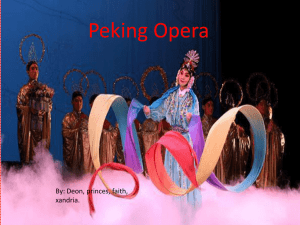

Chinese Opera

advertisement

CHINESE OPERA Photography/Opera CHINESE OPERA Photography by Jessica Tan Gudnason Text by Gong Li ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER JESSICA TAN GUDNASON was born in Malaysia and studied photography at the International Center of Photography. Her abstract platinum-palladium and color photographs have been featured in solo and group exhibitions in New York and Florida. She lives in New York. For centuries Chinese Opera companies have mesmerized audiences with their elaborately costumed and made-up characters and the pageantry and drama of their productions.Among the hundreds of regional troupes in China today, the most distinguished are the Peking, the Yue from Shanghai, and the Cantonese Operas, which are featured in this exquisite photographic volume. Photographer Jessica Tan Gudnason has been fascinated by Chinese Opera since her childhood and has spent the last decade taking breathtaking portraits of actors who perform in the fabled Peking,Yue, and Cantonese Operas. Her stunning images capturing players preparing for a role or fully dressed for a performance look more like painted sculptures than photographs. This remarkable collection of portraits range from gorgeously costumed and heavily made-up leading players to children dressing for supporting roles. Here are warriors, heroes, demons, clowns, and, the monkey king. Gudnason’s aim is to recreate the excitement, emotion, sound, color, and movement of the actors backstage from an insider’s view. Supplementing the color and black-and-white plates is an insightful introduction by actress Gong Li, who comments on these powerful photographs and provides an overview of the history of Chinese Opera, the main character types, and the significance of the costumes and makeup. The text also examines the influence of the Opera on film. Gudnason has contributed a preface describing her passion for Chinese Opera and great respect for its performers.This unique book is ideal for collectors of exceptional photography and for anyone who loves opera, music, and theater. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Gong Li is an accomplished actress who has appeared in such films Farewell My Concubine, Raise the Red Lantern, and Temptress Moon. She lives in China and makes frequent appearances at international film festivals. ALSO AVAILABLE FROM Jessica Tan Gudnason ABBEVILLE PRESS Text by Gong Li The Magic Flute Illustrations by Davide Pizzigoni Translation and Introduction by J. D. McClatchy Includes a 2-CD set ISBN --- AB B E V I L L E PR E S S Cortlandt Street New York, NY --ARTBOOK (in U.S. only) Available wherever fine books are sold. Visit us at www.abbeville.com Printed in Hong Kong ISBN 0-7892-0709-5 7 35 738 07095 6 FPO Please place hi-res art at this scale and remove this “FPO” tag. CHINESE OPERA JessicaTan Gudnason Text by Gong Li A B B E V I L L E P RE S S P U B L I S H E RS N EW YORK ■ L O N DON ■ PA RI S Foreword By Jessica Tan Gudnason y interest in Chinese opera began when I was little. My mother was an opera fan who would captivate her children by telling us about performances she had seen, and would put on a record and talk about the traditions of the art form and the stories drawn from history, legends, folk tales, and classic novels. My grandmother, who was originally from China, took my sister and me to the Chinese opera all the time. The troupe performed in a shed theater closed on three sides but open on the side facing the street.Young and old would gather together for every performance, and the stage would come alive with music, song, and fabulous costumes. It was an overwhelming experience of color, sound, and movement. For the last ten years I have been a fine arts photographer living in the United States, and have found that I still have an urgent interest in Chinese opera.I gratefully threw myself into this project eight years ago, both because of my love for the subject and because I could find only books with photographs of performances. I wanted to show the inner beauty found in backstage portraits. To come face-to-face with the actors, making small talk, and feeling the intense atmosphere in the dressing rooms became an absorbing interest.I was fascinated beyond words and at the same time learned what happens backstage.The actors rarely have much time between finishing their makeup and entering the stage, so that leaves me only a few seconds to a minute to capture the performers and whatever I could extract with my camera. I found myself busy taking all sorts of exciting photographs. It is a great feeling to work among the troupe, and the primary reason that I have made these pictures is to show the close-ups of the actors as they pull together their amazing range of talents and skills to strive for perfection onstage. As a fine-art photographer, however, I have shown what the modern eye sees at the opera:the exact attitude of the moment. Furthermore, culture and M art are important means of understanding between different nations and generations. My intention in this book is also to preserve this rich heritage so that our children may have a better understanding and appreciation of this unique tradition and performing art form. Capturing the many faces of the opera troupe backstage is the most exciting experience anyone can imagine. It is as if I am looking at the troupe from the outside, and yet I am inside taking pictures of every detail, from portraits to the makeup of each character, including costumes,hairpieces,and surroundings. My instinct is to capture as much on camera as possible. It is a race to make up for my own dwindling memory. Working backstage plunges me into