13.12.12 CA Sameer Dalal NOSCITUR A SOCLIS

advertisement

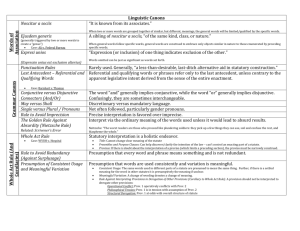

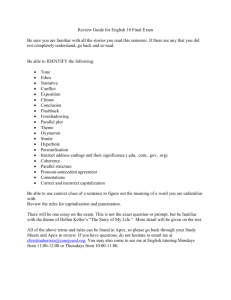

THE CHAMBER OF TAX CONSULTANTS 3, Rewa Chambers, Ground Floor, 31, New Marine Lines, Mumbai - 400 020 Tel.: 2200 1787 / 2209 0423 Fax: 2200 2455 E-mail: citcindia@vsnl.net Visit us at: Website: http://www.citcindia.org STUDY GROUP MEETING ON 13/12/2012 Prepared by: Sameer Dalal Advocate. LEGAL MAXIMS. NOSCITUR A SOCIIS – WORD IS KNOWN BY ITS ASSOCIATES OR THE COMPANY IT KEEPS This legal maxim means that, the meaning of an unclear word or phrase should be determined by the words immediately surrounding it. Lord Macmillan, explained the maxim as, “The meaning of a word is to be judged by the company it keeps.” This maxim can be used in almost any problem of construction, for it applies wherever a statutory provision contains a word or phrase that is capable of bearing more than one meaning. When two or more words susceptible of analogous meaning are coupled together, they are understood to be used in their cognate sense. The words take their colour from and are quantified by each other, the meaning of the general words being restricted to a sense analogous to that of the less general. Lord Barcon, has aptly said, coupling of word together shows that they are to be understood in the same sense and where the meaning of particular word is doubtful or obscure or where a particular expression when taken singly is inoperative, the intention of 1 the party using it may be ascertained by looking at adjoining words or at expressions occurring at other parts of the same instrument. The maxim of Noscitur a Sociis has been explained by the Privy Council in the case of, Angus Robertson v. George Day [(1879) 5 AC 63] by observing "It is a legitimate rule of construction to construe words in an Act of Parliament with reference to words found in immediate connection with them". The Apex Court in the case of, Rohit Pulp & Paper Mills Ltd. vs. CCE - [AIR 1991 SC 754] laid down the broad principle with regard to the applicability of the rule of noscitur a sociis as follows: (i) does the term in issue have more than one meaning attributed to it that is, based on the setting or the context one could apply the narrower or wider meaning; (ii) are words or terms used found in a group totally ‘dissimilar’ or is there a ‘common thread’ running through them; (iii) the purpose behind insertion of the term. Following the aforesaid principle laid down by the Apex Court, the Delhi High Court in the case of, CIT vs. Raj Kumar [(2009) 318 ITR 462 (Del)] held that the word ‘advance’ which appears in the company of the word ‘loan’ could only mean such advance which carries with it an obligation of repayment. Trade advance which are in the nature of money transacted to give effect to a commercial transactions would not, in our view, fall within the ambit of the provisions of section 2( 22 )( e ) of the Act. Similarly, Apex Court in, Pradeep Agarbatti, Ludhiana vs. State of Punjab [AIR 1998 SC 171] Entry 16 of Schedule – A to Punjab General Sales Tax Act, 1948 was in question which uses the word ‘perfumery’ in association of other words and says, “cosmetics, perfumery and toilet goods excluding toothpaste, toothpowder, kumkum and 2 soap” It was held that perfumery means such articles as used in cosmetics and toilet goods viz, sprays, etc but does not include ‘Dhoop’ and ‘Agarbatti’ Delhi Tribunal in the case of, Parsons Brinckerhoff India (P.) Ltd. vs. Asstt. DIT (Int. Tax) [(2008) 24 SOT 341 (Del)] applying the rule of Noscitur a Sociis held that, the words ‘model’ and ‘design’ used in clause (i) of Explanation 2 to section 9(1)(vi) of the Income tax Act, 1961 have to take colour from the other words surrounding them, such as, patent, invention, secret formula or process or trade mark, which are all species of intellectual property. These two words cannot, therefore, refer to drawings and designs which are sold outright, without the setter retaining any proprietary rights over them. The model or design, in order to be roped in by the provision, should be a specie of intellectual property in the same manner as a patent or invention or secret formula or process or a trade-mark. Therefore, the Tribunal concluded that an outright sale of the drawings and designs cannot fall under the definition of ‘royalty’ under Explanation 2 to section 9(1)(vi). The principle of ‘Noscitur a Sociis’ has received approval from Apex Court although its discriminate application / use has been cautioned. It must be borne in mind that the principle of Noscitur a Sociis is merely a rule of construction and it cannot prevail in case where it is clear that the wider words have been deliberately used in order to make the scope of the defined word correspondingly wider. It is only where the intention of the Legislature in associating wider words with words of narrower significance is doubtful, or otherwise not clear that the rule of Noscitur a Sociis can be usefully applied. Ref.: State of Bombay vs. Hospital Mazdoor Sabha [AIR 1960 SC 610] It can also be applied where the meaning of the words of wider meaning import is doubtful; but, where the object of the Legislature in using wider words is clear and free from ambiguity, the rule of construction cannot be applied. 3