© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

11

11 CROHN DISEASE — 1

CROHN DISEASE

Susan Galandiuk, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.S.C.R.S.

The role of surgery in the management of Crohn disease has

undergone a dramatic evolution over the past 50 years.

Currently, surgical treatment of Crohn disease is seldom performed in the emergency setting; it is nearly always performed

after failed medical therapy.The decision to proceed with operative management is based on careful patient evaluation, with full

awareness of the potential complications and ramifications of

treatment. In particular, attention must be paid to the risk of

recurrent disease, the possible surgical sequelae, and the side

effects of medical therapy.

Classification

There are many systems for classifying Crohn disease. One of

the simplest is the classification developed by Farmer and associates,1 which categorizes the disease on the basis of disease location

alone (ileocolic, purely colonic, small bowel, and perianal). A more

elaborate system is the Vienna classification, which categorizes the

disease on the basis not only of location but also of age of onset

and disease behavior.2 In this system, there are four categories for

disease location: terminal ileum (L1), colon (L2), terminal ileum

and colon (L3), and any location proximal to the terminal ileum

(L4). There are two categories for age of onset: less than 40 years

of age (A1) and 40 years of age or older (A2). Finally, there are

three categories for disease behavior: nonstricturing and nonpenetrating (B1), stricturing (B2), and penetrating (B3).

Given that there are as many types and combinations of Crohn

disease as there are patients with this condition, the most sensible

approach is probably to use some combination of these two classification schemes. Careful evaluation of the specifics of each case

will yield the best treatment results; however, general classification

of the disease can help guide therapy. Broadly speaking, Crohn

disease of the small bowel has the highest recurrence rate. Because

of the important function of the small bowel in digestion, surgeons

tend to emphasize conserving small bowel length during operative

treatment of Crohn disease. Currently, however, there is an increasing focus on colon conservation with the aims of maintaining

water absorption in patients and delaying (or perhaps eliminating)

the need for a stoma.

the known risk of disease recurrence after surgical treatment of

Crohn disease and the significant associated operative morbidity. In

one single-center study, the reoperation rate for Crohn disease was

34% at 10 years.3 The agents used to treat Crohn disease can be divided into several broad groups: probiotics, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressive drugs, and biologic agents.These

can be used alone or in combination to treat disease, as well as to

maintain remission [see Table 1].

Few good studies have been done on the cost-effectiveness of

medical or surgical therapy4,5 versus that of timely surgery followed by maintenance medical therapy.There is clearly a need for

such studies.The use of potent and expensive immunomodulator

therapy (e.g., maintenance infliximab) for simple ileocolic disease

is questionable, especially in the light of studies indicating that

such treatment is not at all innocuous.6,7

CHANGING CONCEPTS IN SURGERY FOR CROHN DISEASE

Although first described in the beginning of the 19th century,

Crohn disease was not recognized as a discrete clinical entity until

the first part of the 20th century.8 At one point, it was treated surgically in much the same way as cancer, with frozen-section margins obtained at the time of resection.This approach did not yield

any substantial reduction in the recurrence rate.9 In fact, overzealous resections often resulted in Crohn patients’ requiring lifelong

parenteral nutritional support.10 Accordingly, conservative surgery

is now the rule: only gross macroscopic disease is resected into palpably normal margins (in particular, a palpably normal mesenteric

border of the bowel).

General Indications for Surgical Treatment

SIDE EFFECTS OF MEDICAL THERAPY

Significant side effects of medical therapy include those associated with failure to wean from prednisone (e.g., cataract forma-