a fascinating, sometimes frustrating, but ultimately rewarding world. Each time the experience is different, but always with a number of people working to prepare for the show. The main female or male roles always have an assistant or two to help with their headgear and costume. As can be seen in several photographs in this book, a large band of cloth is pulled around the forehead of the male actor to enlarge the face before makeup is applied. For the female role they apply makeup then glue the artificial bang hair to their forehead and tape up both sides of their eyes. Sometimes I’d find the performers sipping herbal tea or rehearsing lines, or a helper massaging the male lead’s shoulder while other actors help one another with their rehearsals or gossip. Once, in Beijing, I was surprised to see children as young as five to fifteen years old performing at their school.They were all great, serious actors who had been handpicked from all over China and were full of determination to be among the best.The place was full of life and activity: one young boy was alone in a room rehearsing his lines in front of the mirror; the male cast was lined up to have their heads shaved by one boy, after which another would rinse off their hair with water from a bucket. They were as curious of me as I was of them.They had never seen a female photographer, and were very anxious to see the inside of the camera while I changed my film. They were told that I came from A m e ri c a , and three little girls took my arm together with theirs and kept pointing to the skin tone. They were surprised when I told them that I was also Chinese, but living in the United States. This project gave me an opportunity to rediscover the essence of the art form, recognize the greatness of its past, and help us to foster a better understanding of this heritage and to further enrich our appreciation of Chinese opera. I greatly admire all the artists for the exquisite gift of their performances.They allowed me to create my own vision of their art and to show certain activities and moments usually not seen by the audience. Because Chinese opera culture deems that each performer must integrate his own means of communicating into the traditional demands of the role and the art form,I have tried to bring my own new vision of this ancient theater to the new world and its new millenium. Children of the Pear Garden By Gong Li t is with great pleasure that i introduce the photographs in this book,which are unequaled in the beauty and expression with which they portray the fantastically colorful tradition of Chinese opera. In these pictures one finds the full range of characters, from an elegantly appointed young princess to a warrior in splendid full kit, and an unprecedented look at the intimacy of backstage life, including young students in makeup eating a meal and accomplished actors preparing for a performance. If the centuries-old art form of Chinese opera can be said to mirror the development, reconstruction, and revival of China herself, so too do the magnificent pictures in this book. The Chi nese opera’s roots exten d back to the Tang dynasty (‒ ..) and Emperor Tang Ming Huang, who had a great love of the opera and sponsored special training schools for actors.The most famous of these schools was situated just north of the Tang capital (present-day Xian) in a pear garden.The young students who practiced their singing, dancing, and acrobatics there were called “children of the pear garden,” and more than a thousand years later the name is still occasionally applied to players in the Chinese opera.Tang Ming Huang is still remembered,too, as the patron saint of the Chinese opera, and incense is burned in front of his image before every performance. More than three hundred different regional styles of Chinese opera exist today, and they have much in common. First and foremost, all performances emphasize the actor over the sets or props: the actor’s entrance sets the stage;his costume and makeup indicate the type of character he is to play; his song begins the tale; his gestures and movements reveal the setting.All of these things he will have learned, if he was lucky, from an experienced master in the art, who in turn learned from another master, and so on, in an unbroken line to the beginning of the theater.The best actors learn, imitate, then invent and instruct in their own fashion and continue the cycle. The I actor is the living history of the opera. In every step taken, every note sung, he demonstrates the influences and traditions of those who have gone before. The roles that an actor may assume fall into four basic categories— sheng (male), dan (female), jing (painted face), and chou (clown)—which are further subdivided into more specific role types. An actor will typically devote his entire opera schooling to a single type of role within these general categories. Rarely does an actor attempt to master more than one type. Sheng, or male roles, are divided into three types. A laosheng is an older man, typically a high-ranking official or officer. He wears a long black, gray, or white beard,depending on his age. Because of his high rank,he often wears ceremonial robes embroidered with dragon designs, in the style of Ming-dynasty royalty. Another type of male role is the xiaosheng, or the young man. As seen in the love - t o rn scholar in Romance of the We s t Chamber and other dramas, he sings in a high-pitched, sometimes falsetto, voice. Because of this difficult singing style, many of the most popular actors to play this role have actually been women.A third type is wusheng.Wusheng are martial experts, military men, or bandits.Their strength is not in singing, but in powerful