1 PART I. INTRODUCTION 1. Rationale of the study In the

advertisement

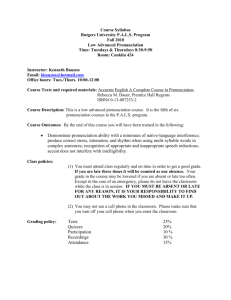

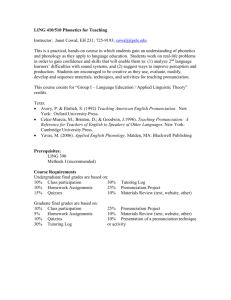

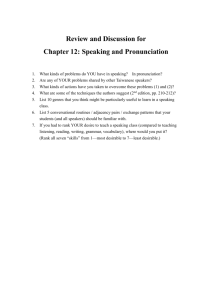

1 PART I. INTRODUCTION 1. Rationale of the study In the last decades, the general goals of teaching have primed the effective use of the spoken language to establish successful communication. That is why there has been a steady growth in the attention to the magnitude of speaking and pronunciation teaching. This fact has brought about an emergent debate about models, goals and particularly, the methodology used for speaking and pronunciation teaching. A number of research studies have dealt with pronunciation teaching and problems students face in English pronunciation. The research findings have revealed that pronunciation frequently interferes with communication. As a matter of fact, communication may break down when people pronounce incorrectly. Moreover, learners with good pronunciation are usually more proficient speakers and more successful language learners than those with poor pronunciation. Since I started teaching at Hong Duc University, I have taught speaking and pronunciation to first-year English majors many times. I have always been trying my best to help my students pronounce better. However, I have had many frustrations because my students always have many mistakes in their pronunciation. I have been investigating into the reasons for this, and I have found that my students, most of whom are from rural areas in the province, only learned grammar and never focused on pronunciation at secondary school. Moreover, they did not have much access to native speakers’ pronunciation. For non-English majors at other departments of Hong Duc University, they are required to have intelligible pronunciation. English majors at Foreign Department, however, must go far beyond the intelligibility to the point that they should sound like or nearly like native speakers because they will become teachers of English and their pronunciation will affect many generations to come. That is the reason why first-year English majors’ weak pronunciation has been a matter of serious concern among us. 2 Due to the importance of pronunciation in language learning and the poor pronunciation of first-year English majors at Hong Duc university, I decided to introduce some changes into my speaking and pronunciation course for first-year English majors with the hope to improve their pronunciation. That was the reason why I conducted this study “Using software to improve first-year English majors’ pronunciation: An action research at Hong Duc University”, which tried to exploit the software programs available in my speaking and pronunciation lessons with an aim to improve first-year English majors’ pronunciation. 2. Purposes of the study The purpose of this study is to improve English pronunciation for first-year English majors at Hong Duc University. Specifically, it has three purposes as follows: - To identify students’ most common mistakes in their English pronunciation. - To exploit the software program, namely Pronunciation Power as an intervention in pronunciation lessons to improve students’ pronunciation. - To justify the effectiveness of using pronunciation software in teaching English pronunciation to first-year English majors. 3. Research questions Regarding the importance of pronunciation teaching, purpose of the research and statement of the problem, this study is accomplished to find the answer to the question ‘How effectively is software exploited to improve first-year English majors’ pronunciation at Hong Duc university?’. Specifically, the study addressed the following three research questions: * What are the students’ most common problems regarding their English pronunciation? * Is Pronunciation Power effective in teaching first-year English majors’ pronunciation? * If yes, how effective is it? 3 4. Scope of the study The study concentrates on improving first-year English majors at Hong Duc University by using the pronunciation software named Pronunciation Power. Within its scope, the research was aimed at justifying the effectiveness of using this software program in teaching English pronunciation to first-year English majors at Hong Duc university. 5. Methods of the study This study is conducted as an action research because it is aimed at improving first-year English majors’ pronunciation. In order to get data, a combination of different instruments, namely class observation, informal interviews and audio-recording, is used. The data collected from the observation and interviews will be analyzed by qualitative method, and the data collected through the tape scripts will be analyzed by quantitative method. 6. Significance of the study Even though there have been numerous studies on pronunciation teaching, few investigations into the use of software in teaching pronunciation are conducted. This research provides an insight into the effectiveness of applying pronunciation software to the teaching of pronunciation to first-year English majors. The results of the study will, therefore, be much beneficial to both teachers who are considering whether to exploit software programs in their English pronunciation lessons and students who are interested in using software programs to improve their English pronunciation. 7. Design of the study The study consists of three main parts as follows. The first part deals with rationale, purposes, research questions, scope, methods and design of the study. 4 The second part contains three chapters, in which chapter 1 reviews the literature focusing on the theoretical basis related to teaching pronunciation and using CALL programs in language learning and teaching, chapter 2 presents a detailed description of the research methodology, and chapter 3 discusses the findings of the study. The final part summarizes all the main ideas expressed throughout the research, provides pedagogical implications and suggests further research orientations. 5 PART II. DEVELOPMENT CHAPTER 1. LITERATURE REVIEW 1.1. Role of pronunciation in language learning According to Levis and Grant (2002: 13), most language teachers agree that “Intelligible pronunciation is vital to successful communication” and most students see “pronunciation as an important part of learning to speak...” Sifakis and Sougari (2005) states that pronunciation is crucial to language learning because of two reasons. First, it helps make communication in a certain setting among NNSs or between NNSs and NSs possible. This is performed by speakers’ use of intelligible sounds and prosodic features together with other aspects of language such as grammar, discourse, dialect and so forth. Second, pronunciation contributes to the establishment of their socio-cultural identity (pp.469 – 470). Kelly (2000: 11) also believes that it is vital for a language learner to have a good pronunciation of that language. Learners may have acquired a considerable amount of grammar and vocabulary, but still fail to communicate effectively due to their poor pronunciation. Pronunciation plays a vital role in learners’ speaking ability. Only when a learner is competent in pronunciation can his speaking skills be acclaimed. Kelly continues to emphasize that mispronunciation of sounds and misuse of prosodic features are responsible for the listeners’ failure to be comprehended and to interpret what the speaker means, which leads to the disappointment of the speaker. Furthermore, Stevick (1978) justifies that pronunciation is a primary medium for communication of information through which we bring our use of language to the attention of other people and the teaching of pronunciation should therefore be given priority in a language class. 