The Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company tannery and factory

advertisement

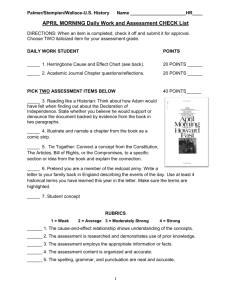

362 York Street - The Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company tannery and factory The following information on the tannery and factory is provided courtesy of Juan Estepa, Manager of Heritage and Cultural Affairs, City of Fredericton. “J. Fred Ryan constructed this 2-storey brick structure, utilized as the tanning facility, for the Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company in 1912.1 This building is located in rear of an office building on the southeast corner of York Street and situated adjacent the Canadian Pacific Railway Station. The Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company was one of three leading shoe manufacturing interests located within the tight confines of Fredericton’s industrial park. The establishment of this company proved that there was business enough for all the local shoe factories, especially given the intense rivalry between the PalmerMcLellan and John Palmer companies. The Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company was founded after principal members defected from the John Palmer Company. John Palmer, considered a tanning expert and a “pioneer in the oil tanned footwear business in Canada,”2 founded the John Palmer Company. Palmer had apprenticed in the trade from an early age and with a partner established the Brown and Palmer Tannery in 1877. Palmer was also credited with being the first in Fredericton to manufacture shoepacks.3 Under his sole direction, Palmer moved the business to Westmorland Street in 1893, at which point the company became known as Palmer’s Tannery.4 He filed for incorporation of the John Palmer Company in 1901,5 and business, which had long been on the rise, continued to increase. A cleavage occurred in the company in 1912, and John Palmer, R.W. McLellan, and W.A.B. McLellan all left the John Palmer Company.6 In rapid fashion, these parties organized a new company and sought incorporation as the Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company.7 The company proposed to build a new shoe factory within a few months of incorporation. 1 The Daily Gleaner, 23 April 1912, Tuesday, p. 8 “New Company Soon to Apply for Incorporation.” The Daily Gleaner, 25 May 1912, Saturday, p. 10 “New Company Gets Palmer-McLellan Name.” The Daily Gleaner, 29 May 1912, Wednesday, p. 8 “The New Larrigan Factory.” 2 The Daily Gleaner, 12 December 1912, Thursday, p. 3 “Fredericton’s New Industry.” 3 The Daily Gleaner, 14 December 1912, Saturday, p. 17 “Fredericton as an Industrial Centre Has Many Advantages That are Unsurpassed.” 4 Austin Squires, History of Fredericton: The Last 200 Years (Fredericton, 1980): 87. 5 The Daily Gleaner, 31 May 1901, Friday, p. 8 “John Palmer & Co.” 6 The Daily Gleaner, 21 February 1912, Wednesday, p. 8 “The Palmer Company.” The Daily Gleaner, 23 April 1912, Tuesday, p. 8 “New Company Soon to Apply for Incorporation.” 7 The Daily Gleaner, 23 April 1912, Tuesday, p. 8 “New Company Soon to Apply for Incorporation.” With plans for the new building having been completed and on display at the Queen Street office of Clements & Belyea, real estate agents, negotiations for a construction site commenced.8 Members of Palmer-McLellan suggested Queen’s Square as a potential location; however, it was the City Council that pushed for a site on York Street. There was a possibility that Queen’s Square might in the near future become the site for a Union Station.9 Shortly thereafter, Palmer-McLellan representatives expressed their preference for the York Street site. Aberdeen Street was being extended, thus situating the new factory on a corner lot. The site also had the advantage and convenience of its proximity to the railway tracks.10 J. Fred Ryan, building contractor and member of the Palmer-McLellan Board,11 broke ground for the construction of the 3-storey brick factory in June 1912.12 A series of strikes in the building trades during the