Full Article (PDF file) - Journal of Gastrointestinal and

advertisement

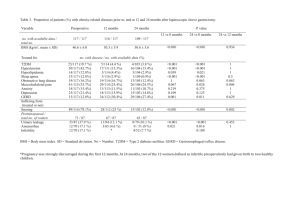

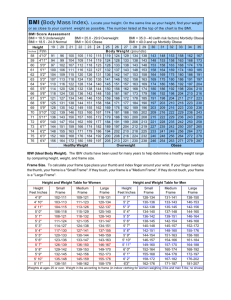

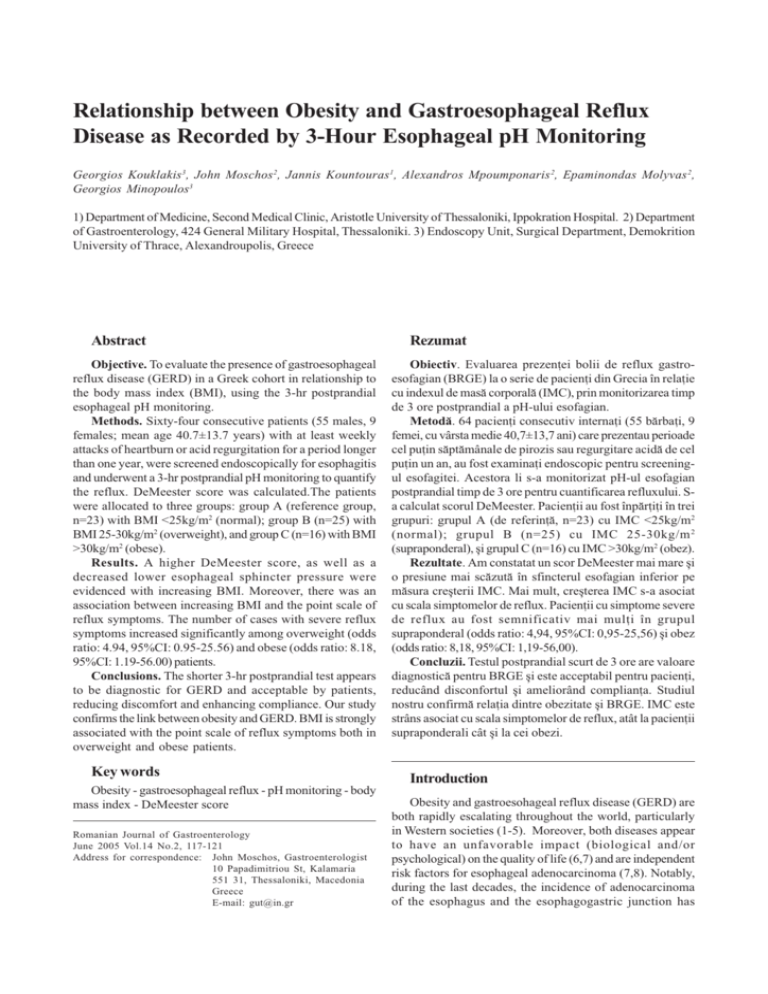

Obesity impact on GERD Relationship between Obesity and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease as Recorded by 3-Hour Esophageal pH Monitoring Georgios Kouklakis3, John Moschos2, Jannis Kountouras1, Alexandros Mpoumponaris 2, Epaminondas Molyvas 2, Georgios Minopoulos3 1) Department of Medicine, Second Medical Clinic, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Ippokration Hospital. 2) Department of Gastroenterology, 424 General Military Hospital, Thessaloniki. 3) Endoscopy Unit, Surgical Department, Demokrition University of Thrace, Alexandroupolis, Greece Abstract Objective. To evaluate the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in a Greek cohort in relationship to the body mass index (BMI), using the 3-hr postprandial esophageal pH monitoring. Methods. Sixty-four consecutive patients (55 males, 9 females; mean age 40.7±13.7 years) with at least weekly attacks of heartburn or acid regurgitation for a period longer than one year, were screened endoscopically for esophagitis and underwent a 3-hr postprandial pH monitoring to quantify the reflux. DeMeester score was calculated.The patients were allocated to three groups: group A (reference group, n=23) with BMI <25kg/m2 (normal); group B (n=25) with BMI 25-30kg/m2 (overweight), and group C (n=16) with BMI >30kg/m2 (obese). Results. A higher DeMeester score, as well as a decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure were evidenced with increasing BMI. Moreover, there was an association between increasing BMI and the point scale of reflux symptoms. The number of cases with severe reflux symptoms increased significantly among overweight (odds ratio: 4.94, 95%CI: 0.95-25.56) and obese (odds ratio: 8.18, 95%CI: 1.19-56.00) patients. Conclusions. The shorter 3-hr postprandial test appears to be diagnostic for GERD and acceptable by patients, reducing discomfort and enhancing compliance. Our study confirms the link between obesity and GERD. BMI is strongly associated with the point scale of reflux symptoms both in overweight and obese patients. Key words Obesity - gastroesophageal reflux - pH monitoring - body mass index - DeMeester score Romanian Journal of Gastroenterology June 2005 Vol.14 No.2, 117-121 Address for correspondence: John Moschos, Gastroenterologist 10 Papadimitriou St, Kalamaria 551 31, Thessaloniki, Macedonia Greece E-mail: gut@in.gr Rezumat Obiectiv. Evaluarea prezenþei bolii de reflux gastroesofagian (BRGE) la o serie de pacienþi din Grecia în relaþie cu indexul de masã corporalã (IMC), prin monitorizarea timp de 3 ore postprandial a pH-ului esofagian. Metodã. 64 pacienþi consecutiv internaþi (55 bãrbaþi, 9 femei, cu vârsta medie 40,7±13,7 ani) care prezentau perioade cel puþin sãptãmânale de pirozis sau regurgitare acidã de cel puþin un an, au fost examinaþi endoscopic pentru screeningul esofagitei. Acestora li s-a monitorizat pH-ul esofagian postprandial timp de 3 ore pentru cuantificarea refluxului. Sa calculat scorul DeMeester. Pacienþii au fost înpãrþiþi în trei grupuri: grupul A (de referinþã, n=23) cu IMC <25kg/m2 (normal); grupul B (n=25) cu IMC 25-30kg/m 2 (supraponderal), ºi grupul C (n=16) cu IMC >30kg/m2 (obez). Rezultate. Am constatat un scor DeMeester mai mare ºi o presiune mai scãzutã în sfincterul esofagian inferior pe mãsura creºterii IMC. Mai mult, creºterea IMC s-a asociat cu scala simptomelor de reflux. Pacienþii cu simptome severe de reflux au fost semnificativ mai mulþi în grupul supraponderal (odds ratio: 4,94, 95%CI: 0,95-25,56) ºi obez (odds ratio: 8,18, 95%CI: 1,19-56,00). Concluzii. Testul postprandial scurt de 3 ore are valoare diagnosticã pentru BRGE ºi este acceptabil pentru pacienþi, reducând disconfortul ºi ameliorând complianþa. Studiul nostru confirmã relaþia dintre obezitate ºi BRGE. IMC este strâns asociat cu scala simptomelor de reflux, atât la pacienþii supraponderali cât ºi la cei obezi. Introduction Obesity and gastroesohageal reflux disease (GERD) are both rapidly escalating throughout the world, particularly in Western societies (1-5). Moreover, both diseases appear to have an unfavorable impact (biological and/or psychological) on