PRIMARY SOURCE SET: Satire and Symbolism: The Art of the

advertisement

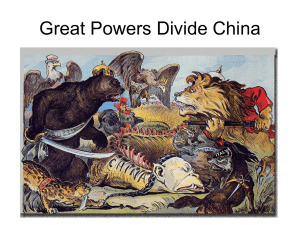

TEACHING WITH PRIMARY SOURCES—MTSU PRIMARY SOURCE SET: Satire and Symbolism: The Art of the Political Cartoon Most Americans today receive news via Facebook blurbs, 140-character tweets, or internet homepage newsfeeds. Each of these media provide news quickly, concisely, and, some may argue, efficiently. Yet, do these media inspire thoughtful reflection about the news? Do they challenge viewers to question sources? Gone are the days when most Americans read newspapers. The political cartoon is similarly on the decline. Political cartoons (small, though extremely insightful visual commentaries about important people, events, and issues) once defined American news. Thomas Nast, for example (a cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly) can be credited with (almost) single-handedly destroying the career of William “Boss” Tweed, one of the most corrupt politicians of the Reconstruction Era. Where has the cartoon gone? "Killed in committee" / J.S. Pughe. [1906, detail] While most newspapers still publish cartoons, do people (especially students) know how to interpret these visual sources? It is a question worth pondering, and a skill that will help students better analyze their increasingly visual world. This mini-exhibition seeks to help students interpret and appreciate political cartoons. Herb Block, a cartoonist who worked predominately for the Washington Post from 1929 to 2001, stated that he “often summed up the role of the cartoonist as that of the boy in the Hans Christian Anderson story who says the emperor has no clothes on.” Cartoons expose people, events, and issues for what they really are. Most cartoonists are uncivil and never fail to call out someone that is abusing their privileges, acting unwisely, or not doing their job. Cartoonists often gain either the ire or love of politicians. For instance, President Richard Nixon hated Hugh Haynie’s guts. Yet Haynie, a political cartoonist for the Louisville Courier-Journal, became a personal friend of President John F. Kennedy. While a cartoonist’s political preferences often dictate his subject material, he often tries to express values commonly held by many Americans. Sometimes he (or she) succeeds, and sometimes he fails. The following cartoons are meant to be enjoyed and examined with the knowledge that each, according to Block, “should have a view to express...some purpose beyond the chuckle.” BACKGROUND AND SUGGESTIONS FOR TEACHERS The following is a content-rich primary source set in the format of a “mini-exhibition.” It focuses on political cartoons that appeared between the end of the U.S. Civil War and the end of World War I (18671920). The purpose is for students to appreciate the subtle arts of satire and symbolism and the political and emotional power of the visual image. That purpose in itself satisfies TN Social Studies Standards US.4, 8, and 22 and Visual Art Standards 3.1, 3.3, and 4.1 for Grades 9-12, not to mention ELA standards. In order to help focus student thinking, each cartoon is accompanied by a thought question. Another purpose is to expose students to historical content. To assist with lesson planning, each cartoon is accompanied by its correlating TN Social Studies Standard. Twenty of the first thirty high school social studies standards (US.3-6, 8-9, 12-16, 18-20, 22, 2427, and 29) are covered in this primary source set. Each cartoon also has a caption that provides helpful information. While this primary source set can be used to create lesson plans about political cartoons, it works best as a supplemental resource. Teachers can use a single cartoon as a warm-up activity or a quick formative assessment. 1 The Massacre at New Orleans [US.3] In Thomas Nast’s 1867 cartoon, a white-supremacist group fires into a crowd of African Americans. President Andrew Johnson, a king with a broken crown, takes cover in a building. Graffitied on the wall beside Johnson are the following statements: “Treason is a crime, Traitors must be punished, I am your Moses” and “The time will come…when it will be proved who is your best friend.” Time certainly proved that Johnson was not an ally of the nation’s freed slaves. He favored leniency toward former Confederates, opposed the extension of the Freedmen’s Bureau, and vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Thought Question: Why did Nast choose to portray Johnson as a king, and, what’s more, a broken king? A Group of Vultures Waiting for the Storm to Blow Over—”Let Us Prey” [US.4] This cartoon, drawn by Thomas Nast in 1871, depicts William “Boss” Tweed and his cronies as vultures. Tweed (the fat, balding