acrobatics. A special type of wusheng is the monkey king, Sun Wukong, who, according to the popular tale, accompanied a Buddhist monk and pilgrims as they traveled on a long journey to India to pick up Buddhist scriptures and bring them back to China. Along the way they encounter many gods,demons,and warriors that Monkey must subdue. Over a dozen different operas feature Monkey, whose antics and acrobatics make him one of the most popular characters in the repertoire.The makeup is usually simple for sheng actors—a white base with rouge around the eyes and cheeks. Wusheng may have red faces, flushed with blood, valor, or drink. Monkey and his troupe of monkeys are the exceptions, with elaborately painted simian faces. Dan, or female roles, are similarly divided.The most refined of the female role types is qingyi.A character of this type is modest and gentle, and sings beautifully in a high falsetto. She typically wears a simple but elegant costume to which are attached “water sleeves,” which can be over a yard long. A good qingyi actor can manipulate these sleeves most expertly in a variety of gestures meant to show concern, shyness, or lamentation.A more lively sort of flirtatious type is the huadan.She is the concubine, the maid,or the charming serving girl. Her costumes are generally more colorful than those worn by qingyi, and she walks with a seductive sway, often clutching a red handkerchief in her right hand. Other female roles are the laodan, or old woman, and the daomadan, or warrior woman. Dan roles are exclusively played by women, but this was not always the case. During the Qing Dynasty (‒), women were banned from performing on the stage, and men played all roles. In fact, the original meaning of dan was “female impersonator.” The jing, or painted face, role is the most striking of all the different categories. Usually a bold and powerful general or bandit leader, he wears thick-soled boots and a padded costume that makes him appear larger than life. But it is his painted face that attracts the most attention.His face may be made-up in a dizzying array of styles and colors depending on the type of character to be portrayed.The colors of the face are an outward expression of the personality of the character. To say that you “wear your emotions on your face” is literally true with jing characters.A black face indicates an honest and uncompromising character, such as the incorruptible judge Bao Zheng. A red face is that of a full-blooded,loyal warrior, like Guan Yu, the legendary hero from the classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms. General Cao Cao, the villain of the same story, wears oily white makeup to represent his crafty and evil character. Blue is often the color used for bandits, while gold and silver are reserved exclusively for supernatural characters. Many painted faces mix a variety of colors, illustrating a more complicated character. The last role type is chou, or clown.The chou may be a dim but likable fool, an insufferably annoying scholar or prince, or a cunning rascal.The chou is the only character who may improvise, ad lib, and make asides to the audience using contemporary references. Male chou are easily recognized by a small patch of white makeup applied around the nose and eyes, while female chou wear makeup that exaggerates their features to comic effect. The costumes of Chinese opera are themselves an art. Because tradi- tionally there is no stage set except for a table and some chairs,the actors and their costumes become the only focus of attention in the theater. At first this may seem like a liability to Western audiences, but once the first actors step onto the stage in their bold and vibrant costumes, all misgivings are laid to rest. Most costumes are based on styles and fashions of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), regardless of the era in which the drama is supposed to occur. Yellow robes are worn by the emperor, other bright colors by princes, ministers, and generals. Scholars wear more subdued colors, while bandits and outlaws wear black.The armor worn by soldiers is made of stiff fabric, heavily embroidered, beautifully colored, and thickly padded. A soldier in full armor with four pennants tied to his back strikes an imposing and dramatic figure.This sort of costume is ideally suited to the fierce and bold character of the jing actor, though it is also used by some sheng and daomadan actors as well. No costume is complete without an accompanying headdress, each according to the character portrayed. One of the most beautiful headdresses in Chinese opera is the phoenix tiara, worn only by an empress, princess, or imperial concubine. Its frame is decorated with jade and pearls, and tassels hang down on both sides and over the forehead.A more common but equally stunning headpiece is the military helmet worn by armored soldiers.The helmet is adorned with brightly colored velvet balls and, often, two long pheasant plumes extending from the top.These plumes are often manipulated by the actor in gesture and dance to dramatic effect. The actors’ movements are also central to the drama, and each seems to have their own steady tempo.A soldier moves across the stage to the crashing of cymbals and the banging of drums.The scholar is accompanied by the more subdued sounds of flute and strings. Every gesture imparts meaning to the drama.A laosheng quickly flicking his sleeve may indicate disgust, a jing dramatically rolling his eyes shows fury.When gesture is not enough,an actor may use a small prop to convey meaning. Carrying a horse whip indicates that the actor is on a horse, and through dance the actor pantomimes mounting, riding, or leading the horse by the reins. An oar may