Colorado Football History

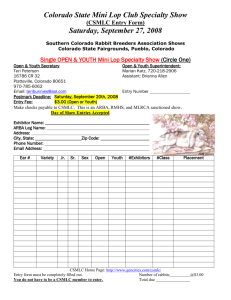

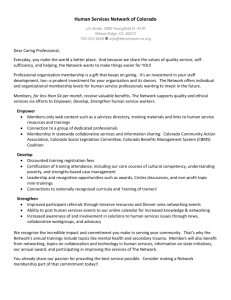

advertisement