vulture in the center) gained notoriety as the boss of New York City’s Tammany Hall (the Democratic Party headquarters). City officials jailed Tweed in 1873 for embezzling over $50 million of public funds. In the cartoon, Tweed and his cronies stand atop the corpse of a man labeled New York. Scattered around the nest is a muzzle labeled “for the press” and bones labeled suffrage, justice, law, liberty, rent-payer, tax-payer, and New York City Treasury. As a storm rages in the background, Tweed tells his fellows: “Let us Prey.” Thought Question: What can be implied by the word “Prey”? A New Bull in the Ring [US.4] In Friedrich Graetz’s 1882 cartoon, an anonymous third party (represented by a bull) makes short work of the Democratic and Republican Parties. Both parties struggled to distance themselves from allegations of corruption. The Crédit Mobilier Scandal, arguably the most infamous case of Republican corruption, involved government oversight of the transcontinental railroad. Federal officials paid the Union Pacific Railroad to lay a portion of the track. Thomas Durant, president of the Union Pacific, dubiously subcontracted the work to his own construction company (named Crédit Mobilier). The case became national news when information leaked that Congressmen charged with allocating funds to the transcontinental railroad were, in collusion with Durant, making money off of it. Thought Question: Why is Samuel Tilden riding backwards on the Democratic donkey? 2 Which Color is to be Tabooed Next? [US.9] Chinese immigrants arrived in America as early as the 1840s and played an important role in the construction of the transcontinental railroad. White Americans passed laws that banned men from braiding their hair (a Chinese custom), refused to allow Chinese children into public schools, and restricted the Chinese from testifying in court against white people of any nationality. The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed in 1882, even barred Chinese immigrants from entering the United States. In Thomas Nast’s 1882 cartoon, an Irishman (left) and a German (right) muse over the intent of the Chinese Exclusion Act. “If the Yankee Congress can keep the yellow [Chinese] man out,” asks the German, “what is to hinder them from calling us green and keeping us out too?” Thought Question: What does the German character mean by the word “green”? Are there others that could be called green? The Tournament of Today—A Set-to Between Labor and Monopoly [US.6] Friedrich Graetz’s 1883 cartoon depicts a one-sided jousting match. The golden knight is the assumed victor. His horse’s armor is labeled “monopoly,” his helmet’s plume “arrogance,” his shield “corruption of the legislature,” and his lance “subsidized press.” His armored horse (which resembles a train) is a clear reference to his benefactor, railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who sits with fellow monopolists in the box seats behind the knight. The presumed loser of the match is a ragged man named “Labor,” who wields a useless sledgehammer labeled “strike” and rides a dying horse named “Poverty.” Thought Question: Why does Graetz use a metaphor of a medieval joust for this confrontation? Illinois—The Anarchist-Labor Troubles in Chicago [US.15] Shortly after the Civil War, wage-earners (accustomed to twelve- or fourteenhour workdays) formed the National Labor Union to advocate for a law that mandated an eight-hour workday. Terrence Powderly’s Knights of Labor, formed in 1869, soon overshadowed the National Labor Union. The Knights continued to push state and national legislatures to adopt an eight-hour workday. A workers’ strike against Chicago’s McCormick Reaper Works in 1886, however, destroyed public support for the Knights. Striking workers clashed with strikebreakers in Haymarket Square, and a surprise explosion killed seven police officers. The public accused the Knights of anarchy and hailed the police as heroes. C. Bunnell’s 1886 cartoon is illustrative of the widespread sympathy for the police. The Knights (as well as their call for an eight-hour workday) dissolved shortly after the Haymarket Riots. Thought Question: There are no typical “cartoonish” elements to this illustration. It looks like it could have been a photograph. Does this fact make the illustration more, or less, effective? 