6 According to Murphy (1991), given that most courses emphasize general oral communication over pronunciation, teachers must seek creative ways to integrate pronunciation into speakingoriented classes in a manner clearly related to the oral communication goals of the course. He also adds that pronunciation instruction needs to be integrated with broader level communicative activities in which speakers and listeners engage in meaning communication. It is obvious in my situation as a teacher of English that students’ weak pronunciation has negative effect on their ability to express themselves and their ability to listen to others, especially to native speakers. Speakers with wrong pronunciation find it difficult to make themselves understood by the teacher and other students, which makes them embarrassed and hesitant to continue speaking. Moreover, when a learner has already stuck to the wrong way of pronouncing a particular word, phrase or sentence, (s)he is unlikely to recognize the authentic pronunciation by a native speaker and fail to interpret what the speaker means. Therefore, it can be concluded that pronunciation play an essential role in learning a foreign language because it is intelligible pronunciation that make communication possible and even if a speaker uses the right words with the right structure but without correct or intelligible pronunciation, s(he) is likely to cause misunderstanding, communication interruption, or even communication breakdown. 1.2. Aspects of pronunciation teaching As regards what teaching pronunciation involves, Ur (1996:47) claims that “the concept of “pronunciation” may be said to include: - the sounds of the language, or phonology, - stress and rhythm - intonation.” Martin Hewings in his book Pronunciation Practice Activities presents that the following elements should be included in the English pronunciation teaching: 7 - Segmental features with more focus on consonants, consonant clusters and vowel length - Suprasegmental features consisting of word stress, tonic words, weak and strong forms, connected speech and tone. (pp.15 – 16) 1.2.1. Vowel sounds Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., and Goodwn, J. (1996) defines vowels as “sounds in which there is continual vibration of the vocal cords and the air stream is allowed to escape from the mouth in an obstructed manner, without any interruption.” According to Roach (1998), vowels are “sounds in the production of which there is no obstruction to the flow of air as it passes the larynx to the lips.” Vowels can be classified in terms of: - the height of the bulk of the tongue in the mouth. - the front/back position of the tongue in the mouth.- the degree of lip-rounding. - the length of vowels. The classification can be shown in the following diagram: Diagram 1. English vowels 8 1.2.2. Consonant sounds According to Kelly. G, (2003:24), “consonants are formed by interrupting, restricting or diverting the airflow in a variety of ways.” Roach (1998) define consonants as “sounds in which there is obstruction to the flow of air as it passes the larynx to the lips.” Consonants are classified according to: - the manner of articulation - the place of articulation - the force of articulation The classification of English consonants can be shown in the following table: Table 1. English consonants 9 1.2.3. Word stress Avery and Ehrlich’s (1992) state that word stress involves making vowels longer and louder. Randolph Quirk and Sidney Greenbaun (1973:450) defines stress as the prominence with which one part of a word or of a longer utterance is distinguished from other parts. According to Pennington, stress has at least three prosodic features, which are duration (or length), intensity (or loudness) and pitch (or fundamental frequency). Word stress is closely related to intelligibility because when a word is said with incorrect stress pattern, the listener may spend time searching for the word in the wrong stress category. A stress pattern mistake can, therefore, cause a great deal of confusion. That is the reason why Kelly (2000) emphasizes that it would be practical to base our teaching principle on a twolevel division (stressed or unstressed). 1.2.4. Sentence stress According to Avery and Ehrlich (1992), in a particular sentence, one content word receives greater stress than all others, which is referred as the major sentence stress. In most cases, the major sentence stress falls on the last content word within a sentence. However, there are also cases in which the major sentence stress will not fall on the final content word of the sentence. It depends on the speakers who decide which word in their speech they want to give more or less prominence. A word may be given less weight because it has been said already, or it may be given more weight because the speaker want to highlight it. The use of incorrect stress in English can make it difficult for listeners to identify the meaning of the sentence. Kenworthy (1987) demonstrates that there is a great deal of evidence that native speakers rely very much on the stress pattern of words when they are listening, and that when a native speaker mishears a word, it is because the foreigner has put the stress in the wrong place, not because he or she mispronounced the sounds of the word. 10 1.2.5. Rhythm Kenworthy (1987:30) claims that rhythm is a product of word stress and the way in which important items are foregrounded through their occurrence on a strong beat, and unimportant items are backgrounded by their occurrence on a weak beat. Dalton and Seidlhofer (1994) also give the similar description of rhythm concentrating on the contrast between stress and unstress, which states that “utterances are continuous strings of syllables, the stressed syllables provides the foreground and the unstressed ones the backgrounds.” English has a stress-timed rhythm, in which stressed syllables recur at equal intervals of time but unstressed syllables are unequally spaced in time. The amount of time it takes to say a sentence depends on the number of syllables that receive stress, not on the total number of syllables. This should be distinguished from syllable-timed rhythm like Vietnamese, in which all the syllables recur at equal intervals of time, stressed or unstressed, so that Vietnamese students can avoid the interference of their mother tongue in the target language. 1.2.6. Intonation According to Kelly (2000), intonation refers to the way the voice goes up and down in pitch when we are speaking. He also claims that “it is a fundamental part of the way we express our own thoughts and it enables us to understand those of others.” Four basic tunes of English are as follows: - The falling tune (the glide-down) - The first rising tune (the glide-up) - The second rising tune (the take-off) - The falling-rising tune. Intonation has the function as the expression of speaker’s attitude and purpose in saying something such as greeting you, telling you something, asking you, ordering you, pleading 11 with you or thanking you etc… Intonation is therefore important for intelligibility. Inappropriate intonation pattern can lead to misunderstanding just as mispronounced sound can. The importance of raising students’ awareness of the uses of four basic tunes of English in order to improve their communicative performance is therefore can not be denied. 1.2.7. Other aspects of connected speech The following aspects appear when English is spoken in casual and rapid everyday speech. * Assimilation According to Kelly (2000), assimilation is the modification of sounds on each other when they meet, usually across word boundaries, but can also within words. Assimilation is said to be progressive when a sound influences a following sound, or regressive when a sound influences one which precedes it. * Word linking When a word finishes with a consonant and is followed by another word which an initial vowel, the final consonant of the first word will join with the first vowel of the second one. * Elision Kelly (2000) define elision as “the disappearance of a sound. In saying an utterance, some sounds are deleted due to the fast speed and also due to the economy of effort, when people do not want to try hard in pronouncing every single sound. 