormous damage, including the negative moods [2], actions and the consequent decrease of performance [3]. One of the famous cases is Neal L. Patterson's case. Patterson is CEO of Cerner Corporation, a Kansas Citybased medical software corporation. Patterson is infamous for his e-mail flaming managers for not coming to work before 8 am and leaving before 5 pm. In the e-mail, originally sent to some 400 managers at the company's headquarters, he complained managers were not working hard enough. He said: "As managers, you either do not know what your EMPLOYEES are doing or you do not CARE. You have created expectations on the work effort that allowed this to happen inside Cerner, creating a very unhealthy environment. In either case, you have a problem and you will fix it or I will replace you". Later on one of the 400 managers posted the e- mail to Yahoo, and the company's stock price fell by over 22% from a high of $1.5 billion USD [4]. The negative information, the content of which has potentially negative consequences for the recipient, weighs more heavily comparing with other information [5] . That means people spend more attention on negative information than neutral or positive information. However, the definition and the measurement of the negativeness of the negative information are rarely mentioned in previous literatures. During the process of negative information communication, the sender is and should be responsible for the negative information communication. In most common situation, the sender holds the information which is important to the receiver, while the receiver hardly knows that. That is, the process is an asymmetric one, as shown in Fig. 1 [6]. The information sender is in a dominant position before and during the interaction. In the context of the organization, the sender is usually the leader. He/she has the authority of choosing almost every changeable factor. However, the role of leader and his/her leadership style is also rarely found in former literature. Thus, by the case study, we will: 1) offer the definition and measurement of the negativeness of the negative information; 2) examine what factors the leader will choose to reduce the predicted negative reaction of the subordinates; 3) examine if the leadership style can influence the importance of the factors to the leaders; 4) propose the moderating effect of the negativeness on the relationship above. Sender Receiver Potential Behavior Change Fig. 1 The asymmetric process of communication II. LITERATURE REVIEW A. Negative Information Communication Current studies in the field of communication are mainly focus on the media [7][8], the communication satisfaction[9] and so on. Other literature which discuss the negative information communication disperse in the field of marketing [10] or psychology [11]. However, literature which studied the negative information communication as a single subfield of communication research are rarely found except the study of Sussman and her colleagues [6]. They examined which medium could increase honesty and accuracy during bad news delivering process. Their focus is on message distortion and found that e-mail is the most effective medium to reduce distortion. Their study has given insights on how electronic medium can help when delivering bad news. But they didn't provide the specific roles of the sender and the receiver. Their experimental research on the undergraduate makes the conclusion not very convictive in the context of the practical organization, especially when the sender who dominates the communication is the leader instead of the schoolmate. We believe that, the leaders and their leadership styles also play a critical role to influence the communication. Interviews in Firm A were conduct two rounds. The first round tried to collect the comprehensively related information. Therefore, most part of the interviews was free talk. Then the second round of interview was conduct to confirm some propositions extracted from former interview by focusing on some specific cases. Besides, the interviewees were also asked to fill some necessary questionnaires. All interviews were recorded to audio files. B. Leadership Style IV. CASE BACKGROUND There are multiple researches on the leadership and leadership style. The famous scholars have their own standards on the classification of leadership, any of which can describe one of aspects of the manager. Considering communicating with people is a part of emotional capabilities, we choose the Daniel Goleman's six leadership styles [12]. Daniel Goleman proposed that emotional capabilities are more important for leadership than intellectual capabilities. He identified six leadership styles, namely coaching, pacesetting, democratic, affiliative, authoritative, and coercive. This order of styles moves from very democratic via supportive to authoritative. Pacesetting and coercive is only suggested in cases of emergency, because of their inherent thread for long-term relationship between leader and follower [12]. Leaders may have more than one style, but the Affiliative and authoritative style are two typical leadership styles in practice. Affiliative leaders care about the subordinates, and are willing to develop a warm relationship with them. In another hand, authoritative leaders care the performance more than people. They probably order the subordinates instead of take counsel. Thus, studying about these