3 Granger Shirt [US.12] This undated and unaccredited cartoon breaks down the political philosophy of the Grangers, a group of financially struggling farmers. On the right-hand side of the illustration, a former monopolist’s railroad station falls apart for lack of use. On the left-hand side, Grangers busily load their goods onto a locomotive operated by the “Cheap Transportation Line.” Near the center of the illustration, a Granger on his way to Cheap Lines is stopped by three well-dressed men (presumably representatives of the former monopolist) who encourage him to ship his good via the monopolist’s locomotive. The Granger, holding up his whip and pointing at Cheap Lines, refuses their offer. Thought Question: Why does the cartoonist illustrate the situation in such stark terms? “Independence Day” of the Future [US.18] In Charles Jay Taylor’s 1894 cartoon, a group of women (wearing top hats) march in single-file behind a row of women on bicycles and a row of police officers carrying brooms. The marchers carry flags that read “United Order of Matinee Women” (a likely reference to speechmaking, as in a matinee presentation) and “Higher Culture Division.” The group marches between two statues. The statue on the left is dedicated “to the memory of the first woman who wore breeches [i.e. pants],” and the statue on the left reads “the American bird is a hen eagle and lays eggs.” Once the women pass beyond the statues, the marchers presumably encounter the President of the United States, doffing her hat to the adoring crowd. In the foreground, three women ring a bell labeled “Equal Rights.” A nearby sign reads “Strikeout the word man.” Thought Question: How does Taylor feel about the women’s suffrage movement? Why does an illustration make his point better than a written explanation? The Yellow Pest—Putting Its Nose into Everything [US.22 and 24] New York newspaper magnates Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst competed for national circulation. Both jumped at the opportunity to use tensions between America and Spain (in the build-up to the Spanish-American War) to increase sales. Pulitzer's and Hearst’s reporters turned in sensational stories. Despite the fact that reporters often based their claims on insufficient or secondhand evidence, the public accepted the newspaper articles as truth. Many speculate that Pulitzer and Hearst’s articles (especially those which accused Spain of intentionally destroyed the USS Maine) encouraged President William McKinley to go to war with Spain. After all, Pulitzer and Hearst could claim, a war is good for circulation. Their emphasis on sales and subjective stories inspired the public to call Pulitzer and Hearst’s methods “yellow journalism.” In Louis Dalrymple’s 1898 cartoon, Pulitzer (holding a folder labeled “Yellow Journal War Plans”) sticks his nose into President’s McKinley’s “War Policy.” Thought Question: Why does Dalrymple elongate Pulitzer’s nose? How else does he portray Pulitzer and how does this reveal his opinion of him? 4 Killed in Committee [US.13] John S. Pughe’s 1906 cartoon depicts spidery U.S. Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, a Republican and the chair of the Senate Finance Committee, catching and stopping finance bills (one labeled “anti-trust bill”) that he does not like. Aldrich is presumably protecting the Standard Oil tower behind him. Aldrich was close friends with John D. Rockefeller, Sr., the head of the Standard Oil monopoly. In fact, Aldrich’s daughter, Abby, married Rockefeller's son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Thought Question: Why is Aldrich portrayed as a spider and a bill depicted as a fly? What does this say about Congressional Committees? The Real Packingtown—If You Let the Packers Tell It [US.16 and 19] Louis Glackens’ 1906 cartoon satirically depicts a typical day at a meatpacking facility. In this portion of the cartoon, subtitled the “cooling room,” sheep, hogs, and cattle relax in chairs, drink iced tea, eat ice cream, and drink milkshakes. Glackens’ cartoon makes fun of meatpackers' attempts to persuade the public that their facilities are clean and humane. In 1906, muckraker Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, an exposé of the unsanitary practices of the meatpacking industry. The book, an immediate bestseller, encouraged Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Federal Meat Inspection Act. Thought Question: Glackens gives free reign to his imagination in this cartoon. How does this affect the cartoon’s impact? The Busy Showman [US.25] In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Navy to build sixteen battleships and take the “Great White Fleet” on a fourteen-month tour of the globe. Roosevelt wanted to “demonstrate to the world America’s naval prowess.” With the exception of Italy and Gibraltar, the fleet bypassed Europe but made frequent stops in areas like Peru, China, and the Philippines, countries politicians of the time might consider colonizing. William Allen Rogers’ 1906 cartoon certainly leaves the impression of ulterior motives but reassures readers “You need anticipate no so-called ‘entanglements’ as the result of this Exhibit.” Rogers’ cartoon depicts Roosevelt at the head of the fleet carrying his famous “Big Stick,” an allusion to his foreign policy. Rogers’ fleet, not really ships at all, are heavily armored elephants, a reference to Roosevelt’s Republican Party. Thought Question: What is Rogers’ opinion of Roosevelt’s foreign policy? What imagery does Rogers’ use to portray it? 5 Some Things Mr. Bryan Might Do [US.5 and 24] This portion of Louis Glackens’ 1908 cartoon depicts “some things Mr. Bryan might do” after retiring from politics. William Jennings Bryan could open a museum that pays tribute to his colorful career. In the cartoon, Bryan dusts off a gold bug, crown of thorns, cross of gold, and a “16 -to-1” silver medallion (all testaments to his fight for a silver-backed currency system). He also dusts off an octopus (a symbol of the corrupt monopolies he attempted to destroy) as well as a Filipino and an imperial crown (references to his opposition to American expansion during the Spanish-American War). Thought Question: Why would Glackens suggest that Bryan open up a museum? Examine the rest of the cartoon. What does Glackens think of Bryan? Child Power [US.14] Winsor McCay’s 1913 cartoon appeared amid the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) investigations, conducted from 1908 to 1924. The NCLC examined the poor working conditions of children on newspaper staffs and farms and in cotton mills and mines. Child labor was a touchy subject, and most businesses did not respond well to NCLC’s investigation. Lewis Hine, an NCLC photojournalist, often pretended to be a traveling salesman to gain permission to enter factories. More often than not, however, company owners denied Hine entry. McCay’s cartoon depicts children as the water flowing over a water wheel. The cartoon has two messages. The more obvious message is that children’s labor turns the wheels of industry. The other message, a reference to the children’s ghostly appearance, is an allusion to how many seemingly nameless children worked, died, and disappeared within the factories. Thought Question: What is the gender of most of the people pictured? Why so? The Tariff Triumph of Pharaoh Wilson [US.20] In Udo J. Keppler’s 1913 cartoon, President Woodrow Wilson (an Egyptian pharaoh) rides on a chariot drawn by a donkey, the symbol of his Democratic Party. Wilson’s “captives” grovel on the ground behind him: a man labeled “monopoly,” a Republican elephant, and a bull moose (a reference to Theodore Roosevelt’s third party). Wilson’s army, led by generals Underwood and Simmons, march in single-file in the top right-hand corner of the illustration. The allusion to Wilson’s victory, and the involvement of Underwood and Simmons, references the 1913 Underwood-Simmons Tariff, the first reduction of a national tariff (a tax on foreign goods) since the end of the Civil War. A lower tariff allowed for more foreign competition and lowered prices for American consumers. Thought Question: What does the rooster represent? Why might the rooster be included in a cartoon on tariffs? 6 Without Warning [US.26 and 27] In 1915, amid the Great War in Europe, a German submarine torpedoed and sunk the Lusitania, a British cruise liner, en route from New York City to Liverpool, England. Of the 1,195 passengers that died, 123 were American. The German attack did not come as a complete surprise. German officials announced their intentions to sink any British vessel involved in the war (the Lusitania was reported to be carrying war materials). While the sinking of the Lusitania upset many Americans, it did not inspire a pro-war movement. President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan, did, however, resign for fear that the event would launch America into war. In 1916, Wilson publicly demanded Germany stop their submarine warfare. The Germans refused. In 1917, J.H. Cassel illustrated this cartoon of the sinking of the Laconia. A German mailed fist is shown stabbing the ship “without warning.” By 1917, Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare wore on Americans’ patience and contributed to Congress’ decision to declare war in April. Thought Question: Were the submarine attacks “without warning?” Why would Cassel choose to leave out some of the facts? Time to Shoot [US.26 and 27] Many Americans did not want to get military involved in Europe’s Great War and reelected President Woodrow Wilson in 1916 on the slogan “he kept us out of war.” After taking office, however, Wilson found it increasingly difficult to remain neutral. In January 1917, American officials intercepted a message from the German Foreign Minister, Arthur