1.3. Approaches to pronunciation teaching 1.3.1. Explicit or Implicit In a summary of the application of explicit phonetic instruction in pronunciation teaching, Derwing and Munrol (2005:388) explain explicit phonetic instruction as follows: "Just as students learning certain grammar points benefit from being explicitly instructed to notice the 12 difference between their productions and those of L1 speakers, so students learning L2 pronunciation benefit from being explicitly taught phonological form to help them notice the difference" In a well-known study by Derwing, Munrol and Wiebe (1998), explicit instruction was given to the experimental group and not to the control group. Both groups were evaluated before and after the experiment by both trained and untrained listeners. The results demonstrated that explicit phonetic instruction enhanced learners' pronunciation of the target language. Luchini in his article “Task-Based Pronunciation Teaching: A State-of-the-art Perspective” argues that “…the formal instruction of those common core features of English pronunciation – vowel length, nuclear stress (especially contrastive stress), and voice setting – which seem to be vital for establishing intelligibility enable learners to take utmost advantage of both their receptive and productive pronunciation skills.” (p.197) However, not all researchers agree that formal and explicit instruction can help students to improve their pronunciation. Roach,1983; Dalton and Seihofer, 1994; among others state that numerous students can not gain all the prosodic features when they are overly taught, which can only be implicitly learnt by long-term exposure to the target language. (p195) I myself believe that overt instruction is necessary in the speaking and pronunciation lessons, especially for my first-year English major students at Hong Duc university because they will become teachers of English and they need to know exactly how a sound, a word, a phrase, an utterance or a sentence is pronounced, so that they can teach their pupils in the forthcoming future, not just to learn pronunciation implicitly without thorough understanding of it. However, this does not mean that implicit learning is not important. Teachers should on the one hand give explicit phonetic instructions and on the other hand encourage students to continuously expose to the target language. 13 1.3.2. Top-down or Bottom-up Pronunciation teaching consists of 2 parts: segmental (consonants, vowels and clustering) and suprasegmental (thoughts group, prominence, intonation and syllable structure). Dalton & Seidhofer in their book Pronunciation identify two approaches to pronunciation teaching including bottom-up and top-down. In bottom-up approach, the segmental features are to be taught first, then the suprasegmentals will naturally be gained. Whereas, in the top-down approach, the prosodic features are to be learnt before the segments. (pp.69-70) According to Celce-Murcia (2001), the top-down approach, in which suprasegmental aspects of pronunciation are addressed first, has been the main trend in pronunciation teaching. Field (2005:20) also states that suprasegmentals should be taught first in order to improve learners’ intelligibility. He explains that the results of numerous research have shown the importance of suprasegmentals over the segmentals. Moreover, segmentals are manageable because listeners can use their lexical knowledge to interpret the phonemes In contrast to Celce-Murcia and Field, Levis (2005) claims that the mainstream emphasis on suprasegmental aspects is not entirely valid because it is not based on sound research and he points out a segmental focus makes a more important contribution to intelligibility. Saito (2007:20) also emphasizes the importance of teaching segmental prior to suprasegmental features and argues that the communication can get through if the speakers use the wrong prosody because the listeners can interpret what the speakers mean, but the speakers’ mispronunciation of the sounds in minimal pairs can lead to communication disruption. Luchini (2005:195), however, balances these two approaches when he assumes that we should equilibrate between segmentals and suprasegmentals so that students can decide whether they desire to be native-like speakers or not. He goes on to argue that both segmental and suprasegmental features are important in making one’s pronunciation intelligible. In the researcher’s intervention, she followed the bottom-up approach in which segmental features were taught before suprasegmental ones. 14 1.4. Computers-assisted language learning (CALL) and EFL learning and teaching During the last decades, much CALL research has explored the potential of technology as well as multimedia—the combination of text, audio, video, graphics, and animations—as a tool to teach and reinforce English language learning. These studies focus on justifying the effectiveness of the application of certain technologies in specific language skill areas. In his recent literature review and meta-analysis, Zhao (2003) identifies three problems with assessing the effectiveness of technology. First is the problem of defining what counts as technology (videos, CALL tutorials, and chat rooms, for example, are obviously very different). The second problem is separating a technology from its particular uses. Because any given technology may be used in a variety of ways, some effective, some not, it is difficult to generalize about the effectiveness of a technology itself. The third issue has to do with the effects of other mediating factors, such as the learners, the setting, the task(s), and the type of assessment. Zhao attempted to address these issues by performing a meta-analysis of stringently selected studies published between 1997 and 2001. Including technologies ranging from video to speech recognition to web tutorials, Zhao found a significant main effect for technology applications on student learning. According to (Wood, 2001) and Nikolova (2002), multimedia is seen as supporting vocabulary acquisition because it can effectively present new lexical items and enable learners to practice them with visual referents and through gaming formats that include visual and auditory information, which improve retention. Multimedia technology containing audio and video has also been shown to promote the development of listening skills (Brett, 1997, Merler, 2000), and computer mediated communication (CMC) has also had positive effects on language acquisition (Chun,1994; Warschauer, 1997). Gulcan (2003), and Hagood (2003) contend that the interplay of multimedia elements improves learning to read a second language. 15 Stenson, Downing, Smith, & Smith (1992) hold the view that visual displays of language learner speech and the opportunity to visually and aurally compare output to that of a native speaker have been shown to improve target language pronunciation. In short, much recent CALL research has focused on the application of CALL in language teaching and research results have showed that CALL can be effectively employed to support and enhance language acquisition. Few, however, have focused on the application of computer software in language learning and teaching. The chief aim of this study was to justify the effectiveness of using computer software to teach English pronunciation to English major students. 1.5. Roles of CALL software in EFL teaching and learning According to Kern (2006), the role of technology in CALL can be thought of in terms of “the metaphors of tutor, tool, and medium”. In the tutor role, computers can provide instruction, feedback, and testing in grammar, vocabulary, writing, pronunciation, and other dimensions of language and culture learning. Voice interactive CALL can also simulate communicative interaction. In the tool role, computers provide ready access to written, audio, and visual materials relevant to the language and culture being studied. They also provide reference tools such as online dictionaries, grammar and style checkers, and concordances for corpus analysis. The Internet and databases can serve as tools for research. In the medium role, technology provides sites for interpersonal communication, multimedia publication, distance learning, community participation, and identity formation. Specifically, Barr (2004) sees the roles of CALL software as follows: - CALL software as a learning aid. Barr (2004) states that generic and specialized computer-assisted learning software have been used to enhance the learning capabilities of students in many areas of study, including language learning. Similar to Kern, Barr also regards computer software as a tutor, “adopting the role of the teacher” and as a tool to develop course materials. 