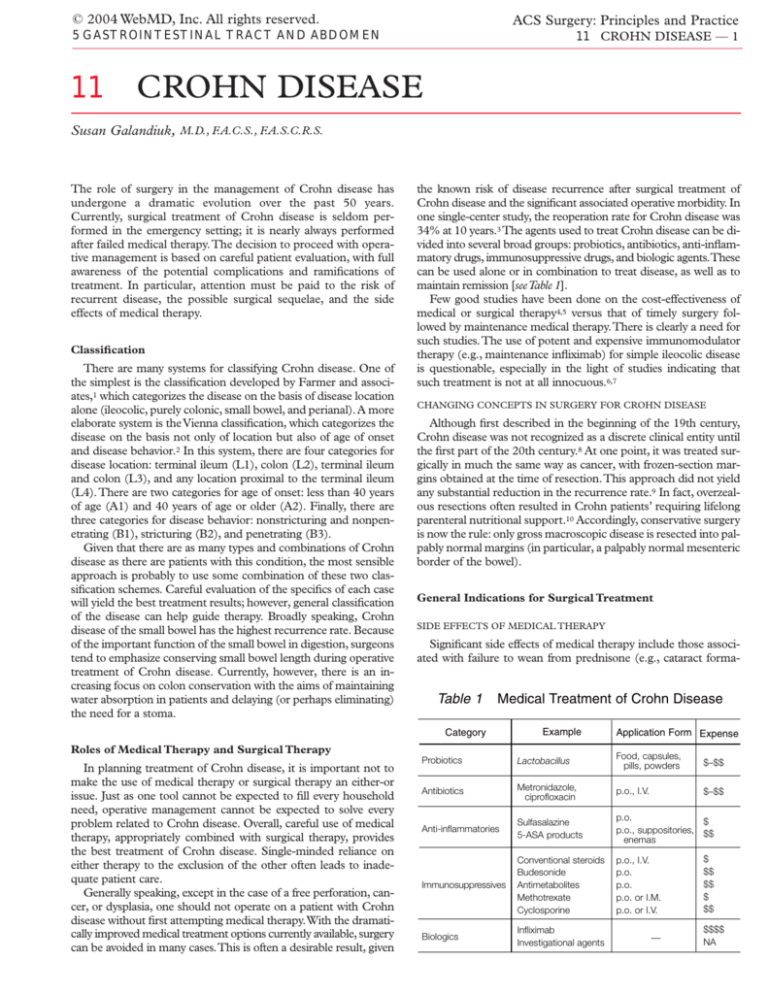

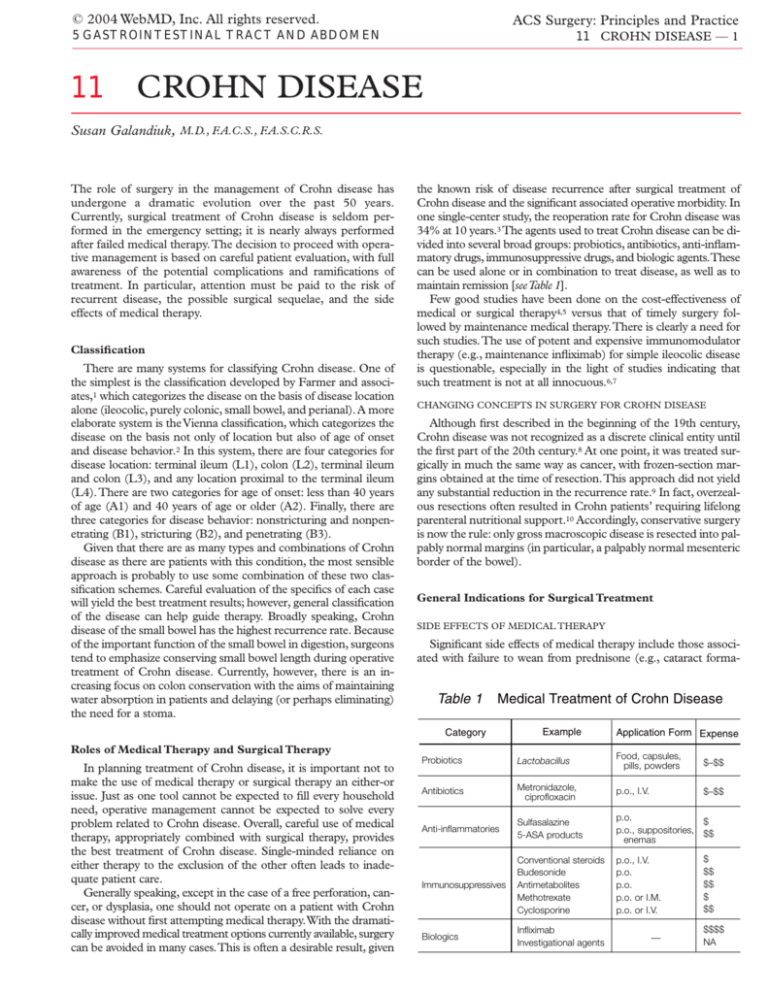

Table 1

Medical Treatment of Crohn Disease

Category

Example

Roles of Medical Therapy and Surgical Therapy

In planning treatment of Crohn disease, it is important not to

make the use of medical therapy or surgical therapy an either-or

issue. Just as one tool cannot be expected to fill every household

need, operative management cannot be expected to solve every

problem related to Crohn disease. Overall, careful use of medical

therapy, appropriately combined with surgical therapy, provides

the best treatment of Crohn disease. Single-minded reliance on

either therapy to the exclusion of the other often leads to inadequate patient care.

Generally speaking, except in the case of a free perforation, cancer, or dysplasia, one should not operate on a patient with Crohn

disease without first attempting medical therapy.With the dramatically improved medical treatment options currently available, surgery

can be avoided in many cases.This is often a desirable result, given

Application Form Expense

Probiotics

Lactobacillus

Food, capsules,

pills, powders

$–$$

Antibiotics

Metronidazole,

ciprofloxacin

p.o., I.V.

$–$$

Anti-inflammatories

Sulfasalazine

5-ASA products

p.o.

$

p.o., suppositories, $$

enemas

Immunosuppressives

Conventional steroids

Budesonide

Antimetabolites

Methotrexate

Cyclosporine

p.o., I.V.

p.o.

p.o.

p.o. or I.M.

p.o. or I.V.

Biologics

Infliximab

Investigational agents

—

$

$$

$$

$

$$

$$$$

NA

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

11 CROHN DISEASE — 2

Abscess Formation

Abscesses are particularly common with ileocolic Crohn disease. If they cannot be controlled by means of computed tomography–guided drainage, surgical therapy may be indicated.

Cancer or Dysplasia

The risk of colorectal cancer is approximately three times higher

in patients with Crohn disease than in the general population.11-13

Failure to Grow

In children, failure to grow and develop normally is one of the

main indications that medical therapy for Crohn disease has been

unsuccessful.Timely surgical therapy will permit normal development. On occasion, when bone age lags significantly behind

chronological age, treatment with recombinant human growth hormone is required.

Figure 1 Shown is an example of stenotic ileocolic Crohn disease resulting in obstructive symptoms that were not relieved by

medical therapy.

tion, aseptic necrosis of the femoral head, and weight gain). Side

effects of antimetabolite therapy include pancreatitis, neutropenia, and opportunistic infections.

COMPLICATIONS OF DISEASE

Lack of Response to Medical Therapy

Many patients with so-called toxic colitis do not respond satisfactorily to medical treatment. In severe cases of refractory disease, if surgery is not performed, colonic perforation, peritonitis,

and multiple organ failure may ensue. Such cases are much less

frequent now than they once were.