Zimmerman, to Germany’s ambassador to the United States. The so-called Zimmerman Telegram informed the German ambassador about a possible German, Japanese, and Mexican military alliance against the United States. Wilson severed diplomatic relations with Germany in February, let the Zimmerman Telegram go public in March, and asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April. William Allen Roger’s 1917 cartoon shows an army of rats sporting German helmets and iron crosses (the German equivalent to a U.S. Medal of Honor) preparing to slip aboard an American ship. On the left-hand side of the cartoon, Uncle Sam prepares to shoot. Thought Question: Why did Rogers depict the Germans as rats? If We Were In the League of Nations [US.29] On November 11, 1918, Germany surrendered, and the Great War ended. Many Germans surrendered under the conditions of President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, one of which stipulated a League of Nations that would operate as a sort of arbitration group in the event of an international dispute. The sticking point, however, came in the requirement that League members respond to an attack on fellow League members. Henry Cabot Lodge, the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman, argued that the League’s requirements would result in costly and undesired entanglements with other countries. Lodge proved persuasive, and the United States never joined the League. In this 1920 cartoon, Winsor McCay imagines what it would be like for the United States to be in the League. John Bull (a symbol of Britain) calls down from the ship, “Hi, Sam! Send me over a new army!” Uncle Sam does not reply as he watches the American wounded march out onto the dock. Thought Question: How is a visual more powerful than words? 7 CITATIONS (If not specified, the access date for each of the following is November 23, 2015.) Nast, Thomas. “[The massacre at New Orleans].” Illustration. 1867. From Library of Congress, Cartoon Drawings: Swann Collection of Caricature and Cartoon. http://www.loc.gov/item/2009617747/. Richard Zuczek, editor. Encyclopedia of The Reconstruction Era. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006. Nast, Thomas. “A group of vultures waiting for the storm to "Blow Over" - "Let Us Prey" / Th Nast.” Illustration. Harper’s Weekly, September 23, 1871. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/00649771/. Library of Congress. “Boss Tweed Escaped From Prison December 4, 1875.” America’s Story from America’s Library. Accessed on November 24, 2015. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/jb/recon/jb_recon_boss_1.html. Richard Zuczek, editor. Encyclopedia of The Reconstruction Era. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006. Graetz, Friedrich F. “A new bull in the ring / F. Graetz.” Illustration. Puck, April 19, 1882. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2012645644/. Public Broadcasting Systems. “The Crédit Mobilier Scandal.” American Experience: Transcontinental Railroad. Last modified 2013. Accessed November 23, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/tcrr-scandal/. Nast, Thomas. “Which color is to be tabooed next? / Th. Nast.” Illustration. Harper’s Weekly, March 25, 1882. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/91793231/. Library of Congress. “Chinese Immigration.” Immigration: Chinese. Accessed on November 24, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/ teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/chinese.html. Graetz, Friedrich F. “The tournament of today - a set-to between labor and monopoly / F. Graetz.” Illustration. Puck, August 1, 1883. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2012645501/. Bunnell, C. “Illinois - The anarchist-labor troubles in Chicago / from a sketch by C. Bunnell.” Illustration. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Mary 15, 1886. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/96506762/. Library of Congress. “8-Hour Work Day.” Today in History: August 20. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ ammem/today/aug20.html. “Granger shirt.” Illustration. n.d. From Library of Congress, Popular Graphic Arts. http://www.loc.gov/item/2003688766/. Taylor, Charles Jay. “Independence Day" of the future / C.J. Taylor.” Illustration. Puck, July 4, 1894. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2012648736/. Dalrymple, Louis. “The yellow pest - putting its nose into everything / Dalrymple.” Illustration. Puck, July 6, 1898. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2012647578/. Library of Congress. “The Spanish-American War: The United States Becomes a World Power.” Teacher’s Guide Primary Source Set. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/primarysourcesets/spanish-americanwar/pdf/teacher_guide.pdf. Pughe, John S. “"Killed in committee" / J.S. Pughe.” Illustration. Puck, May 16, 1906. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2011645891/. United States Congress. “Aldrich, Nelson Wilmarth, (1841-1915).” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Last modified 2015. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=a000083. Glackens, Louis M. “The real packingtown-- if you let the packers tell it / L.M. Glackens T.G.” Illustration. Puck, July 4, 1906. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2011645916/. Library of Congress. “Upton Sinclair, The Jungle (1906).” Books that Shaped America. Accessed November 24, 2015. http:// www.loc.gov/exhibits/books-that-shaped-america/1900-to-1950.html. Rogers, William Allen. “The busy showman.—III.” Illustration. Harper’s Weekly, February 3, 1906. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2010645507/. 8 Library of Congress. “Topics in Chronicling America—Theodore Roosevelt’s ‘Great White Fleet”’. Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room. Last modified May 2, 2013. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/rr/news/topics/ greatfleet.html. Glackens, Louis M. “Some things Mr. Bryan might do / L.M. Glackens.” Illustration. Puck, November 25, 1908. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2011647373/. Library of Congress. “William Jennings Bryan and His Principles.” America’s Story from America’s Library. Accessed on November 24, 2015. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/bryan/aa_bryan_stand_1.html. Library of Congress. “William Jennings Bryan and the Free Silver Movement.” America’s Story from America’s Library. Accessed on November 24, 2015. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/bryan/aa_bryan_silver_1.html. McCay, Winsor. “Cartoon,” Illustration. Circa 1913. From Library of Congress, National Child Labor Committee Collection. http:// www.loc.gov/item/ncl2004002838/PP/. Library of Congress. “Background and Scope.” National Child Labor Committee Collection. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/nclc/background.html. Keppler, Udo J. “The tariff triumph of pharaoh Wilson / Keppler. Illustration. Puck, October 1, 1913. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2011649632/. Public Broadcasting Systems. “Wilson—A Portrait: Legislative Victories.” Woodrow Wilson: The Film and More. Last modified 2001. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/wilson/portrait/wp_legislate_02.html. Cassel, J. H. “Without warning!” Illustration. Evening World Daily Magazine, February 28, 1917. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2002714581/. Library of Congress. “William Jennings Bryan and His Principles.” America’s Story from America’s Library. Accessed on November 24, 2015. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/bryan/aa_bryan_stand_1.html. Public Broadcasting Systems. “WWI Timeline: 1916.” The Great War and the Shaping of the 20th Century. Last modified 1996. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/greatwar/timeline/time_1916.html. Library of Congress. “The Lusitania Disaster.” Newspaper Pictorials: World War I Rotogravures, 1914-1919. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/collections/world-war-i-rotogravures/articles-and-essays/the-lusitania-disaster/. Rogers, William Allen. “Time to Shoot.” Illustration. New York Herald, November 21, 1917. From Library of Congress, Cabinet of American Illustration. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010718782/. Library of Congress. “Topics in Chronicling America—The Zimmerman Telegram.” Newspaper and Current Periodical Reading Room. Last modified September 23, 2014. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/rr/news/topics/ zimmerman.html. Library of Congress. “Woodrow Wilson: A Resource Guide.” Web Guides. Last modified August 7, 2014. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/presidents/wilson/memory.html. McCay, Winsor. “If we were in the League of Nations.” Illustration. Star Company, 1920. From Library of Congress, Miscellaneous Items in High Demand. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2002714590/. Public Broadcasting Systems. “Wilson—A Portrait: League of Nations.” Woodrow Wilson: The Film and More. Last modified 2001. Accessed November 24, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/wilson/portrait/wp_league.html. Library of Congress. “Henry Cabot Lodge Was Born May 12, 1850.” America’s Story from America’s Library. Accessed on November 24, 2015. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/jb/reform/jb_reform_lodge_1.html. 9