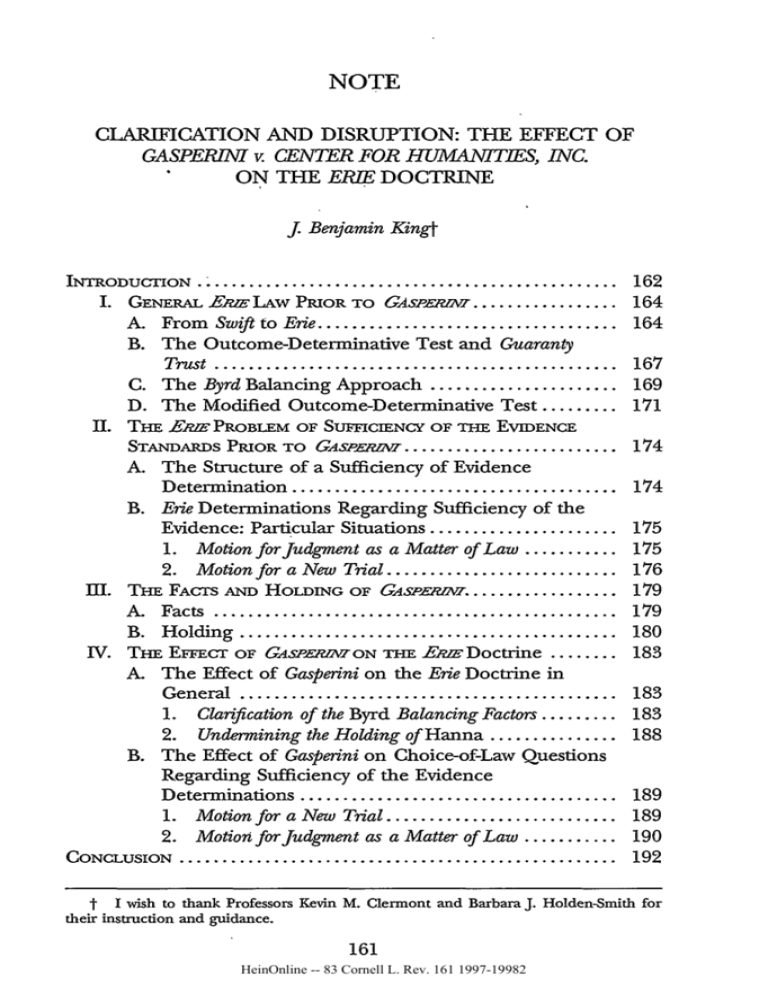

THE EFFECT OF GASPERIM v. CENTER FOR HUMANITIES, INC

advertisement