Special Considerations

PREGNANCY

Persons who have Crohn disease may be less fertile than healthy

age-matched persons. One possible explanation for this difference is

that feeling ill may result in reduced sexual desire or decreased sexual activity. Another is that pelvic inflammation caused by Crohn disease or by scarring and adhesion formation resulting from surgery

may impair fertility.To reduce the chances of the latter, hyaluronic

acid sheets may be placed around the tubes and ovaries; alternatively, the ovaries may be tacked to the undersurface of the anterior abdominal wall with absorbable sutures and thereby prevented from

entering the pelvis.

Obstruction

In many patients with Crohn disease, the behavior of the disease changes over time, from a more inflammatory and edematous process to one characterized more by fibrosis and scarring.

Whereas anti-inflammatory drugs are ideal for treating the former, surgery is frequently necessary for the latter. Failure to refer

for surgical treatment of obstruction is, unfortunately, a common

error among gastroenterologists. Severe abdominal pain is always

a warning sign of obstruction and should be taken seriously [see

5:1 Acute Abdominal Pain and 5:4 Intestinal Obstruction]. The importance of this point is illustrated by a case from my experience,

involving a patient who had obstructing ileocolic Crohn disease

with gross proximal distention of the terminal ileum [see Figure 1].

This patient lost 20 lb, was experiencing severe abdominal pain,

and was treated for more than a year with 6-mercaptopurine before

being referred for operative management. Ileocolic resection led

to rapid resolution of the symptoms.

Symptomatic Fistulas

Enteroenteric fistulas, by themselves, are no longer considered

an absolute indication for operation in the absence of other complicating factors. Symptomatic fistulas, such as those associated

with obstruction or those associated with disabling symptoms

(e.g., rectovaginal fistulas or enterocutaneous fistulas [see Figure

2]), may have to be treated surgically. Ileosigmoid fistulas, which

effectively bypass the entire colon, may be associated with profound and refractory diarrhea (i.e., ≥ 20 bowel movements/day)

and may also have to be treated operatively.

Figure 2 Shown is an enterocutaneous fistula that persisted for

more than 1 year after an ileocolic resection (arrow). The choice

of parallel incisions by the previous surgeon made selection of a

temporary stoma site much more difficult.

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

There is no evidence that pregnancy exacerbates Crohn disease;

however, there are some specific concerns that apply to pregnant

patients with this condition. Because patients with Crohn disease

often have more-liquid bowel movements, they have a particular

need for a well-functioning anal sphincter. If there is any chance of

an obstetrics-related injury (e.g., from a large baby in a primagravida or from a breech presentation), a cesarean section is advisable to minimize the risk of sphincter trauma.The same is true in

the presence of severe perianal Crohn disease. During pregnancy,

prednisone and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) medications are

safe, whereas drugs such as metronidazole are not. If imaging

studies are needed, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography are the modalities of choice.

MARKING OF STOMA SITES AND CHOICE OF INCISION

When a patient with Crohn disease is expected to need an

ileostomy [see 5:30 Intestinal Stomas], it is extremely important to

mark the site preoperatively.What looks flat when the patient is on

the operating table may not be flat when he or she is upright.The

patient must be asked to sit and lean over to confirm that the

marked stoma site is in an area without folds, creases, or previous

incisions. Stoma appliances do not adhere well to areas of previous scarring, and these should be avoided whenever possible.

Patients with Crohn disease do not react to intra-abdominal

infection in a typical fashion. It is not unusual to find unsuspected abscesses that were not revealed by preoperative CT scans and

other imaging studies. If there is even a remote chance of an

unsuspected abscess (particularly in cases of obstructing ileocolic

Crohn disease), the possibility of a temporary stoma should be

raised with the patient and the proposed stoma site marked preoperatively.

A key point is the necessity of planning for the future. Many

patients with Crohn disease will eventually require a stoma. Operating through a midline abdominal incision preserves all four quadrants for possible future stoma sites (if needed).

LAPAROSCOPY

Laparoscopic surgical techniques have gained acceptance in the

treatment of Crohn disease. In performing a laparoscopic operation for Crohn disease, it is essential to adhere to the same technical standards that apply to corresponding open procedures.

Careful intraoperative exploration of the abdomen is important, in

that many patients have multifocal disease. Without such exploration, patients may experience persistent postoperative symptoms

as a consequence of persistent proximal pathologic states that were

not addressed. As with other treatment modalities, there are some

circumstances in which laparoscopy is particularly useful and others in which it should not be used. For example, a laparoscopic

approach is ideal for fecal diversion in patients with perianal

Crohn disease.

Ileocolic resection for Crohn disease also lends itself well to a

laparoscopic-assisted approach; compared with open resection,

laparoscopic resection has been reported to result in shorter hospital stays and reduced costs.14,15 The ileocolic vessels originate

centrally, and they only lie over the retroperitoneum. Once the lateral peritoneal attachments are divided, the colon and the small

bowel mesentery can be exteriorized, and the mesentery can be

divided and the anastomosis performed extracorporeally.

Many studies have shown that even fistulizing Crohn disease

can be safely addressed laparoscopically, depending on the skill of

the surgeon. A hand-assisted approach is often useful with cases of

dense fixation, in which fistulas are common and finger dissection

may facilitate definition of the anatomy. If in doubt, one should

11 CROHN DISEASE — 3

not hesitate to convert to an open procedure.Typically, most areas

that feel fibrotic or contain fibrotic adhesions are actually areas of

fistulizing disease and should be treated as such until proved otherwise. In one study, patients with recurrent disease, those older

than 40 years, and those with an abdominal mass were more likely to require conversion to an open procedure.16

Surgical Management of Crohn Disease at Specific Sites

ESOPHAGEAL, GASTRIC, AND DUODENAL DISEASE

Crohn disease of the upper alimentary tract can be difficult to

diagnose, largely because it is relatively uncommon. Obstructing

strictures due to Crohn disease in this area are unusual; the unsuspected finding of noncaseating granulomas in biopsies of erythematous areas in a patient with Crohn disease in other locations is

diagnostic.