16 - CALL software as a resource for reference According to Barr, CALL software programs are available over the web which can also be directly downloaded. This give tutors the opportunity to prepare lessons using the programs appropriate with aims and objectives of their lessons. Similarly, students are free to browse the web for material or use CALL packages in their own time. Therefore, it can not be denied that information technology in general and CALL software in particular play a positive role in language learning and teaching. In other words, IT and CALL software enhances the process of language learning. 1.6. Benefits of using CALL software in EFL teaching and learning As regards benefits of CALL software, Sciarone and Meijer (1993, quoted in Barr, 2004), suggested that “CALL programs can be used for quite tedious tasks such as teaching grammar and vocabulary acquisition” (p33). CALL programs will never tire, unlike human teachers, and can be used repeatedly. Barr added that when students use CALL packages, the teacher therefore has more time to devote to preparing other types of classes, concentrating on specific problems they may have. In addition, CALL has a certain academic value. Many modern programs make effective use of graphics and color and recorded sound: they are therefore eyecatching, which make students be attracted to the programs that teach tedious areas of language learning. This view is further reinforced by Galavis (1998), who claimed that “Video, pictures, and sound presented by computers stimulate sight and hearing simultaneously in a way traditional resources do not” Galavis goes on to state that CALL software programs may provide considerable input and a wide variety of registers and accents. They “provide access to authentic materials”. Pacoex (1997) also maintains that CALL software is able to offer comprehensible input, which is necessary for the taking place of second language learning. The software utilize a multisensory collection of text, sound, pictures, video, animation and even hypermedia which provide meaningful contexts to facilitate comprehension. 17 As far as the researcher of this study is concerned, the benefits of using computer software in EFL teaching and learning are as follows: The first benefit for using language learning software is the great level of convenience it provides. The software allows students to have a language expert available when they want them to be. In other words, students can use CALL anywhere outside the classroom, in areas of self-study. Another major advantage is that by learning a foreign language using software, students can develop their own autonomy by going at the pace that suits them best and choosing the most appropriate learning styles and strategies. CALL software can also take a load of pressure off students. It can be frustrating and embarrassing to struggle learning a language in front of others that are learning it rather easily. When students learn at home, there is no pressure and no one to feel timid around while learning. Moreover, most of the software for language learning comes along with interactive audio lessons, and even speech recognition software for pronunciation. The more advanced software offerings even come provided with an interactive forum where students can interact with a particular language professional and fellow students. All these characteristics help students to immerse in authentic materials and expose to native speakers. It is due to these benefits of using software in language learning and teaching that the researcher, as a teacher of English of Foreign Language Department at Hong Duc University, decided to exploit the software to teach pronunciation to her first-year English majors. 1.7. Limitations of CALL software in EFL learning and teaching Beside the precious benefits that CALL programs can bring to language learning and teaching, there reveal certain limitations that teachers should take into consideration when choosing these programs to integrate into their lessons. 18 As Graham Davies points out, in his article on history of CALL, that these programs are not suitably spontaneous (2000). In other words, they do not yet have the ability to react to the unforeseen. It students do not understand the mistakes they make, the help sections that many CALL packages provide are limited by the information that the programmer has fed into the help section database. They cannot address questions that have not been pre-programmed. Moreover, “it appears that CALL systems have insufficient technological capability to recognize and respond to the human voice” (Ehsani and Knodt, 1998 quoted in Barr, 2004). Students cannot yet conduct a conversation in a foreign language with a computer: human contact is required for this type of interaction. Galavis (1998) agrees on this fact when he states that computers do not provide some important features of real communicative exchanges as well as the sense of cooperation that can be found in class with a teacher. Lee (2000) also stated that there is a lack of high quality software. To a certain extent, these limitations can be reduced in a number of ways. Levy (1997:231) argues that it is importance for language teachers to have a more direct role in the production of CALL software, thereby, ensuring the pedagogical relevance of these programs. In addition, all the software programs should be carefully checked before being used. 19 CHAPTER 2. METHODOLOGY 2.1. Context of the study The study was conducted at Hong Duc university in Thanh Hoa province. This is a multidiscipline university in which English is one of the majors. Students at Foreign Language Department are trained to become teachers of English for secondary schools in Thanh Hoa. Teachers of English training course K12, to which the study is targeted, is in its first year in the academic year 2009-2010. In the first semester, pronunciation is not designed as a separate subject but integrated into the speaking course which is delivered within 15 weeks with 4 periods a week. The course book being used is “Let’s talk 1” by Leo Jones, Cambridge University Press 2002. My observation at the first and second week of the semester showed that students made many mistakes in their pronunciation. I tried to correct some of these mistakes. However, students seemed so solidly stuck to their initial pronunciation that right after the teacher’s feedback, they returned to their mistakes. Therefore, I decided to provide them with proper training using the software packages that are vivid enough to change their fossilized mistakes. 2.2. Arguments for the use of an action research “Action research is any systematic inquiry conducted by teacher researchers to gather information about the ways that their particular school operates, how they teach, and how well their students learn. The information is gathered with the goals of gaining insight, developing reflective practice, effecting positive changes in the school environment and on educational practices in general, and improving student outcomes.” (Mills, 2004:4) According to Cohen and Manion (1985), the aim of action research is to improve the current state of affairs within educational context in which the research is carried out. 20 Koshy (2005) also maintains that action research is a powerful and useful model for practitioner research because research can be set within a specific context or situation and researchers can be participants – they do not have to be distant and detached from the situation. The researcher, as a teacher, decided to choose action research as her methodology because action research is classroom-based research conducted by teachers in order to reflect upon and evolve their teaching. This meets the main purpose of my thesis, that is to gain understanding of teaching and learning within my own classroom and to use that knowledge to increase my teaching efficacy and improve my own students’ pronunciation. 