the quality of life (6,7) and are independent risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma (7,8). Notably, during the last decades, the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and the esophagogastric junction has 118 increased fivefold in Europe and the United States (9,10). Although there is a general belief that obese people are more likely to develop GERD, scientific evidence suggesting that obesity plays a causal role in this disease is limited and inconsistent (7,8). The history of the most common symptoms of GERD (heartburn, acid regurgitation, and some degree of dysphagia) is usually sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of GERD and to permit proper treatment (11). In addition, ambulatory 24-hour (hr) esophageal pH monitoring is the most commonly used test for establishing the existence of excessive GERD, for correlating symptoms temporally with reflux and for quantifying esophageal acid exposure (11). However, a limitation of the long-lasting 24-hr pH monitoring is that it represents an uncomfortable experience (12), thereby leading to low acceptance of this test by patients. Moreover, patients do not constantly keep the probe in for 24 hours (13). Therefore, a shorter trial may be more tolerable to the patients. In this study, we have introduced the 3-hr postprandial esophageal pH monitoring as a more flexible and tolerable test to evaluate the presence of GERD in a Greek cohort of patients, presenting the classical symptoms of reflux disease, in relationship to their body mass. Patients and methods Sixty-four consecutive patients (55 males and 9 females; mean age 40.7±13.7 years) with at least weekly attacks of heartburn or acid regurgitation for a period no less than one year, were screened for the presence of endoscopic findings of esophagitis and the performance of 3-hr postprandial pH monitoring study to quantify the reflux. Since heartburn and acid regurgitation are the chief symptoms of GERD, participants answered a question if symptoms were mild, moderate or severe. In particular, heartburn was evaluated using a 4-point scale: none (no heartburn), mild (awareness of heartburn, but easily tolerated), moderate (discomforting heartburn sufficient to cause interference with normal activities including sleep) and severe (incapacitating heartburn, with inability to perform normal activities including sleep). All participants underwent certain physical examinations, including assessment of body weight, height, and body mass index (BMI; weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters). The patients were then allocated in three groups, according to predetermined BMI cut-off points of the World Health Organization classification of overweight and obesity. In this regard, group A (reference group) consisted of 23 patients (19 males, 4 females; mean age 40.1±18.0 years) with BMI <25 kg/m2 (normal); group B included 25 patients (22 males, 3 females; mean age 40.4±10.6 years) with BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2 (overweight), and group C consisted of 16 patients (15 males, 1 female; mean age 40.5±11.5 years) with BMI >30 kg/m2 (obese). Among the obese patients, there were 4 severely obese cases (BMI >35 kg/m2). Kouklakis et al Exclusion criteria included a past history of gastric or esophageal surgery (apart from cholecystectomy), malignant disease, esophageal ring stricture or esophagitis secondary to systemic events (e.g. scleroderma or ingested irritants), primary esophageal motility disorders and age <18 years (13,14). Patients with endoscopic evidence of active gastrointestinal bleeding, those with Zollinger-Ellisons syndrome, women who were pregnant or lactating, and those with any condition likely to result in poor compliance were also excluded from the study. All patients had stopped acid suppression therapy (four days beforehand for those taking antacids, or one month beforehand for those using H2receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors), and underwent a four-week wash-out period during which any medications that affect motility, including tricyclic antidepressants and laxatives, were tapered. None of the patients received oral medications that could cause reflux disease symptoms (e.g., alendronate sodium, nifedipine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). After