Occasionally, a patient with Crohn disease of the distal esophagus requires dilatations, but this is uncommon. Surgical treatment

for Crohn disease of the upper alimentary tract is almost exclusively reserved for disease affecting the duodenum. Diagnosis of

duodenal Crohn disease can be difficult and requires a certain

amount of suspicion. Frequently, the diagnosis is not made until

relatively late, because diagnostic imaging tends to focus on

endoscopy and because the degree of duodenal obstruction is

often not evident except on barium studies.The rigidity and luminal narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum is typically

much more readily apparent on contrast studies than on endoscopy. Duodenal Crohn disease can lead to gastric outlet obstruction. In children, it can be mistaken for annular pancreas.

When duodenal Crohn disease does not respond to medical

therapy, gastrojejunostomy with vagotomy is the preferred surgical

treatment.17,18 Failure to perform a vagotomy may result in marginal ulcer formation and obstruction. Some surgeons have performed duodenal strictureplasty to treat duodenal Crohn disease.

The results have been conflicting19,20; the feasibility of this operative approach is limited by the pliability of the duodenum. Many

patients experience prompt and full recovery of normal gastric

emptying after operation, but some patients with long-standing

gastric outlet obstruction continue to experience impaired emptying. The latter may benefit from administration of a prokinetic

agent (e.g., metoclopramide or erythromycin).

JEJUNOILEAL DISEASE

Short Bowel Syndrome

Although Crohn disease of the small bowel is not common and

accounts for a relatively small proportion of all cases, disease in

this area is associated with one of the highest overall recurrence

rates. Resection of large portions of the small bowel can result in

short bowel syndrome. For this reason, before proceeding with any

type of small bowel or ileocolic resection, one should measure the

length of the existing small bowel to determine the patient’s

“bowel resource.” One naturally would more readily perform a

resection in a patient who has 400 cm of normal small bowel than

in one who has only 200 cm.

Resection versus Strictureplasty

The major advance in the surgical treatment of Crohn disease

over the past quarter-century has been the technique of small

bowel strictureplasty, first proposed by Lee and subsequently popularized by Williams, Fazio, and others.17,18 Currently, the two

most prevalent strictureplasty techniques are Heineke-Mikulicz

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

strictureplasty [see Figure 3] and Finney strictureplasty [see Figure

4].The former is best suited for strictures up to 5 to 7 cm long [see

Figure 5], the latter for strictures up to 10 to 15 cm long.The sideto-side strictureplasty described by Michelassi21 is suitable for

longer areas of stricture; however, this technique involves longer

suture lines and is mainly considered for patients who already

have, or are at high risk for, short bowel syndrome.

The short, isolated strictures characteristic of diffuse jejunoileal

Crohn disease are more frequently described in patients with longstanding Crohn disease. It has been postulated that over time,

Crohn disease progresses from an edematous condition to a more

fibrotic, stricturing condition.22 It is the fibrotic strictures characteristic of the later stage of the disease that are amenable to treatment with strictureplasty. Patients with these short fibrotic strictures typically have obstructive symptoms and often are unable to

tolerate solid food, experiencing dramatic weight loss as a result.

Although strictureplasty leaves active disease in situ, it usually

leads to prompt resolution of obstructive symptoms, regaining of

lost body weight, and restoration of normal nutritional status.

a

11 CROHN DISEASE — 4

a

b

c

b

Figure 4 Finney strictureplasty. (a) This procedure is suitable

for longer areas of stricture (up to 10 to 15 cm). (b) The strictured

bowel is bent into the shape of an inverted U. Stay sutures are

placed at the apex of the U, which is at the midpoint of the stricture, and at the far ends, which lie 1 to 2 cm proximal and distal

to the stricture. A longitudinal enterotomy is made on the

antimesenteric border of the bowel with the electrocautery. A

side-to-side anastomosis is then performed, with the posterior

wall done first. (c) Shown is the completed anastomosis.

c

Figure 3 Heineke-Mikulicz strictureplasty. Stay sutures are

placed parallel to each other on the antimesenteric border of the

bowel over the area of the stricture. (a) The antimesenteric border of the bowel is then opened with the electrocautery over the

area of the stricture, and the opening is extended for approximately 1 to 2 cm on either side of the stricture. (b, c) Traction is

placed on the stay sutures, and the original longitudinal enterotomy is closed in a horizontal fashion in one or two layers.

A significant concern with strictureplasty is the possibility that

small bowel adenocarcinoma may develop; several cases have been

reported.23,24 I have treated a patient in whom a poorly differentiated jejunal adenocarcinoma developed at the site of a strictureplasty that had been performed 10 years earlier. Accordingly, many

surgeons advocate routine biopsy of the active ulcer on the mesenteric side of the bowel at the time of strictureplasty [see Figure 6].

Another concern has to do with the number of strictureplasties

that can safely be performed in a single patient in the course of a

single operation. As many as 19 strictureplasties have been performed during one procedure without increased morbidity.25

Strictureplasty can be performed with either a single-layer or a

double-layer anastomosis. It should not be performed in the presence of an abscess, a phlegmon, or a fistula; and like any other

anastomosis, it should not be performed proximal to an existing

obstruction that is not treated at the time of operation.

Areas of small bowel Crohn disease that are too long to be treated with strictureplasty can be treated with segmental resection.

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

11 CROHN DISEASE — 5

erature to suggest that the postoperative recurrence rate may be lower with a wider anastomosis.27 The anastomosis can be performed in

either one or two layers. If the bowel is thicker, a handsewn anastomosis is preferred to a stapled one.

