International Portfolio Theory and Diversification

advertisement

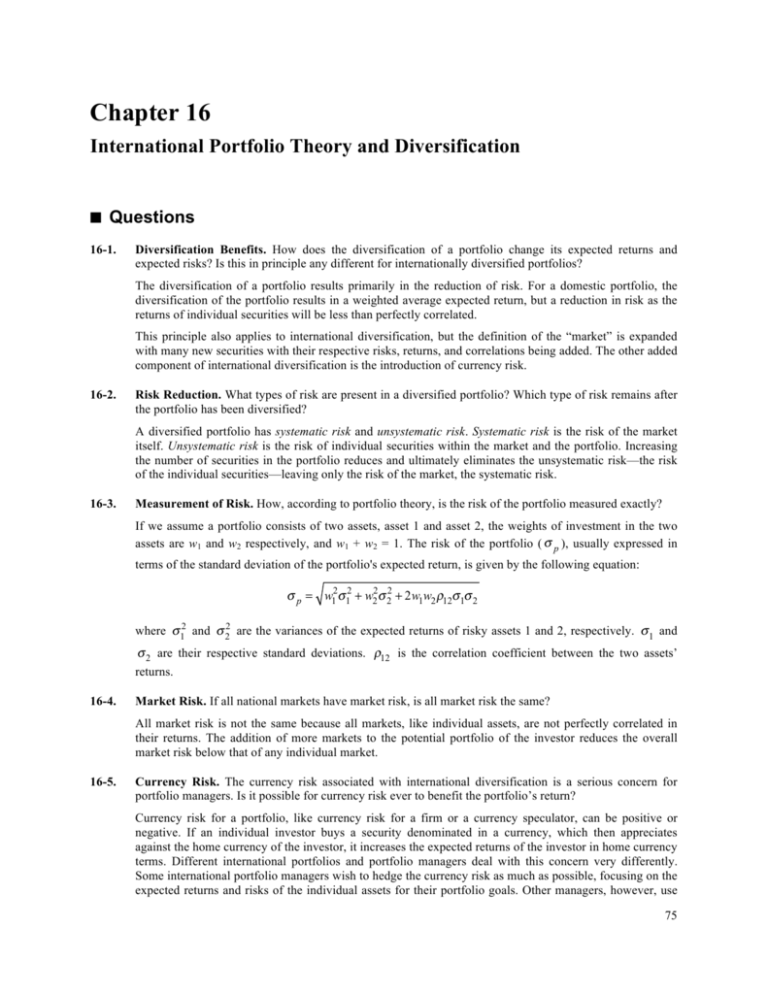

Chapter 16 International Portfolio Theory and Diversification ■ Questions 16-1. Diversification Benefits. How does the diversification of a portfolio change its expected returns and expected risks? Is this in principle any different for internationally diversified portfolios? The diversification of a portfolio results primarily in the reduction of risk. For a domestic portfolio, the diversification of the portfolio results in a weighted average expected return, but a reduction in risk as the returns of individual securities will be less than perfectly correlated. This principle also applies to international diversification, but the definition of the “market” is expanded with many new securities with their respective risks, returns, and correlations being added. The other added component of international diversification is the introduction of currency risk. 16-2. Risk Reduction. What types of risk are present in a diversified portfolio? Which type of risk remains after the portfolio has been diversified? A diversified portfolio has systematic risk and unsystematic risk. Systematic risk is the risk of the market itself. Unsystematic risk is the risk of individual securities within the market and the portfolio. Increasing the number of securities in the portfolio reduces and ultimately eliminates the unsystematic risk—the risk of the individual securities—leaving only the risk of the market, the systematic risk. 16-3. Measurement of Risk. How, according to portfolio theory, is the risk of the portfolio measured exactly? If we assume a portfolio consists of two assets, asset 1 and asset 2, the weights of investment in the two assets are w1 and w2 respectively, and w1 + w2 = 1. The risk of the portfolio ( ! p ), usually expressed in terms of the standard deviation of the portfolio's expected return, is given by the following equation: ! p = w12! 12 + w22! 22 + 2w1w2 "12! 1! 2 where ! 12 and ! 22 are the variances of the expected returns of risky assets 1 and 2, respectively. ! 1 and ! 2 are their respective standard deviations. !12 is the correlation coefficient between the two assets’ returns. 16-4. Market Risk. If all national markets have market risk, is all market risk the same? All market risk is not the same because all markets, like individual assets, are not perfectly correlated in their returns. The addition of more markets to the potential portfolio of the investor reduces the overall market risk below that of any individual market. 16-5. Currency Risk. The currency risk associated with international diversification is a serious concern for portfolio managers. Is it possible for currency risk ever to benefit the portfolio’s return? Currency risk for a portfolio, like currency risk for a firm or a currency speculator, can be positive or negative. If an individual investor buys a security denominated in a currency, which then appreciates against the home currency of the investor, it increases the expected returns of the investor in home currency terms. Different international portfolios and portfolio managers deal with this concern very differently. Some international portfolio managers wish to hedge the currency risk as much as possible, focusing on the expected returns and risks of the individual assets for their portfolio goals. Other managers, however, use 75 76 Eiteman/Stonehill/Moffett • Multinational Business Finance, Thirteenth Edition the currency of denomination of the asset as part of the expected returns and risks from which the manager is trying to profit. 16-6. Optimal Domestic Portfolio. Define in words (without graphics) how the optimal domestic portfolio is constructed. An investor may choose any portfolio of assets that lie within the domestic portfolio opportunity set. In order to maximize expected return while minimizing expected risk, the investor will find a combination of the risk-free asset available in the market with some portfolio of risky assets as found in the domestic portfolio opportunity set. The optimal domestic portfolio is then found as that portfolio which provides the highest expected return when combined with the riskless asset and the lowest possible expected portfolio risk. 16-7. Minimum Risk Portfolios. If the primary benefit of portfolio diversification is risk reduction, is the investor always better off choosing the portfolio with the lowest expected risk? The portfolio with the lowest expected risk is not the same thing as the optimal portfolio. The portfolio with minimum risk is measured only on that basis—risk—and does not consider the relative amount of expected return per unit of expected risk. Modern portfolio theory assumes that investors are risk averse, but are in search of the highest expected return per unit of risk that they can achieve. 16-8. International Risk. Many portfolio managers, when asked why they do not internationally diversify their portfolios, answer that “the risks are not worth the expected returns.” Using the theory of international diversification, how would you evaluate this statement? This means that, at least from their perspective, they do not expect that international diversification will result in any net reduction in the potential portfolio opportunity set’s risk. This is equivalent to saying that internationally diversifying the portfolio does not cause an inward shift of the portfolio opportunity set as illustrated in Exhibits 16.4 and 16.5. 