having given informed consent, all 64 patients underwent elective diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to assess the severity of reflux esophagitis according to the Los Angeles classification (15). Study design The subjects reported at 9 a.m. after a 12-hr fast. Intravenous sedation was given, and a routine upper endoscopic examination (Fujinon EPX-201 endoscope system; Fujinon Optical, Tokyo, Japan) was carried out to identify evidence of macroscopic abnormalities. Endoscopes were sterilized between procedures according to standard guidelines (16). After an overnight fast, esophageal manometry was performed using a 4-channel, silicone rubber, low compliance, pneumohydraulic, perfused manometric assembly (model PIP-4-8SS, Mui Scientific, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The manometric assembly was passed transnasally and the position of the lower esophageal sphincter was determined using the station pull-through technique on 0.5 cm intervals. After removal of the manometric catheter, a monocrystalline antimony pH catheter was passed transnasally and the electrode was positioned 5 cm above the manometrically determined upper margin of the lower esophageal sphincter. The electrode was calibrated in buffering solutions of pH 4 and pH 7 before each study. Three-hr postprandial ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring was then carried out. Patients were instructed to mark the event recorder with regard to meal and recumbency and to work according to their daily routine except that coffee, alcohol, fruit juices and antacids had to be avoid (17). Data acquisition was performed using a portable data logger (pHmetry UPS-2020, Medical Measurement Systems b.v., Enschede, The Netherlands). Semi-automated analysis was performed with the aid of commercially available software. Reflux episode was defined as esophageal pH<4 in the distal esophagus. Parameters of esophageal acid Obesity impact on GERD 119 exposure included the standard DeMeester score. All analyses were performed by a single investigator (JM). For comparisons of the age (years) among the three groups of patients, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used and there was no significant difference between the groups. Comparisons of mean values of DeMeester score and mean values of lower esophageal sphincter pressure among the three study groups were made by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Finally, concerning the gastroesophageal reflux symptomatology and the endoscopical findings, the odds ratios of groups B and C versus reference group A were calculated. P value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. There was an association between increasing BMI and the point scale of reflux symptoms (Table I). Compared with those with BMI less than 25, the cases with severe reflux symptoms increased significantly among the overweight (odds ratio: 4.94, 95%CI: 0.95-25.56) and obese patients (odds ratio: 8.18, 95%CI: 1.19-56.00). When compared with the reference group, there was also a propensity of increasing severity of endoscopic appearing esophagitis, according to the Los Angeles classification system, in overweight and obese patients (Table II). Discussion There is conflicting evidence that obesity per se predisposes to GERD. Although some large cross-sectional population-based studies examining the relationship between body mass and GERD found that BMI was strongly positively related to the frequency of symptoms of GERD (18-21) others showed disbelief in such an association, suggesting that gastro-esophageal reflux symptoms occur independently of BMI and weight reduction may not be justifiable as an antireflux therapy (22). Our study confirms the link between obesity (defined as BMI >30 kg/m2) and reflux symptoms, showing that BMI is strongly associated with the point scale of reflux symptoms both in overweight and obese patients compared with those with normal BMI. We strictly used the main symptoms, heartburn and regurgitation, which are considered to be the most useful for the diagnosis of GERD. These symptoms occurred at least once a week, indicating the good validity of reflux symptom data and the fact that our selected subjects were representative of the population at large. However, a limitation of our study was the