The incidence of reoperation for recurrent disease after ileocolic resection is high and increases with the number of resections.28

Postoperative chemoprophylaxis with mesalamine can significantly reduce the recurrence rate.29 Patients who smoke should be

strongly encouraged to stop: the rate and severity of recurrence are

increased in smokers.20

Special Circumstances

Figure 5 Shown is a short fibrotic stricture that is ideally suited

to treatment with Heineke-Mikulicz strictureplasty.

The area to be resected should be as short as possible.There is no

need to obtain frozen-section margins to determine the extent of

resection; doing so leads to unnecessary loss of small bowel

length.26 The resection should extend into palpably normal areas

of small bowel. The easiest way of determining the area to be

resected is to feel the mesenteric margin of the bowel until palpably normal tissue is reached. Because Crohn disease is generally

more severe on the mesenteric side of the bowel, palpation in this

area gives the most accurate impression of the intraluminal character of the bowel. Because it is not uncommon for patients to

have multifocal Crohn disease, the entire small bowel should always be inspected at the time of operation. Operating on one area

of disease while failing to treat a more proximal lesion is clearly not

in the patient’s interest.

Because of the high rate of recurrence in patients with isolated

small bowel disease, postoperative chemoprophylaxis should be

strongly considered. In these patients, I prefer to use a more potent

agent, such as an antimetabolite, rather than a 5-ASA agent.

Ileocolic Crohn disease is often associated with intra-abdominal

abscesses or fistulas. If an associated abscess is known to be present, CT-guided drainage should be done preoperatively so that a

single-stage procedure can then be performed. If an unsuspected

abscess is identified at the time of operation, the safest approach is

to proceed with bowel resection, perform the posterior wall of the

anastomosis, and exteriorize the anastomosis as a loop ileostomy.

This loop ileostomy can then be safely closed, often without a formal laparotomy, 8 weeks after operation if there are no signs of

ongoing sepsis. If the abscess or the terminal ileal loop is adherent

to the sigmoid colon, an ileosigmoid fistula may be present. The

decision whether to resect the sigmoid colon is dictated by the

appearance and feel of the sigmoid in the involved areas. If only a

portion of the anterior colon wall is involved, that portion can be

excised in a wedgelike fashion and the excision site closed primarily. If the entire circumference of the sigmoid colon at that point is

indurated and woody feeling, a short segmental resection with

anastomosis is the best option.

ILEOCOLIC DISEASE

Approximately half of those diagnosed with Crohn disease have

ileocolic disease. Ileocolic resection is, in fact, the operation most

frequently performed to treat Crohn disease. Currently, there is a

trend toward more aggressive medical management of Crohn disease; at the same time, surgeons are seeing more complicated disease at the time of operation. These developments have implications for management. An easy ileocolic resection is an experience

that a patient generally tolerates well and recovers from very quickly; however, delaying operative management with years of aggressive medical therapy can lead to more complicated disease associated with enteroenteric fistulas, which can be difficult to treat.

Ileosigmoid fistulas are among the most common fistulas associated with ileocolic Crohn disease, along with fistulas between the

terminal ileum and the ascending colon and fistulas between the

terminal ileum and adjacent loops of small bowel.

Disease recurrence is common after ileocolic resection. Colonoscopy is the most accurate modality for postoperative surveillance and

the easiest to use; it is more sensitive than either small bowel followthrough or air-contrast barium enema. For this reason, I favor an

end-to-end anastomosis after ileocolic resection. In the event of recurrent disease, an end-to-side, side-to-end, or side-to-side anastomosis may be difficult to intubate.There is some evidence in the lit-

Figure 6 A large ulcer is nearly always present on the

mesenteric luminal border of small bowel strictures.

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

COLONIC DISEASE

Colonic involvement is present in 29% to 44% of patients with

Crohn disease.30 One of the challenges in treating colonic Crohn

disease is obtaining the correct diagnosis. Whereas Crohn disease

of the small bowel is fairly easy to diagnose, colonic disease often

is not. Because granulomas are not present in most cases of

colonic Crohn disease and because this condition can look very

similar to ulcerative colitis both endoscopically and macroscopically, differentiation between Crohn colitis and ulcerative colitis

can be difficult in the absence of small bowel or anal disease.

Colonic Crohn disease appears to be more frequently associated

with cutaneous manifestations (e.g., pyoderma gangrenosum) [see

Figure 7].

Indications for Surgical Treatment

The main indications for operative management of colonic

Crohn disease are stricture [see Figure 8], malignancy, side effects

of medical therapy, and failure of medical therapy. In children, failure to recognize and treat this condition promptly may result in

growth retardation. It is important to monitor both bone age and

insulinlike growth factor–1 levels. If these are abnormal, timely

institution of human growth hormone therapy, operative management of inflammatory bowel disease, or both may still permit normal growth and development.

Side effects of medical therapy can be substantial. They may include such varied complications as aseptic necrosis of the femoral

head and cataract formation (both related to steroid use), as well as

an increased incidence of opportunistic infections (from immunosuppression secondary to antimetabolite therapy).

Failure of medical therapy can refer to continuing severe disease

activity or, at worst, to so-called toxic megacolon. The term toxic

megacolon is actually a misnomer, in that not all patients with this

condition actually have a true megacolon [see Figure 9a]. In common usage, the term toxic megacolon refers to any condition associated with colitis that is severe enough to result in sloughing of the

a

11 CROHN DISEASE — 6

colonic mucosa; such sloughing permits endotoxins to enter the

circulatory system and evoke a septic response. The signs and

symptoms of toxic megacolon include those characteristic of sepsis—leukocytosis, fever, tachycardia, and hypoalbuminemia.These

patients are very ill and often manifest ileus, which is an ominous

development that frequently signals impending perforation. Emergency surgical intervention is required. At operation, the colon is

often distended, and when the specimen is opened, the colon may

appear almost autolytic [see Figure 9b]. In this state, the bowel frequently does not hold staples well; accordingly, it is often helpful

to sew the distal Hartmann stump between the left and right

halves of the anterior inferior rectus fascia at the lower abdominal

incision and then to close the skin over it.31 Thus, if the staple line

is disrupted, the result is essentially a surgical site infection that

can be opened and drained, rather than the pelvic abscess [see

Figure 9c] that could develop if the rectal stump were located deep

within the pelvis.