two styles is representative and can be expanded to the other styles. The leadership styles offer the principles of the leaders' activities but can't be specific to communication field. Therefore, the clarification of the role of the leadership style in the process of communication is necessary for the both fields of communication and leadership style. III. METHODOLOGY The lack of related literature indicates that the study of negative information communication in organization is in its early stage, which is quite suitable for case study. This method of study is useful to deal with the complex information such as documents and interviews, and expand the explanatory and predictive power of the studied theory. Eisenhardt [13] points out that the outstanding and extreme cases should be chosen as the objects of case study, in order to extend existing theory. Following this principle, we choose Firm A as the background organization. Firm A which is seated in the north of China is a support center to deal with clients' computer stoppage, belonging to a multinational corporation. Their remote consult engineers (RCE) are at the first line which can connect with clients. Each team leader is responsible for at least one support team servicing a unique product or area. We choose two managers and three cases as the objects. The situation of cases and managers is shown in TABLE I. TABLE I THE SITUATION OF MANAGERS AND CASES Managers Manager style High Negativeness of cases Low Manager A Affiliative Case A Manager B Authoritative Case B Case C A. Managers Managers as interviewees were chosen carefully. Firstly, we interviewed some subordinates privately, asking their impression about their leaders. According to this, we focused on three managers. To confirm the leadership styles of managers, then we send the questionnaires which based on Daniel Goleman's paper [12] to managers and their subordinates. And finally two typical leaders were chosen. 1) Manager A: He is described as “a nice people”, he cares about the relationship with subordinates, and easy to get along. His and his subordinates' questionnaires show that he is willing to create harmony and builds emotional bonds, and his own summary about his leadership style is “People come first.” 2) Manager B: He is a complex leader. His own questionnaire and some subordinates' indicate he is democratic, pacesetting, coaching and authoritative, however, almost every subordinate's questionnaire contains one sign of authoritative leadership style. Thus, we consider him as an authoritative manager. B. Cases We select three typical cases in different levels of organization and the information conveyed in these cases has the different level of negativeness. 1) Case A: It's a technology support team for a data warehouse (DW) software. Because the client group continued losing, this DW software has exited the market in the year of 2010, and corresponding support will finish at the end of 2013. Manager A is responsible for this team. While communicating with his subordinates, he emphasized they could get another position as soon as this team is dismissed, and the training plan was executed. 2) Case B: During the financial crisis in 2008, the decision of cost control was executed in Firm A. However, the policy didn't work well. At the end of next year, an email was sent to every employee, in which the employees were asked to sign a voluntary agreement about pay cut. Employees who weren't willing to sign this agreement were persuaded by the direct manager and finally agreed. Manager B reports some subordinates of him couldn't accept this at that times, therefore he talked to them separately. He chose a proper occasion, including single room in the company, smoke point and the restaurant. He prepared the explanation about the situation, and encouraged the subordinates worked through the hard time with the company. 3) Case C: There is a performance assessment each month and quarter in Firm A. Managers usually need to talk to the employees whose performance wasn't desirable. Manager A and B conduct the communication in the similar way. The conversation is usually in a single room, just the manager and one subordinate. The subordinate is asked to talk about his/her recent performance, following optional praise. Then the manager shows the data of performance, and tries to figure out the reason of the undesirable consequence. The communication usually ended with the encouragement and the suggestion to improve. V. CASE ANALYSIS A. The measurement of negativeness TABLE II MEASUREMENT OF NEGATIVENESS Measurement Source Duration Time to take effect Serio usnes s shown in TABLE II. 1) Duration: We summarize this measurement from the cases. In Case A, the dismissing of the team lasts forever, that means the consequence of the negative information continuously exists. In Case C, the consequence mostly is mental and variable depending on the receiver. But in general, it lasts shortly. Case B is complex, because the pay cut is a one-off activity, it lasts until the next pay rise, which is difficult to measure. Duration indicates an aspect of negativeness: the duration of the negative consequence, the longer the duration is, the higher the negativeness is. 2) Time to take effect: We summarize this measurement from the cases. In Case B and C, the time from the communication happened to the consequence take effect is short. In another hand, the