summer delayed the construction of both this factory and that being erected by the John Palmer Company,13 but Palmer-McLellan’s building was completed in December 1912, ahead of the competition. The factory was built and finished by local industry. M. Ryan Brickyard had supplied the bricks for its construction, and J.C. Risteen & Company completed the interior work of the factory. The roofing, glass, and hardware had been furnished by J.S. Neill & Sons, Limited, while R. Chestnut & Sons supplied the belting. The building was divided into two sections: the tannery and the factory.14 The tannery portion of the building stood two storeys tall, whereas the factory was three storeys.15 The tannery, with its concrete floors, had been equipped with modern machinery installed by the Turner Tanning Machinery Company of Peabody, Massachusetts. Although much of the larrigan sewing was of necessity undertaken by hand, there were nevertheless a number of sewing machines that had been installed by the Singer Sewing Machine Company. Palmer-McLellan expected to produce 600 pairs per day, which would require a workforce totaling between 75 and 100 hands. When the factory opened, 30 operatives were in the company’s employ. Relations between the two companies were instantly antagonistic and a lively rivalry remained intact for many years. The newly minted Palmer-McLellan was intent on manufacturing “Palmer Brand” shoepacks and larrigans. The John Palmer Company, which produced the “Moose Head Brand” oil tanned footwear, objected to the use of “Palmer” in the corporate name.16 More importantly than that, the John Palmer Company was concerned with trademark infringement. The John Palmer Company filed suit against Palmer-McLellan insisting that the similarity in designs, particularly in catalogues, was deliberate and intended to deceive consumers. The John Palmer 8 The Daily Mail, 7 May 1912, Tuesday, p. 8/4 “Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company Asks For Concessions.” 9 The Daily Gleaner, 11 May 1912, Saturday, p. 1 “Palmer-McLellan Co Site.” In part arising from this discussion, City Council decided that it was time to secure full rights to Queen’s Square from Mrs. Twining. The City was prepared to offer Mrs. Twining $4500 for Queen’s Square. See: The Daily Mail, 7 May 1912, Tuesday, p. 8/4 “Palmer-McLellan Shoepack Company Asks For Concessions.” The Daily Mail, 14 May 1912, Tuesday, p. 8 “Protest Re Concession to New Company.” 11 The Daily Gleaner, 12 December 1912, Thursday, p. 3 “Fredericton’s New Industry.” 12 The Daily Gleaner, 4 June 1912, Tuesday, p. 8 “The New Larrigan Factory.” 13 The Daily Gleaner, 8 June 1912, Saturday, p. 10 “Another Strike in the Building Trades Expected.” The Daily Gleaner, 22 July 1912, Monday, p. 8 “Contractors are Ready for Strike.” The Daily Gleaner, 23 July 1912, Tuesday, p. 8 “22 Laborers of Building Trades Quit Work Today.” The Daily Gleaner, 24 July 1912, Wednesday, p. 8 “The Strike Didn’t Last Very Long.” 14 The Daily Gleaner, 12 December 1912, Thursday, p. 3 “Fredericton’s New Industry.” 15 The Daily Mail, 1 June 1912, Saturday, p. 8 “Building Activity in City Greatest in Years.” 16 The Daily Gleaner, 25 May 1912, Saturday, p. 10 “New Company Gets Palmer-McLellan Corporate Name.” 10 Company also requested that the rival company be barred from using the name “Palmer” especially on trademark and logos. The Court initially found in favour of the John Palmer Company, but the decision was apparently reversed on appeal. PalmerMcLellan continued to use the Palmer name in its products and in its logo.17 The Palmer name continued to resound in the shoepack business, and when in 1959 the two rival companies merged, they became known as Palmer-McLellan (United) Ltd. The reconfigured business moved to the former John Palmer factory on Argyle Street, and the vacated Palmer-McLellan factory was offered for sale.18” 17 18 The Daily Gleaner, 15 Marc h 1917, Thursday, p. 12 “Local Shoepack Companies Case in Appeal Court.” The Daily Gleaner, 17 July 1959, Friday, p. 5 “For Sale.”