2.3. Description of the software program Pronunciation Power series consisting of 2 CD-Roms is an interactive software program that focuses on developing students’ individual sounds and basic suprasegmental features. There are three areas of study for a particular sound: Lessons, Speech Analysis, and Exercises. Pronunciation Power 1 contains S.T.A.I.R. (Stress, Timing, Articulation, Intonation and pitch, and Rhythm) Exercises which are not available in Pronunciation Power 2. Audible sounds are accompanied by visual illustrations (a side and a front view) of real-time articulatory movements for the production of the sounds. For the side view, animated drawings provide an x-rayed look of the complete articulatory mechanics, including manner and location of airflow, lips and tongue placement and movement, velum movement, and whether a sound is voiced or voiceless. For the front view, a video clip of a real person is shown, demonstrating jaw, lip, and tongue protrusion movement. A written description, and at times suggestions, for producing the sound is provided, which the user can access as an auditory clip. The Speech Analysis offers the user a look at graphic representations of the sound utterance as a waveform. The user is able to record their own production of the sound, and then compare their waveform of the sound with that of the instructor. The waveforms provide information concerning the loudness (amplitude) and pitch (frequency) of sounds, as well as duration (length). 21 2.4. Subjects of the study The researcher is a teacher of Foreign Language Department at Hong Duc University. The students participating in the research were 30 first-year English majors from K12 - teacher training course, academic year 2009-2010 of Foreign Language Department at Hong Duc University. They consist of 29 girls and 1 boy, who are between 18 – 20 years of age. They come from different districts in Thanh Hoa and have learned English for 7 years or more. They must get at least mark 5 for English in order to pass the entrance exam. Therefore, it can be assumed that these students are quite homogeneous in their level of English proficiency. 2.5. Instruments The full period of data collection covered the whole term in order to help me see the effects of my interventions. Three different methods were used, of which classroom observation and informal interviews with the students were carried out through the whole term and the other one, audio-recording at the beginning as a pre-test and the end of the term as a post-test. Classroom observation My observation fell on the following aspects: - Students’ accurate pronunciation of sounds. - Students’ word stress and sentence stress. - Students’ use of rhythm unit. - Students’ intonation My observation was noted down in my teaching journals after each lesson. Informal interview with students 22 Throughout the whole term, I conducted informal interviews with my students during class breaks. My major concerns are their opinions of the new way of presenting the pronunciation using the software, and how useful they think it is. Information obtained from my students was also included into my teaching journals. Audio-recording This is the main instrument to collect the needed information in my research which were administered to students at the second week and final week of the semester. The purpose of the first audio-recording is to find out students’ typical pronunciation mistakes regarding sounds, stress, rhythm and intonation. The second audio-recording is aimed at investigating the effectiveness of using CALL software in teaching pronunciation. 2.6. Procedure The study was conducted during the first term of the academic year 2009-2010. At the beginning of the semester, a pretest was conducted to the students to find out the current situation of their pronunciation. Then the intervention was provided. During the pronunciation and speaking classes, the teacher used the CALL software package named Pronunciation Power to give students explicit instruction on how to pronounce different sounds, to put stress on words or in sentences, to speak with the right rhythm and intonation in English. Then the students practiced with the help of the software to achieve native-like pronunciation. At the end of the semester, a post-test was administered to these students to discover whether the intervention had any positive effect on their pronunciation. Furthermore, from the very first lesson of the course, the teacher kept the record of the students’ pronunciation in classroom activities in her teaching journals, which lasted for a whole term. By the end of the term, 15 records of teacher observation will be collected. In the class breaks during the term, informal interviews with the students were carried out and also kept in the teacher’s teaching journals. Based on the results of the audio-recording as well as the teacher’s observation and informal interviews with the students,, the efficiency of the intervention was evaluated. 23 CHAPTER 3. DATA ANALYSIS, FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION 3.1. Findings from the pretest In the second week of the semester, students participated in the pretest in which they were given a passage, or single sentences to read and short conversations to practice speaking in pairs. The reading passage was taken from How to Prepare for the TOEFL by Palmela J.Shape, PhD, 9th edition, Nha xuat ban tre (2000), and the short conversations from Life Line Pre-intermediate, Life Line Intermediate by Tom Hutchinson, Oxford University Press 2002 and English Pronunciation In Use by Mark Hancock, Cambridge University Press, 2003. The audio scripts of these were used as the standard tool for the analysis of the students’ pronunciation (see appendix). Students’ reading and speaking were recorded and then compared to the model patterns. 3.1.1. English sounds The purpose of the reading passage was to find out students’ common mistakes in producing individual sounds. It was not randomly chosen but contained a lot of sounds that the researcher, in her preliminary investigation, found that the students were weak at. The results showed the following facts. In terms of vowels, students do not have the distinction between long and short vowel pairs of English. They tend to produce the two vowels of each pair identically. In addition, students are bound to have problem with the sound /æ/ which is often produced in a similar manner to the sound /e/ or / /. As regards consonants, students seem to have more troubles. The first common mistake is that students omit the final consonant clusters such as /d/ in ‘brand’, / t in ‘washed’, /ld/ in ‘traveled’, /ksts/ in ‘texts’ etc… Then, the sounds / / and /ð/ are also problematic for these students. They substitute ‘th’ and ‘d’ in Vietnamese for / / and /ð/ in English respectively. The next common mistake is with the sounds /t /, / /, /d / and / /. /t / is pronounced like ‘ch’, / / like ‘s’, /d / and / / like ‘d’ in Vietnamese. The detailed numbers and corresponding proportion of students who made these mistakes are shown in the table below. 