small number of women (n=9 in all 3 categories of BMI), thereby not allowing for comparisons between the two sexes. On the other hand, Results Group A (reference group) patients had a mean BMI 23.4 ±1.4 kg/m2 and their mean DeMeester score was 27.8 ±20.7. Group B (overweight) patients had a mean BMI 27.4 ±1.0 kg/m2 and a mean DeMeester score 39.1 ±42.1. Group C (obese) patients had a mean BMI 32.6 ±3.2 kg/m2 and a mean DeMeester score 62.5 ±45.3. A significantly higher DeMeester score (F-ratio: 4.24, P=0.019) was evidenced as the BMI increased. All subjects found it tolerable to wear the probe for 3-hr postprandial analysis, and kept the probe in for the shorter 3-hr test. Group A (reference group) patients had a mean BMI 23.4 ±1.4 kg/m2 and their mean lower esophageal sphincter pressure was 16.04 ± 2.117. Group B (overweight) patients had a mean BMI 27.4 ±1.0 kg/m2 and their mean lower esophageal sphincter pressure was 14.08 ± 2.361. Group C (obese) patients had a mean BMI 32.6 ±3.2 kg/m2 and their mean lower esophageal sphincter pressure was 10.94±2.175. A significantly decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure (F-ratio: 26.827, P<0.001) was evidenced as the BMI increased. Table I Comparison of gastroesophageal reflux symptomatology of groups B and C versus reference group A; ellipses indicate not applicable No Mild Moderate Severe Group A n=23 Group B n=25 Group C n=16 Odds ratio B vs. A (95% CI) Odds ratio C vs. A (95% CI) 0 (0%) 16 (69.6%) 5 (21.7%) 2 (8.7%) 1 8 8 8 0 4 5 7 0.21 (0.06-0.70) 1.70 (0.47-6.19) 4.94 (0.95-25.56) 0.15 (0.04-0.60) 1.64 (0.37-7.19) 8.18 (1.19-56.00) (4%) (32%) (32%) (32%) (0%) (25%) (31.2%) (43.8%) Table II Comparison of endoscopical findings of groups B and C versus reference group A; ellipses indicate not applicable Normal Esophagitis A Esophagitis B Esophagitis C Barretts esophagus Hiatal hernia Group A n=23 Group B n=25 Group C n=16 Odds ratio B vs. A (95% CI) Odds ratio C vs. A (95% CI) 11 (47.8%) 7 (30.4%) 4 (17.4%) 0 (0%) 1 (4.3%) 9 (39.1%) 10 (40%) 7 (28%) 7 (28%) 1 (4%) 0 (0%) 14 (56%) 4 2 6 2 2 7 0.73 0.89 1.85 1.98 0.36 0.33 2.85 3.18 1.21 (25%) (12.5%) (37.5%) (12.5%) (12.5%) (43.8%) (0.23-2.29) (0.26-3.10) (0.47-7.32) (0.63-6.26) (0.09-1.42) (0.06-1.67) (0.61-13.34) (0.21-47.94) (0.33-4.45) 120 Nilsson et al, who found a significant association between body mass and reflux esophagitis in female in contrast to male patients, hypothesized that this might be caused by increased estrogen activity in overweight and obese females (19), thereby suggesting that estrogens may play an important role in the etiology of reflux disease (8). If the latter hypothesis is correct, then our findings might be of more value, as our cohort consisted mainly of male patients. The causation between the BMI and reflux symptoms is still not clearly known but factors such as increased sensitivity of the esophagus to acid, increased intraabdominal pressure, and vagal abnormalities in obese patients may cause higher bile and pancreatic enzyme output, thus making the resulting refluxate more toxic (23). In our study, we implemented strict exclusion criteria involving any obvious causes other than the BMI that might have been responsible for the reflux symptoms. Furthermore, although it has been postulated that the presence of hiatus hernia and a higher BMI are associated with the development of reflux esophagitis (24,25), such a finding was not observed in our cohort. Indeed, hiatal hernia incidence was about the same in all three categories of BMI. From another viewpoint, body composition affects the pharmacokinetics of drugs administered for GERD. Although there are few data about the efficacy of drug treatments in obese patients, poor absorption or a larger distribution of body mass may lead to the medications being less effective in their action. Subsequently, less effective treatment can lead to further complications in the long term (26). However, larger distribution of body mass was observed only in a minority of our patients (4 severely obese cases), and all the patients in our study had stopped acid suppression therapy that would have altered our results and had not received any oral medications that could cause reflux disease symptoms. The association between BMI and endoscopically verified case subjects with reflux esophagitis is also