16-9. Correlation Coefficients. The benefits of portfolio construction, domestically or internationally, arise from the lack of correlation among assets and markets. The increasing globalization of business is expected to change these correlations over time. How do you believe they will change, and why? Many experts have expected the correlations between markets to slowly but steadily increase over time as the world “globalizes.” There are, however, many political and institutional frictions and barriers that may cause this to be a very, very long process. One important development over the past decade complicates this process. While more and more countries have opened their markets to foreign investors and firms, more and more of the world’s publicly traded firms are listing and trading in the world’s primary equity markets of London and New York, in addition to their individual domestic equity markets. This reduces market segmentation, increases correlation, and increases liquidity. 16-10. Relative Risk and Return. Conceptually, how do the Sharpe and Treynor performance measures define risk differently? Which do you believe is a more useful measure in an internationally diversified portfolio? The Sharpe measure (SHP) defines risk as the standard deviation of the returns of the portfolio. The Treynor measure (TRN) uses a measure of risk that measures the systematic risk of the portfolio versus the world market portfolio. If a portfolio is poorly diversified, it is possible for it to show a high ranking on the basis of the Treynor measure, but a lower ranking on the basis of the Sharpe measure. The two measures provide different information, but are useful in their own ways when evaluating inadequately diversified portfolios. Eiteman/Stonehill/Moffett • Multinational Business Finance, Thirteenth Edition 16-11. 77 International Equities and Currencies. As the newest member of the asset allocation team in your firm, you constantly find yourself being quizzed by your fellow group members. The topic is international diversification. One analyst asks you the following question: Security prices are driven by a variety of factors, but corporate earnings are clearly one of the primary drivers. And corporate earnings—on average—follow business cycles. Exchange rates, as they taught you in college, reflect the market’s assessment of the growth prospects for the economy behind the currency. So if securities go up with the business cycle, and currencies go up with the business cycle, why do we see currencies and securities prices across the globe not going up and down together? What is the answer? What sounds so simple at first glance is not. First, exchange rate values change as a result of many factors (as described in earlier chapters of this book), not just business cycles. Expected changes in inflation, real interest rates, political and country risk, and current account balances, to name a few, all influence the movement of exchange rates. Second, even if business cycles were a primary driver of currency values, business cycles are not perfectly correlated globally. In fact, one way to appreciate this phenomenon is to consider that in 2001–2002 most of the major industrial economies were either in recession or near recession, but currencies still fluctuated widely. For example, the Japanese yen first depreciated against the dollar in the early part of 2002, but still appreciated significantly by mid-year. 16-12. Are MNEs Global Investments? Firms with operations and assets across the globe, true MNEs, are in many ways as international in composition as the most internationally diversified portfolio of unrelated securities. Why do investors not simply invest in MNEs traded on their local exchanges, and forego the complexity of purchasing securities traded on foreign exchanges? Actually, many investors do consider ownership in the securities of an MNE listed on their local exchange as a substitute for international diversification. Although it generates its earnings partially in different countries and currencies, its results are reported in the home currency of the parent company. The MNE bears the currency risk of “international diversification” internally, rather than the investor bearing the explicit risk of international diversification. 16-13. c. ADRs versus Direct Holdings. When you are constructing your portfolio, you know you want to include Cementos de Mexico (Mexico), but you cannot decide whether you wish to hold it in the form of ADRs traded on the NYSE, or directly through purchases on the Mexico City Bolsa. a. Does it make any difference in regard to currency risk? The currency risk is the same. b. List the pros and cons of ADRs and direct purchases. ADRs convey certain technical advantages to U.S. shareholders. Dividends paid by a foreign firm are passed to its custodial bank and then to the bank that issued the ADR. The issuing bank exchanges the foreign currency dividends for U.S. dollars and sends the dollar dividend to the ADR holders. ADRs are in registered form, rather than in bearer form. Transfer of ownership is facilitated, because it is done in the United States in accordance with U.S. laws and procedures. In the event of death of a shareholder, the estate need not go through probate in a foreign court system. Normally, trading costs are lower than when buying or selling the underlying shares in their home market. Settlement is usually faster in the United States. Withholding taxes are simpler because they’re handled by the depositary bank. What would you recommend if you were an asset investor for a corporation with no international operations or internationally diversified holdings? This would most likely not change your recommendation. If anything, it would promote ADRs over direct holdings, simply because of the domestic nature and likely structure of your own organization.