24 Table 2. Students’ common mistakes in producing English sounds Kind of Mistakes Number of Percentage students 1. Producing long and short vowel pairs identically 26 87% 2. Pronouncing /æ/ like /e/ or / / 25 83% 3. Omitting final consonant clusters 26 87% 4. Producing / / like ‘th’ and /ð/ like ‘d’ 24 80% 5. Having wrong pronunciation with /t / 20 67% 6. Having wrong pronunciation with / / 17 57% 7. Having wrong pronunciation with /d / 16 53% 8. Having wrong pronunciation with / / 16 53% 3.1.2. Stress As regards stress on important words, the result is shown in the table 3 below. Table 3. Students’ stress on important words Sentence 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Model OooOo oOoooO ooOoO OooO ooOoO oOoO ooOooO Number of 10 7 9 11 8 11 7 correctness Percentage 33% 23% 30% 37% 26% 37% 23% The figures in table 3 represents that the number of students who put the right stress on important words is not high. Sentence 4 and 6 receive the most correct responses from 25 students but the percentage of correctness is only 37%. Moreover, from my own observation during the test, the correct stresses seem to be restricted within better students. What made me wonder was that although all the sentences have two stresses, students tended to speak with the right stress on this sentence but not with the others. I asked my students the reasons for this. It was surprising when many students confessed that they just role-play the conversation the way they liked. They did not actually know which words should receive stress. In terms of stress on corrective words, the result is reported in the following table. Table 4. Students’ stress on corrective words Sentence Model 1 2 3 4 ooooooOooooOooO oooooooOoOooOooo oooooooOOOo ooOoooooooOOo Number of 4 4 7 5 correctness Percentage 13% 13% 23% 17% As can be seen from table 4, the problem with students’ pronunciation is even more serious when it comes to stress on corrective words. The majority of students did not employ the correct stress positions in these sentences. Sentence 3 had the most students’ correct stress positions, which made up 23% of the total number. Sentence 1 and 2 had a equal number of students who put the right stress on corrective words, which accounted for 13%. When being asked what they knew about corrective stress, most of the students acknowledged that they had never heard of it before. This really explained why so many students had mistakes with corrective stress. In addition, it is surprising that even some of the students who had the correct responses admitted that they just put stress at random positions and their performance is accidentally correct. 26 3.1.3. Rhythm and thought groups When being tested on rhythm in English, the students really revealed their weaknesses. The chart below shows the problems they had with rhythm. Chart 1: Rhythm and thought groups 30 N o .o f students 25 20 15 10 5 0 misplaced stress misplaced pauses more pauses than model less pauses than model syllable-timed rhythm The biggest problem students had was misplaced pauses. 24 of them did not have the appropriate pauses. They just paused somewhere in the middle of the sentence when they wondered about word stress. The next reason why students did not have the right rhythm is misplaced stress. 21 students did not put stress on the right words. Furthermore, even those with the right stress tended to produce a typical Vietnamese rhythm, that is syllable-timed rhythm. Other reasons include students making more or less pauses than the model. 3.1.4. Intonation Because the aim of the study is to improve first-year English major students’ pronunciation, not all aspects but only the basic patterns of intonation in common functions are included in the pretest. As for intonation of statements, yes-no questions, wh-questions, requests and suggestions, the results are shown in the table below. 27 Table 5. Students’ intonation of statements, yes-no questions, wh-questions, polite requests and suggestions Sentence 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 No. of correct patterns 25 20 16 16 11 19 14 Percentage 83% 67% 53% 53% 37% 63% 47% Model As can be seen from table 5, 25 students, which accounts for 83% of the total 30 students, could produce a statement – sentence 1 with the right patterns. It means that most of these students did not have much trouble with the intonation of statements. However, when it comes to yes-no questions, wh-questions, requests and suggestions, the number of right patterns falls down. Sentence 5, which is a polite request receive the lowest number of correct patterns. Only 11 students, which made up 37%, could pronounce this request properly. Besides, my informal interview with these students revealed that many of them knew the intonation pattern of yes-no questions but they could not put it into real speaking. The fact is that they produced yes-no questions with a flat intonation or with a rising tune but in unnatural way. Most of them, however, did not know how to pronounce polite requests and suggestions precisely. With regards intonation of lists, the result is represented in table 6. Table 6. Students’ intonation of lists Sentence 1 2 3 4 5 No. of correct patterns 15 10 13 9 13 Percentage 50% 30% 43% 30% 43% Model The figures in table 6 show that the majority of students made mistakes with the intonation pattern of listing. It seems that the longer the list is, the more difficult it is for students. This is demonstrated when sentence 2 and 4 had the least correct patterns, with 10 correct patterns for 28 the former and 9 for the latter. Most of the students produced the list with a falling tune. They argued that it is because these sentences are statements. 3.1.5. Linking The final part of the pre-test examines students’ use of word linking, the result is reported in table 7 below. Table 7. Students’ performance of word linking Sentence 1 2 3 4 5 No. of correct responses 14 13 12 12 10 Percentage 47% 43% 40% 40% 33% From the table we can see that numerous students do not link the final consonant of the previous word with the initial vowel of the following one. Sentence 1 receives the highest number of correct responses, accounting for 47%. Some students admitted that they know the rule but do not remember to apply it in real speaking. In summary, the results of the pretest demonstrate that the majority of students encounter difficulties with both segmental and suprasegmental features of English pronunciation. It is necessary that something be done to help them improve their pronunciation. The researcher as a teacher decided to choose the software Pronunciation Power to be exploited in her pronunciation lessons. The teaching program is presented in the next part. 3.2. The intervention The intervention took place during the first semester of the academic year 2009 – 2010. Based on her preliminary class observation and the results of the pretest, the researcher chose appropriate parts of the software to deal with students’ pronunciation weaknesses. The detailed intervention is shown in the following table. 29 Table 8. Aspects of pronunciation to be integrated in speaking lessons Week Aspects of pronunciation to be integrated in speaking lessons 1 The researcher’s preliminary investigation 2 Introduction to the research program 3 Long and short vowel pairs 4 Vowels /æ/ vs. /e/ and / 5 The consonants / / and /ð/ 6 The consonants /t / and / / 7 The consonants/d / and / / 8 Final consonants clusters 9 Stress 10 Rhythm 11 Intonation of statement, yes-no questions, wh-questions 12 Intonation of suggestions, polite requests 13 Intonation of listing 14 Word linking 15 Closure of the program / vs. / / The intervention took place in the LAB ROOM of the Foreign Language Department at Hong Duc University. This room is equipped with a central computer which is connected with the projector and 30 personal computers. All these thirty-one computers are linked through LAN system. From week 3 to 14, at the beginning of the speaking lessons, one aspect of pronunciation was presented on the big screen. After eliciting from the students, the teacher 30 explained and recapitulated using explicit instructions. Finally, the students reviewed and practiced using the personal computers with the help of the teacher. 3.3. Findings from the post-test At the end of the semester, the post-test was conducted to discover whether the students had made any improvement in their pronunciation. The posttest is similar to the pre-test in structure (see appendix). Students’ pronunciation was also recorded for analyzing and comparing with the pretest results. 