ambiguous. Some population-based case-control endoscopical studies found a strong and dose-dependent association between body mass and reflux esophagitis (24), particularly in women rather than among men (19), while other studies found that massive overweight is not associated with an increased prevalence of GERD (27). Our results seem to be in accordance with the first studies; a propensity of increasing severity of endoscopic appearing esophagitis (according to the LA classification) and Barretts esophagus was observed in the overweight and obese subjects of our study. However, due to the small number of cases included in our study, large-scale studies are needed to draw definite conclusions. There are few published studies on the use of the ambulatory 24-hr pH monitoring to investigate the prevalence of GERD with regard to BMI, reporting a more or less strong correlation between BMI and severity of gastroesophageal reflux (28-30). Although the ambulatory pH study is currently the best test available that identifies the presence of GERD in a physiological manner, our Kouklakis et al previous experience in using this method on Greek patients yielded uncomfortable experiences, also reported by others (12), leading to a very low acceptance of this test by our patients. Therefore, we decided to introduce the 3-hr postprandial esophageal pH monitoring as a more flexible and tolerable test to evaluate the presence of GERD in relationship with their body mass. We believe this is not a disadvantage because, according to previously published data, the sensitivity and specificity of a 3-hr postprandial test were found to be 88% and 98%, respectively, compared with the 24-hr pH study for the assessment of GERD (13). In our study, reflux was defined and quantified using the DeMeester score (30). The shorter 3-hr postprandial test appears to be diagnostic for GERD and acceptable by patients, reducing discomfort and enhancing compliance. However, larger prospective evaluations of this test are needed to draw more definite conclusions. Our results indicate that there was a strong correlation between BMI and the severity of gastroesophageal reflux. Indeed, patients who were overweight and obese had significantly higher distal esophageal acid exposure time and so a higher DeMeester score. It can be assumed that the barrier to gastroesophageal reflux is rendered insufficient in patients who are overweight (30). We found that a significantly decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure was evidenced as the BMI increased. Another possible mechanism could be that in obese subjects, cholecystokininstimulated pancreatic enzyme secretion, emptying of bile acids and gastrin release are reduced compared with patients with normal BMI. Notably, the changes in the pancreatic and gallbladder function found in obesity may alter the composition of the refluxate, thus rendering it more toxic to the esophageal mucosa (31). Future larger cohort studies are needed to elucidate these mechanisms. References 1. Rami B, Schober E, Kirchengast S, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in male adolescents in Austria between 1985 and 2000. A population based study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2004;17:67-72. 2. Lindstrom M, Isacsson SO, Merlo J. Increasing prevalence of overweight, obesity and physical inactivity: two populationbased studies 1986 and 1994. Eur J Public Health 2003;13:306312. 3. Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Campbell SM, et al. Increasing prevalence of overweight among US adults. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1960 to 1991. JAMA 1994;272:205-211. 4. Lim LG, Ho KY. Gastroesophageal reflux disease at the turn of millennium. World J Gastroenterol 2003;9:2135-136. 5. Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, et al. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:1448-1456. 6. Eloubeidi MA, Provenzale D. Health-related quality of life and severity of symptoms in patients with Barretts esophagus and gastroesophageal reflux disease patients without Barretts esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1881-1887. Obesity impact on GERD 7. Denke MA. Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity. In: Sleisenger and Fordtrans Gastrointestinal and liver disease. 7th edn, Saunders, Philadelphia 2002, 310-336. 8. Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, et al. Obesity and estrogen as risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. JAMA 2003; 290:66-72. 9. Walther C, Zilling T, Perfekt R, et al. Strongly increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric Cardia [Swedish]. Lakartidningen 2004;101:180-183. 10. Ginsberg GG, Fleischer DE. Esophageal tumors. In: Sleisenger and Fordtrans Gastrointestinal and liver disease. 7th edn, Saunders, Philadelphia 2002, 647-671. 11. Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications, including Barretts metaplasia. In: Sleisenger and Fordtrans Gastrointestinal and liver disease. 7th edn, Saunders, Philadelphia 2002, 599-622. 12. Sarani B, Gleiber M, Evans SR. Esophageal pH monitoring, indications, and methods. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002;34:200206. 13. Arora AS, Murray JA. Streamlining 24-hour pH study for GERD: Use of a 3-hour postprandial test. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:1015. 14. Birbara C, Breiter J, Perdomo C, et al. Rabeprazole for the prevention of recurrent erosive or ulcerative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Rabeprazole Study Group. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;12:889-897. 15. Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999;45:172180. 16. [No authors listed]. Cleaning and disinfection of equipment for gastrointestinal flexible endoscopy: interim recommendations of a Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 1988;29:1134-1151. 17. Wu JC, Chan FK, Wong SK, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on oesophageal acid exposure in patients with reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16:545-552. 18. Murray L, Johnston B, Lane A, et al. Relationship between body mass and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: The Bristol Helicobacter Project. Int J Epidemiol 2003; 32:645650. 121 19. Nilsson M, Lundegardh G, Carling L, et al. Body mass and reflux oesophagitis: an oestrogen dependent association? Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:626-630. 20. Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, et al. Risk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med 1999;106:642-649. 21. Fraser-Moodie CA, Norton B, Gornall C, et al. Weight loss has an independent beneficial effect on symptoms of gastrooesophageal reflux in patients who are overweight. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34:337-340. 22. Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. No relation between body mass and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in a Swedish population based study. Gut 2000; 47:26-29. 23. Barak N, Ehrenpreis ED, Harrison JR, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in obesity: pathophysiological and therapeutic considerations. Obesity Rev 2002;3:9-15. 24. Stene-Larsen G, Weberg R, Froyshov Larsen I, et al. Relationship of overweight to hiatus hernia and reflux oesophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol 1988;23:427-432. 25. Lee SJ, Song CW, Jeen YT, et al. Prevalence of endoscopic reflux esophagitis among Koreans. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;16:373-376. 26. Dixon A, Jankowski J. The relation of obesity, reflux and its implications. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:650-651. 27. Lundell L, Ruth M, Sandberg N, et al. Does massive obesity promote abnormal gastroesophageal reflux? Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:1632-1635. 28. Mathus-Vliegen EM, Tygat GN. Gastro-oesophageal reflux in obese subjects: influence of overweight, weight loss and chronic gastric balloon distension. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:12461252. 29. Mathus-Vliegen LM, Tytgat GN. Twenty-four-hour pH measurements in morbid obesity: effects of massive overweight, weight loss and gastric distension. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996;8:635-640. 30. Wajed SA, Streets CG, Bremner CG, et al. Elevated body mass disrupts the barrier to gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Surg 2001;136:1014-1018. Discussion 1018-1019. 31. Wisen O, Rossner S, Johansson C. Impaired pancreatico-biliary response to vagal stimulation and to cholecystokinin in human obesity. Metabolism 1988;37:436-441.