Types of Disease

Segmental disease In a 2003 review of 92 consecutive cases

of patients with Crohn colitis, the number of patients with segmental colonic Crohn disease and the number of those with pancolonic disease were nearly equal.30 Approximately 63% of those

with segmental colitis had other disease involvement as well (e.g.,

jejunoileal, ileocolic, or perianal), compared with only 12% of

those with pancolitis. The recurrence rate, however, was higher in

patients with segmental colitis than in those with pancolitis. In

addition, the risk of recurrence was higher in patients who had

granulomatous disease than in those who did not.

Pancolonic disease In cases of pancolonic Crohn disease

with associated perianal, jejunoileal, or ileocolic involvement, diagnosis is not difficult. However, most patients with Crohn pancolitis do not have other sites of disease involvement, nor do they have

granulomas.30 Consequently, differentiation of Crohn pancolitis

b

Figure 7 (a) Shown is pyoderma gangrenosum affecting the peristomal and incisional area 6 months after

creation of a loop ileostomy in a 16-year-old girl who had undergone colectomy with IPAA for a presumed

initial diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. (b) Shown is peristomal gangrenosum of the breast in an otherwise

asymptomatic patient with Crohn colitis and perianal Crohn disease who had a diverting loop ileostomy.

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

11 CROHN DISEASE — 7

a

b

Figure 8 Shown is a sigmoid colon stricture secondary to Crohn

disease that caused obstructing symptoms refractory to medical

therapy.

from ulcerative colitis can be very difficult. Many patients with

Crohn disease have been inappropriately subjected to colectomy

with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) because they were initially presumed to have ulcerative colitis.

Operative Procedures

Total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy The traditional procedure for colonic Crohn disease is total proctocolectomy

with end ileostomy, which is associated with an 8% to 15% rate of

recurrence in the bowel proximal to the stoma.32-34 This operation

remains the best choice in patients with severe rectal and anal

Crohn disease (e.g., those with so-called watering-can perineum

[see Figure 10]) and carries the lowest risk of disease recurrence. In

contrast to the approach taken in patients with rectal cancer,

which involves excising the external anal sphincter and a large portion of the levator muscles, the approach taken in those with

colonic Crohn disease is intersphincteric, with dissection performed in the plane between the internal and external anal

sphincters to reduce the size of the perineal wound and facilitate

healing. Even with the intersphincteric approach, delayed healing

of the perineal wound is common, occurring in as many as 30%

of patients.

Subtotal colectomy with ileorectal or ileosigmoid anastomosis Because many patients with Crohn disease are young,

surgeons have long been interested in operations that do not

involve an ileostomy. In the absence of significant rectal and anal

disease, subtotal colectomy with ileorectal or ileosigmoid anastomosis is an option. Unfortunately, this operation is associated with

high recurrence rates (up to 70%)35; however, with the advent of

more effective immunosuppressive and biologic therapy, it is hoped

that these rates can be reduced. As much palpably normal distal

rectum and colon as possible should be spared. The anastomosis

can be stapled, though if the bowel wall is thickened, many surgeons would feel more secure with a handsewn anastomosis in

either one or two layers.

c

Figure 9 (a) Shown is toxic megacolon in a 17-year-old girl with

Crohn colitis. The colon is massively distended and near perforation

at the time of operation. (b) When the specimen is opened, it is

apparent that large segments of the mucosa have sloughed off, leaving denuded muscle wall. (c) The distal rectosigmoid is incorporated

between the left and right halves of the anterior inferior rectus fasSegmental resection Currently, more surgeons are advocia at the lower abdominal incision and placed underneath the skin,

cating colon-sparing procedures [see 5:34 Segmental Colon Resection] which is then closed over it. Thus, in the event of disruption of the

distal stump, the contents drain harmlessly through the wound.

for Crohn disease. Although this is a relatively new approach,

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

11 CROHN DISEASE — 8

would knowingly perform in a patient with Crohn disease, every

year there are many such patients who undergo this procedure as

treatment of colonic inflammatory bowel disease that initially is

incorrectly presumed to be ulcerative colitis but later is diagnosed as Crohn disease (on the basis of either final pathologic

analysis of the resected specimen or the disease’s clinical behavior). Generally speaking, in the absence of fistulizing disease,

most of these patients are able to maintain their pouch, but they

require medical therapy for disease control.30,37-40

ANAL DISEASE

Types of Disease

Figure 10 Shown is so-called watering-can perineum secondary

to severe perianal Crohn disease.

there have already been some reports documenting the safety of

segmental resection in cases of limited disease.36 In patients with

colonic strictures resulting in obstruction, segmental resection into

palpably normal areas of the bowel yields prompt resolution of

symptoms. Because the colon performs an important water-absorbing function, many patients with a limited amount of small bowel

can still live without intravenous supplementation if a significant

segment of the colon is left in situ. However, patients with segmental Crohn disease appear to have a higher recurrence rate than

those with pancolitis, as do patients with granulomas.30 Surgical

treatment of Crohn disease continues to undergo reevaluation and

reassessment of results on the basis of the availability of newer

medical therapies.