team members from Case A have three years to think about their future career. The concept of time to take effect indicates the time span from the communication to the consequence. The larger the span is, the lower the negativeness is. 3) Seriousness: The concept of seriousness has two meaning: boundary and damaged benefit, which are considered by most interviewees. Boundary means the individuals or groups involved, from individual to organization. As stated before, Case A is related to a team, while Case B is an organizational activity. Case C only involves the subordinates who don't perform well. Thus their respective boundary is middle, large and small. Another aspect of seriousness is damaged benefit, which sounds a little subjective. Although people value something in their own opinion, the benefit damaged can't be changed. We get the result about benefit damaged from subordinates, in the assumption that substance or financial benefit weights more. The weight of the measurements is different: the interviewees care the seriousness more. However, the quantitative relationship is not available in this case study. But we can get an equation with undetermined coefficients as in (1). N = α1D + α2T + α3(β1B + β2DB) Measurement in cases Case A Case B Case C Case Long N/A Short Case Long Short Short Boundary Intervi -ew Middle Large Small Damaged benefit Intervi -ew Large Large Small The word “negativeness” here means how negative the negative information is. We believe that the negativeness is the property of negative information. However, there isn't a systematic measurement of the negativeness at present. According the interviews and case study, we summarize some measuring standard, as (1) All coefficients in this equation are between 0 and 1, andα3 is greater than α1 and α2. N stands for negativeness, D stands for duration, T stands for time to take effect, B stands for boundary, DB stands for damaged benefit. The specific value of negativeness depends on the scale is five-point or seven-point. B. The leadership style influences the importance of factors to the leader We got several factors which are considered by managers before the communication, listing in the TABLE III. . TABLE III THE LIST OF FACTORS Factors Explanation Sources Manager A and B Fix Manager A Occasion Manager B Expression Manager A and B The character of subordinates Manager A and B Description “You should make your pronunciation reliable, so I will prepare some numeral data to explain the source of the information.” “I will explain the fact in detail and expect the acceptance.” “There is a factor which I can't summarize it to a word. It contains but not only limited to the compensation; it also refers to the suggestion and possible help about the further work” “According to the specific information, I choose different occasions, which are different from the media. They could be all face-to-face, but in different places and time, like meeting, personal interview, conversation at the smoking point or a restaurant. ” “The expression is important, variable by the specific circumstance.” “I pay attention on the expression and keep my eyes on the subordinates' reaction” “I must consider the endurance of the subordinates, to decide the expression.” “Understanding the feeling of the subordinates is important.” 1) Explanation: it contains the reason and the source of the information, the detail, the situation of others if it is accessible and the data which can confirm the information, such as a rank of monthly performance. 2) Fix: the compensation in another way, or the suggestion to improve, such as a promise of further promotion after the pay cut. 3) Occasion: the composite concept related to the participant, the time and the place, such as the meeting, chat in the company or in a restaurant. 4) Expression: the tone, wording or the nonverbal language and so on. 5) Character of subordinates: the temporal mental state, the endurance, the emotional intelligence and so on. The character of subordinates is critical for the successful communication. However, it's not a factor which can be controlled by the manager. The expression is controllable, but it's the dependent variable, depending on the other factors like the character and the relationship. Thus, we choose the remaining factors and imply them in the cases, as shown in TABLE IV. The circle in the table means that the factor is considered in the responding case. TABLE IV FACTORS IN CASES Factors Explanation Fix Occasion Case A ○ ○ Case B ○ ○ Case C ○ ○ By the interview, we also find that the leadership style can influence the importance of factors to the leader. The difference is shown in TABLE V. when the communication isn't related the specific cases, both A and B care about the explanation. But Manager A didn't mention the consideration on the occasion. Manager B did mention the fix, but only few times. According this situation and their different leadership styles, we suggest the proposition below: P1: the leadership style influences the importance of factors to the leader. TABLE V THE IMPORTANCE OF THE FACTORS TO LEADERS Factors Explanation Fix Occasion Manager A ○ ○ Manager B ○ ○ C. The moderating effect of the negativeness Managers were asked to sort the factors in the order of the importance in the different situation of negativeness. The result (TABLE VI) shows that when the negativeness is high, the factors which managers valued