3.3.1. English sounds The result of the students’ pronunciation of English sounds in the posttest was compared with that in the pretest as follows: Table 9. Comparison of the students’ pronunciation of English sounds in the pretest and posttest Kind of Mistakes Pretest No. of Posttest Percentage students No. of Percentage students 1. Producing long and short vowel pairs 26 87% 8 27% identically 2. Pronouncing /æ/ like /e/ or / / 25 83% 14 47% 3. Omitting final consonant clusters 26 87% 13 43% 4. Producing / / like ‘th’ and /ð/ like ‘d’ 24 80% 5 17% 5. Having wrong pronunciation with /t / 20 67% 6 20% 6. Having wrong pronunciation with / / 17 57% 5 17% 7. Having wrong pronunciation with /d / 16 53% 8 27% 8. Having wrong pronunciation with / / 16 53% 8 27% 31 In general, the figures in the table show that the number of students making mistakes with individual sounds significantly decreases after the intervention. While 26 students (accounting for 87%) failed to distinguish long and short vowel pairs in the pretest, only 8 students (accounting for 27%) had this problem in the posttest. The sounds / / and /ð/ also seems manageable for the students when the number of students making mistake with these sounds sharply decreases from 80% to 17%. Moreover, the sounds /t / and / / also witnessed a positive change in the students’ pronunciation. 20% of the total number made mistake with the sound /t / and 17% with the sound / / in the posttest in comparison with 67% and 57% respectively in the pretest. However, the sound /d / and / / seem more difficult for these students because little improvement was made. Among 16 students who made mistake with these sounds in the pretest, only 8 could make progress while the other 8 kept their initial wrong pronunciation. It appears that the sound /æ/ is the most problematic for the students. After the intervention, 47% of the students could not make any improvement with this sound. They still produced this sound like /e/ or / /. Final consonant clusters are also the problematic issue. 43% of the students kept omitting final consonants when speaking. My informal interviews with these students showed that they knew they had to pronounce final consonants in English and they could do it when pronouncing individual words but they just missed in speaking or reading long passages. In short, it can be concluded that the intervention has some positive effects on improving students’ pronunciation of English sounds. Students made great progress with the distinction between long and short vowel pairs. Their pronunciation of the sound / /, /ð/, /t /, and / / also significantly improved. Nevertheless, little improvement is found for the pronunciation of the sound /æ/ and final consonant clusters. 3.3.2. Stress 32 Different from the pretest which consists only sentences with 2 important words, the posttest includes sentences with two or more than two important words. Students’ performance in the posttest regarding stress on important words is shown in the following table. Table 10. Students’ stress on important words Sentences 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Model oOoooO oooOOooOoo oOooOoOoO oOoOo OoOO ooOoooOoOo Ooooo Number of 25 19 20 24 28 18 29 correctness Percentage 83% 63% 67% 80% 93% 60% 97% The figures in table 10 show that the longer the sentences are, the fewer correct responses there are. Sentence 2 and 6, which are the longest sentences, received the least correct answers, only 19 for sentence 2 and 18 for sentence 6 (accounting for 63% and 60% respectively). Whereas, sentence 7, a short and simple one, got 29 correct responses which made up 97% of the total. Whatever, the number of correctness increases considerably in comparison with that in the pretest in which the highest number of correctness is only 11 (accounting for 37%). Table 11 below describes students’ performance regarding stress on corrective words. Table 11. Students’ stress on corrective words Sentence Model 1 2 3 4 oooooooOooOoooOo ooooOooooooooOoOo oooOoooOoOooo oooOoooooOO Number of 19 23 21 25 correctness Percentage 63% 77% 70% 83% 33 When compared with the result in the pretest, it came to me as a surprise that students’ performance regarding stress on corrective words in the posttest was remarkably better. The number of students who could put the right stress on corrective words increases dramatically. The highest number of correctness in the posttest is 25 (83%) for sentence 4 in comparison with 7 (23%) in the pretest. For the other sentences, the number of correctness is also quite high with 23 for sentence 2, 21 for sentence 3 and 19 for sentence 1 which account for 77%, 70 and 63% respectively. My teaching diary shows that students found the rule to put stress on corrective words easy to remember. They did not perform well in the pretest just because they had not been taught the rule before. 3.3.3. Rhythm and thought groups Chart 2 shows the comparison between the students’ performance in the pretest and posttest regarding rhythm and thought groups. Chart 2. Rhythm and thought groups 30 N o . o f s t u d e n ts 25 20 pretest posttest 15 10 5 0 misplaced stress misplaced pauses more pauses than less pauses than model model syllable-timed rhythm It seems that rhythm is rather difficult for the students to master because the number of students who made mistakes did not decrease much in the posttest. In terms of misplaced stress, the number falls from 21 to 15 which means that only 6 students achieved progress. For misplaced pauses, 17 students still made mistake in the posttest in comparison with 24 in the 34 pretest. The other two also witnessed students’ little improvement with 11 students using more pauses and 13 using less pauses than required as compared with corresponsive 15 and 17 in the pretest. Moreover, only 5 students managed to abandon their syllable-timed rhythm. It can be said that students’ performance of rhythm gained the least improvement among the aspects of pronunciation being taught during the semester. 3.3.4. Intonation The result of the students’ intonation of statements, yes-no questions, wh-questions, polite requests and suggestions is reported in table 12. Table 12. Students’ intonation of statements, yes-no questions, wh-questions, polite requests and suggestions Sentence 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 No. of correct patterns 30 27 25 26 22 27 26 Percentage 100% 90% 83% 87% 73% 90% 87% Model As the researcher had expected, the students performed strikingly well in this part. 30 students (100%) could produce sentence 1, which is a statement, with the right pattern. This is explainable because up to 25 students (83%) could pronounce a statement correctly in the pretest. Futhermore, sentence 2, a wh-question and sentence 6, a suggestion both received 27 correct patterns which made up 90%. For yes-no question –sentence 3 and suggestion in the form of yes-no question - sentence 7, the students also made progress with 25 correct patterns for the former and 26 for the latter in comparison with 16 and 14 respectively in the pretest. However, making a polite request seems more difficult than the others with the least correct patterns, 11 in the pretest and 22 in the posttest. One more finding is that the students were more likely to produce falling tune correctly than rising tune. All in all, the students’ intonation of statements, yes-no questions, wh-questions, polite requests and suggestions has greatly improved at the end of the research program. 35 As regards the students’ intonation of lists, the result is in the following table. Table 13. Students’ intonation of lists Sentence 1 2 3 4 5 No. of correct patterns 25 28 28 27 26 Percentage 83% 93% 93% 90% 87% Model Beyond the researcher’s expectation, the students have made excellent progress in pronouncing lists. For sentences with two items in the list such as sentence 2 and 3, almost all students could speak with the right patterns (28 for both sentences) while only 15 could in the pretest. For other sentences with more than two items in the list, the number of correct patterns is also considerably high (from 25 to 27 correct patterns) in comparison with that in the pretest (from 9 to 13 correct patterns). The unchanged thing is that the longer the list is, the more difficult it seems for the students. That is why sentence 1 with the longest list received the least correct patterns. 