Colectomy with IPAA Although colectomy with IPAA [see

5:33 Procedures for Ulcerative Colitis] is not an operation that one

With stenosis For patients with anal strictures that are not regularly dilated, the outlook is poor. Such strictures pose functional obstructions and typically lead to continuing problems with fistulas and

suppurative disease.They frequently become more and more fibrotic over time and often extend proximally. Most of these patients

eventually require fecal diversion. Management generally involves

self-dilation, which can often be done with Hegar dilators. If the

stenosis is not dealt with, all other treatment of the Crohn disease is

doomed to failure; obstruction at the level of the anal canal inevitably

results in the persistence of anorectal disease.

Without stenosis Anal Crohn disease without stenosis is

much easier to treat medically. Long-term oral metronidazole therapy is often helpful; other medications (e.g., anti–tumor necrosis

factor antibody) may be useful as well. Broad fissures are usually

asymptomatic. Surgical treatment should be avoided unless the

lesions are causing symptoms. Because they tend to have more liquid bowel movements, patients with Crohn disease need an optimally functioning anal sphincter; hence, fistulotomies, which

divide portions of the sphincter, should be avoided if at all possible. Placement of setons through fistula tracts can often prevent

abscess formation, provide drainage, and thereby prevent perianal

pain while minimizing sphincter trauma. Silk sutures, vessel loops,

or Penrose drains also can be used as setons [see Figure 11]. Rectovaginal fistulas pose a particular challenge. In the presence of

active Crohn disease, advancement flap repair of such fistulas has

a low success rate.41 Laparoscopic-assisted loop ileostomy improves

the success rate, but unfortunately, the fistulas may recur when

intestinal continuity is reestablished.

Postoperative Management

CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS

Figure 11 Vessel loops can be used as setons for drainage of

abscesses caused by perianal Crohn disease. They can be left in as

long as necessary and help prevent recurrent abscess formation.

In 1995, a prospective, randomized study showed that patients

who underwent ileocolic resection and were given mesalamine

postoperatively had a significant reduction in both the symptomatic and the endoscopic rate of recurrence.29 Not all of the work

done since then has confirmed these results, but several studies

and a meta-analysis have indicated that mesalamine does reduce

the postoperative recurrence rate of Crohn disease.42 Many patients undergoing surgical treatment of Crohn disease are advised to take some type of postoperative preventive medical therapy—either a 5-ASA derivative (e.g., mesalamine) or a stronger

immunosuppressive agent (e.g., 6-mercaptopurine or azathioprine). Better studies are required to document the efficacy of

the latter agents in preventing recurrence. It is hoped that

chemoprophylaxis will reduce the anticipated recurrence rates

by 30% to 40%.

© 2004 WebMD, Inc. All rights reserved.

ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice

5 GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND ABDOMEN

11 CROHN DISEASE — 9

SURVEILLANCE

BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATION

At present, there are no clear guidelines for surveillance after

operative treatment of Crohn disease. In my opinion, however,

given the increased risk of colorectal cancer in this setting,

patients with Crohn disease who retain some colon should

undergo colonoscopy every 2 years, not only to detect any

development of colonic neoplasia but also to identify any recurrence of disease in a timely manner. If recurrent Crohn disease

is detected, appropriate medical therapy should be promptly

instituted, with the aim of avoiding subsequent operation if

possible.

Exposure to cigarette smoke is known to exacerbate the symptoms of Crohn disease. Smoking has been reported to affect the

overall severity of the disease, with smokers having a 34% higher

recurrence rate and a higher rate of reoperation than nonsmokers.43-45 A 1999 study of 141 Crohn disease patients who had

undergone ileocolic resection, of whom 79 were nonsmokers and

the remainder were smokers, found that the respective 5- and 10year recurrence-free rates were 65% and 45% in smokers and 81%

and 64% in nonsmokers. The recurrence rates were higher in

heavy smokers (≥ 15 cigarettes/day) than in moderate smokers.46

References

1. Farmer RG, Hawk WA, Turnbull RB Jr: Clinical

patterns in Crohn’s disease: a statistical study of

615 cases. Gastroenterology 68:627, 1975

2. Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, et al: A

simple classification of Crohn’s disease: report of

the Working Party for the World Congresses of

Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel

Dis 6:8, 2000

3. Michelassi F, Balestracci T, Chappell R, et al:

Primary and recurrent Crohn’s disease: experience with 1379 patients. Ann Surg 214:230,

1991

4. Bodger K: Cost of illness of Crohn’s disease.

Pharmacoeconomics 20:639, 2002

5. Feagan BG, Vreeland MG, Larson LR, et al:

Annual cost of care for Crohn’s disease: a payor

perspective. Am J Gastroenterol 95:1955, 2000

6. Colombel JF, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al:

The safety profile of infliximab in patients with

Crohn’s disease: the Mayo clinic experience in

500 patients. Gastroenterology 126:19, 2004

7. Ljung T, Karlen P, Schmidt D, et al: Infliximab in

inflammatory bowel disease: clinical outcome in

a population based cohort from Stockholm

County. Gut 53:849, 2004

8. Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD:

Landmark article Oct 15, 1932. Regional ileitis:

a pathological and clinical entity. By Burril B.