are distinguishingly influenced by the leadership style, but this difference becomes non-significant when the negativeness is low. The order is also confirmed by the cases, which can support the moderating effect of the negativeness empirically. TABLE VI THE IMPORTANCE ARRAY UNDER DIFFERENT NEGATIVENESS Negativeness High Low Manager A Fix Occasion Explanation Manager B Occasion Fix Explanation Explanation Occasion Fix Thus, we suggest the proposition below: P2: the negativeness of the negative information has the moderating effect to the relationship between leadership style and the importance of factors to the leader. Summarizing the propositions above, we propose the model, shown in Fig. 2. Negativeness Explanation P2 Leadership Style Fix P1 Occasion Fig. 2. THE PROPOSED MODEL VI. DISCUSSION Previous research suggests that the sender distorts the negative information more largely if the media is face-toface (FTF) [6]. But the phenomenon in this study is not supportive. Managers in Firm A choose to explain the information as clearly as possible, instead of distort. That is probably because of the organizational culture [14] or the quality of professional managers. Whether or not, that shows the different conclusion in an experimental or empirical environment. Another conclusion that may challenge the current theory is about the media choice. Scholars suggest media choice theories like media richness [15] and social presence [16] . But the study shows that when the information is negative, leaders unlikely choose a single media except the face-to-face. They consider the other media such as email may cause confusion or make the perceived negativeness higher. In another word, the negative information is conveyed by face-to-face in all possibility. VII. LIMITATION AND FURTHER RESEARCH Negativeness is an objective concept. It only relates to the information itself and some macroscopic factors like the culture. However, even the information with the same negativeness can lead to different reaction according to the receiver's personality. Thus, the concept of perceived negativeness is also necessary for the further research of the reaction of subordinates. In this study, we didn't check all six leadership styles, but focused on two typical styles. That offers a direction for future researches to check more styles and related factors. Besides, the study is conducted in a single firm, lacking of comparison with other companies. Although the cases and managers we choose are representative, the study about multiple firms is still necessary. As shown before, we didn't get the accurate coefficients in (1) in the situation of interview. Confirm these numbers will be the next step of research. REFERENCES [1] M. J. S. Fulk, Distortion of communication in hierarchical relationships vol. 9: Newbury Park, 1986. [2] T. L. Schuster, et al., "Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood," American Journal of Community Psychology, vol. 18, pp. 423-438, 1990. [3] R. T. Sparrowe, et al., "Social Networks and the Performance of Individuals and Groups," The Academy of Management Journal, vol. 44, pp. 316-325, 2001. [4] R. K. Nancy Flynn, E-Mail rules: a business guide to managing policies, security, and legal issues for E-mail and digital communication. New York: AMACOM, 2003. [5] T. A. L. Ito, Jeff T.; Smith, N. Kyle; Cacioppo, John T., "Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: The negativity bias in evaluative categorizations.," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 75, pp. 887-900, 1998. [6] S. W. Sussman and L. Sproull, "Straight Talk: Delivering Bad News through Electronic Communication," Information Systems Research, vol. 10, pp. 150-166, 1999. [7] G. J. G. Joon Soo Lim, "Social media activism in response to the influence of political parody videos on YouTube.," Communication Research, vol. 38, pp. 710-727, 2011. [8] M. L. Markus, "Finding a happy medium: explaining the negative effects of electronic communication on social life at work," ACM Trans. Inf. Syst., vol. 12, pp. 119-149, 1994. [9] V. Pornsakulvanich, et al., "The influence of dispositions and Internet motivation on online communication satisfaction and relationship closeness," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 24, pp. 2292-2310, 2008. [10] R. N. Laczniak, et al., "Consumers' responses to negative word-of-mouth communication: An attribution theory perspective," Journal of Consumer Psychology, vol. 11, pp. 57-73, 2001. [11] T. G. Sher, et al., "Communication patterns and response to treatment among depressed and nondepressed maritally distressed couples," Journal of Family Psychology, vol. 4, pp. 63-79, 1990. [12] D. Goleman, "Leadership That Gets Result," Harvard Business Review, vol. 78, pp. 78-90, 2000. [13] K. M. Eisenhardt, "Building Theories from Case Study Research," The Academy of Management Review, vol. 14, pp. 532-550, 1989. [14] M. S. Schall, "A Communication-Rules Approach to Organizational Culture," Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 28, pp. 557-581, 1983. [15] R. L. Daft and R. H. Lengel, "ORGANIZATIONAL INFORMATION REQUIREMENTS, MEDIA RICHNESS AND STRUCTURAL DESIGN," Management Science, vol. 32, pp. 554-571, 1986. [16] C. N. Gunawardena and F. J. Zittle, "Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer‐ mediated conferencing environment," American Journal of Distance Education, vol. 11, pp. 8-26, 1997/01/01 1997.