Complements or Substitutes? Private Codes, State

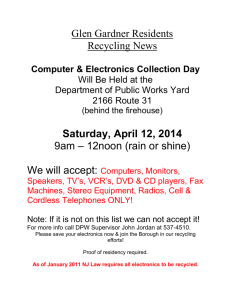

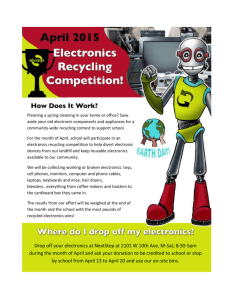

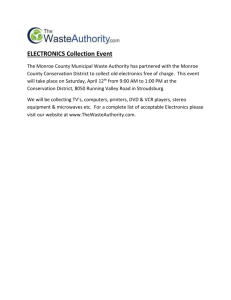

advertisement