Crohn, Leon Ginzburg, and Gordon D. Oppenheimer. JAMA 251:73, 1984

9. Fazio VW, Marchetti F, Church M, et al: Effect

of resection margins on the recurrence of

Crohn’s disease in the small bowel: a randomized

controlled trial. Ann Surg 224:563, 1996

10. Galandiuk S, O’Neill M, McDonald P, et al: A

century of home parenteral nutrition for Crohn’s

disease. Am J Surg 159:540, 1990

11. Greenstein AJ: Cancer in inflammatory bowel

disease. Mt Sinai J Med 67:227, 2000

12. Rhodes JM, Campbell BJ: Inflammation and colorectal cancer: IBD-associated and sporadic cancer compared. Trends Mol Med 8:10, 2002

13. Gillen CD, Walmsley RS, Prior P, et al: Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a comparison of

the colorectal cancer risk in extensive colitis. Gut

35:1590, 1994

14. Milsom JW, Hammerhofer KA, Bohm B, et al:

Prospective, randomized trial comparing laparoscopic vs. conventional surgery for refractory

ileocolic Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum

44:1, 2001

15. Young-Fadok TM, HallLong K, McConnell EJ,

et al: Advantages of laparoscopic resection for

ileocolic Crohn’s disease: improved outcomes

and reduced costs. Surg Endosc 15:450, 2001

16. Moorthy K, Shaul T, Foley RJ: Factors that predict conversion in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg

187:47, 2004

17. Murray JJ, Schoetz DJ Jr, Nugent FW, et al:

Surgical management of Crohn’s disease involving the duodenum. Am J Surg 147:58, 1984

18. Ross TM, Fazio VW, Farmer RG: Long-term

results of surgical treatment for Crohn’s disease

of the duodenum. Ann Surg 197:399, 1983

19. Worsey MJ, Hull T, Ryland L, et al: Strictureplasty is an effective option in the operative management of duodenal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon

Rectum 42:596, 1999

20. Yamamoto T, Bain IM, Connolly AB, et al:

Outcome of strictureplasty for duodenal Crohn’s

disease. Br J Surg 86:259, 1999

21. Michelassi F, Hurst RD, Melis M, et al: Side-toside isoperistaltic strictureplasty in extensive Crohn’s

disease: a prospective longitudinal study. Ann Surg

232:401, 2000

22. Marshak RH, Wolf BS: Chronic ulcerative granulomatous jejunitis and ileojejunitis. AJR 70:93,

1953

23. Jaskowiak NT, Michelassi F: Adenocarcinoma at

a strictureplasty site in Crohn’s disease: report of

a case. Dis Colon Rectum 44:284, 2001

24. Marchetti F, Fazio VW, Ozuner G: Adenocarcinoma arising from a strictureplasty site in Crohn’s

disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum

39:1315, 1996

25. Dietz DW, Laureti S, Strong SA, et al: Safety and

long-term efficacy of strictureplasty in 314

patients with obstructing small bowel Crohn’s

disease. J Am Coll Surg 192:330, 2001

26. Hamilton SR, Reese J, Pennington L, et al: The

role of resection margin frozen section in the surgical management of Crohn’s disease. Surg

Gynecol Obstet 160:57, 1985

27. Munoz-Juarez M, Yamamoto T, Wolff BG, et al:

Wide-lumen stapled anastomosis vs. conventional end-to-end anastomosis in the treatment of

Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 44:20, 2001

28. Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Pasternack BS, et al:

Reoperation and recurrence in Crohn’s colitis

and ileocolitis: crude and cumulative rates. N

Engl J Med 293:685, 1975

29. McLeod RS, Wolff BG, Steinhart AH, et al: Prophylactic mesalamine treatment decreases postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 109:404, 1995

30. Morpurgo E, Petras R, Kimberling J, et al: Characterization and clinical behavior of Crohn’s disease initially presenting predominantly as colitis.

Dis Colon Rectum 46:918, 2003

tions for primary and recurrent Crohn’s disease

of the large intestine. Surg Gynecol Obstet 148:1,

1979

33. Ritchie JK, Lockhart-Mummery HE: Nonrestorative surgery in the treatment of Crohn’s

disease of the large bowel. Gut 14:263, 1973

34. Goligher JC: The long-term results of excisional

surgery for primary and recurrent Crohn’s disease of the large intestine. Dis Colon Rectum

28:51, 1985

35. Goligher JC: Surgical treatment of Crohn’s disease affecting mainly or entirely the large bowel.

World J Surg 12:186, 1988

36. Allan A, Andrews H, Hilton CJ, et al: Segmental

colonic resection is an appropriate operation for

short skip lesions due to Crohn’s disease in the

colon. World J Surg 13:611, 1989

37. Hyman NH, Fazio VW, Tuckson WB, et al: Consequences of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for

Crohn’s colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 34:653, 1991

38. Galandiuk S, Scott NA, Dozois RR, et al: Ileal

pouch-anal anastomosis. Reoperation for pouchrelated complications. Ann Surg 212:446, 1990

39. PanisY, Poupard B, Nemeth J, et al: Ileal pouch/anal

anastomosis for Crohn’s disease. Lancet 347:854,

1996

40. Ricart E, Panaccione R, Loftus EV, et al: Successful management of Crohn’s disease of the

ileoanal pouch with infliximab. Gastroenterology

117:429, 1999

41. Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR, et al: Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1622, 2002

42. Achkar JP, Hanauer SB: Medical therapy to

reduce postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence.

Am J Gastroenterol 95:1139, 2000

43. Duffy LC, Zielezny MA, Marshall JR, et al:

Cigarette smoking and risk of clinical relapse in

patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Prev Med

6:161, 1990

44. Sutherland LR, Ramcharan S, Bryant H, et al:

Effect of cigarette smoking on recurrence of

Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 98:1123, 1990

45. Cottone M, Rosselli M, Orlando A, et al: Smoking habits and recurrence in Crohn’s disease.

Gastroenterology 106:643, 1994

46. Yamamoto T, Keighley MR: The association of

cigarette smoking with a high risk of recurrence

after ileocolonic resection for ileocecal Crohn’s

disease. Surg Today 29:579, 1999

31. Hull T, Fazio VW: Surgery for toxic megacolon.

Mastery of Surgery, 3rd ed. Nyhus LM, Baker

RJ, Frischer JE, Eds. Little Brown & Co, Boston,

1996, p 1437

32. Goligher JC: The outcome of excisional opera-

Acknowledgment

Figures 3 and 4

Tom Moore.