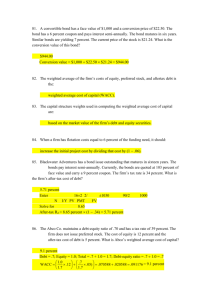

Chapter 1 Introduction to Corporate Finance

advertisement