be used to sym- bolize traveling by boat,the actor swaying gently to the rhythm of the waves. All of the gestures and movements an actor makes have been clearly defined by convention and are known by their public. Only the best actors attempt to alter the performance, and they do so knowing that the audience may either applaud or condemn the changes. Successful alterations to a role can eventually become the way the role is taught to future players.But a performance in Chinese opera depends on more than faultless execution of movements and perfect pitch when singing. Rather, the movements and signs, the song and dance that an actor performs are only the external part of the role.The actor must also feel the role, and understand the character internally.This is quite unlike the training film and spoken drama actors receive, in which they are taught to make their internal emotions real in order to externalize them into realistic movements and dialogue. The Chinese opera actor must instead keep his external performance exaggerated but beautiful while feeling true, real emotions internally. Part of the pleasure of watching great performers is seeing them channel their internal emotions through the simplest and most standard gestures, empowering each motion with unexpected dramatic intensity. Perfecting a performance of such complexity takes a lifetime of learning. In the past, young boys were simply sold to an opera school or a specific actor under contract for as long as seven years. During that time the school would provide for the child’s basic needs and train him in the theater. Discipline was cruel, and book learning completely neglected.The students would earn their keep by performing, either in public or private engagements that the schoolmaster would arrange.Today the schools are much less severe and the education more well-rounded. Opera students typically range from seven to seventeen years old. Their day begins at five in the morning with an hour of warm-up exercises. Students then practice singing while facing the school walls, which allows them to judge and modify the quality of their own voices from the sound deflected back towards them. Breakfast is at eight, followed by stage combat training and acting and singing lessons.Senior students perform in the after- noon while junior students watch and learn. Supper is served around six and is followed by more singing and acting practice, then bed. In the past, senior students would perform in public theaters in the evening, though it is now more common for them to earn extra money in the afternoon. Some of the children training in the Chinese opera dream of achieving success not only on stage, but also on the screen. In fact, Chinese cinema owes much to the opera, and they share a long history.The first Chinese film was the 1905 adaptation of the opera Dingjun Mountain by the Peking opera actor Tan Xinpei. Opera adaptations peaked in popularity in the fifties,when Cantonese cinema was dominated by two women, Yam Kim-fai and Pak Suet-sin, who starred together in a series of romantic opera films with Yam in the sheng (male) role and Pak in the dan (female) role. Their movies remained popular for over a decade. In the 1970s many Peking opera students worked as stunt men and actors in popular new kung fu films.Among the students who went on to achieve international celebrity are Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, and Yuen Biao. Chinese opera has also proved a rich source of inspiration for cinema. I have had the pleasure of appearing in two films directed by Chen Kaige that were born out of the operatic tradition. Farewell My Concubine charts the history of China in the twentieth century through the lives of two boys in the Peking Opera—one a dan (female), the other a jing (painted face). It is a story about the very best kind of actor, who feels true emotion internally while displaying perfect form externally, and how he is ultimately unable to reconcile the internal with the external, character with self. More recently the film The Emperor and the Assassin told the popular opera tale in which a retired assassin makes a failed attempt on the life of the first emperor of China.The story originates in the first-century .. writings of Han-dynasty historian Sima Qian, and it surely would have been long forgotten had not the opera kept the tale alive and familiar to audiences across the country. Three different regional opera styles are represented in this book: Peking, Cantonese, and Yue. Each has its own unique quality. Peking opera is the most popular and widespread, and so becomes the standard to which others are compared. It has a long history and a large repertoire of plays, though many of those plays are forgotten, banned, or simply no longer performed in modern China. Most performances of Peking opera today focus on legendary or militaristic plays, which feature colorfully painted warriors and daring acrobatics. Cantonese opera, on the other hand, emphasizes singing and melodic accompaniment.Yue opera is well known for the strength of its women performers, whether they are playing male or female roles.The costumes in Yue opera are also quite distinct. Both Cantonese and Yue opera use more elaborate lighting and sets than Peking opera. But they share the emphasis on grand costumes and makeup and a similar history and fascination for the public. Now, as before a Chinese opera performance, a joss stick is lit before a shrine to Tang Ming Huang. The actors sit at their mirrors and apply powder, then rouge.Assistants unpack the great wardrobe trunks and help the actors into costume. Cymbals crash. Drums beat.The children of the pear garden await their entrance onto the stage.