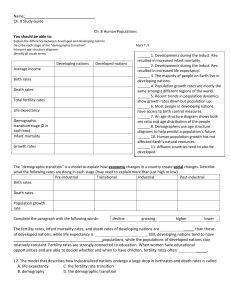

Frontiers in Population Sciences

advertisement