3.4.5. Linking The students’ performance of linking in the posttest is shown in table 14 below. Table 14. Students’ performance of word linking Sentence 1 2 3 4 5 No. of correct 25 26 24 25 26 83% 87% 80% 83% 87% patterns Percentage The figures in the table shows that the students could perform much better in the posttest than in the pretest. The highest number of correct responses in the posttest is 26 in comparison with 36 14 in the pretest However, the teacher’s observation showed that although the students could link the sounds together, their speech is not natural and they often stopped to think when they started to produce the linking. Therefore, it can be concluded from all the above findings that the students’ intonation regarding statements, yes-no questions, wh-questions, polite requests, suggestions, lists, old and new information has experienced significant improvement after the researcher’s intervention. In summary, the following conclusions are drawn from the data collected in the posttest. To start with, the students have actually made recognizable progress with English sounds, especially the distinction between long and short vowel pairs, and the sounds / /, /ð/, /t /, / /. However, little improvement is seen for the sound /æ/ and final consonant clusters. Moreover, the students’ performance of stress has also greatly improved. After training of stress in association with parts of speech, students’ awareness of stress on important words has been raised to a much higher level. However, longer sentences with more stressed words still seem to make students confused. Also, the training of stress on corrective words has helped students to make impressive improvement in their performance. As regards English rhythm, it seems to be the most difficult aspects to be mastered. Students gained the least improvement because they misplaced stress, misplaced pauses or produced with syllable-timed rhythm. Finally, on the part of intonation, statements and wh-questions received the most correct patterns. This is understandable because they are most common in everyday language and the falling tune at the end of the sentence is familiar, so easier for the students to produce than the rising tune. The students’ intonation of lists and old information also remarkably improved at the end of the research program. What seems to be the most difficult for the students to make progress is the polite request with the least improvement. Teaching diary points out that the students use the rising tune but not as polite as it needs. 37 All in all, as a result of the intervention, the students’ pronunciation has considerably improved. The teacher’s observation also shows that students could speak more naturally with more accurate sounds, appropriate stress, and intonation though rhythm needs more training and practice for better performance. The results of the study support the view by Stenson, Downing, Smith, & Smith (1992) that the use of software with visual displays of language learner speech and the opportunity to visually and aurally compare output to that of a native speaker can improve target language pronunciation. Furthermore, the findings of this study fairly corresponds with the assumption Derwing, Munrol and Wiebe (1998) have made, that is, explicit instruction is essential in teaching pronunciation. Explicitly teaching learners about the features of pronunciation will help them master the features faster than letting them pick up the features through exposure to the language, particularly in a foreign language context. Therefore, it is necessary for ESL teachers to draw learners’ awareness to these features and to provide them with explicit training. On the other hand, the results of the study are also consistent with the findings in my related investigations (Levis, 2005; Saito, 2007) that segmental should be taught prior to suprasegmental features. This result does not mean that students do not have the ability to perceive the suprasegmental features at the initial stage, but that they need to have basic understanding of sounds before moving into the more complicated issue of prosody. 3.4. Further findings from the teacher’s observation and informal interview with students The teacher’ observation during class hours and informal interviews with the students during breaks were conducted as supplementary instruments in order to find out how students learnt pronunciation with the help of software, how they evaluated the new way of using the 38 software to present pronunciation lessons, and how useful they thought it was. The findings are as follows. Firstly, the students held the new way of teaching pronunciation in high regard. They acknowledged that the use of software in teaching and learning pronunciation did a great help in improving their pronunciation. The audible sounds accompanied by visual illustrations (a side and a front view) of real-time articulatory movements for the production of the sounds really helped them master the way to pronounce difficult sounds and distinguish similar sounds. The function that the Speech Analysis offers the user a look at graphic representations of the sound utterance as a waveform helped the students a lot in evaluating their pronunciation accuracy by comparing their waveform of the sound with that of the instructor. Secondly, during the class hour with the exploitation of software, the students were highlymotivated. They took part in the lesson actively and enthusiastically. All the students held a positive attitude towards using software in pronunciation lessons. The informal interviews with the students revealed that the reasons for their high motivation consisted of the their interest in the new learning environment and authentic input, opportunity to learn at their own pace, and vivid images and sounds. However, using the software Pronunciation Power in teaching pronunciation also reveals some disadvantages. At the beginning of the project, the students complained about some difficulties which are mainly related to technical issues such as being unfamiliar with some computer functions, or being unable to run the software. However, these problems were easily solved by the teacher’s instructions. 39 PART III. CONCLUSION 1. Summary So far, this study has answered the three research questions what the students’ most common problems regarding their English pronunciation are, whether Pronunciation Power is effective in teaching first-year English majors’ pronunciation and how effective it is. An action research project has been conducted in a speaking and pronunciation course in the first semester for the 30 first-year English majors of Foreign Language Department at Hong Duc University. The project involved exploiting the computer software entitled Pronunciation Power to provide students with explicit instruction on English sounds, word stress, sentence stress and rhythm, intonation and relevant exercises for them to practice. The instruments used for obtaining the data consisted of a pretest at the beginning and a posttest at the end of the semester, classroom observations, and informal interviews with students. The researcher’s initial investigation and the pretest results showed that the students’ difficulties concerns long and short vowel pair distinction, and the sounds that do not exist in Vietnamese such as /æ/, / /, /ð/, /t /, / /, /d /, and / /. Furthermore, stress, rhythm and intonation are also the students’ weaknesses. The intervention took place from week 3 to week 14 of the semester. The findings from the posttest results, teacher’s observation and informal interview with students showed that the intervention helps improve English pronunciation for first-year English majors at Hong Duc University. 2. Pedagogical implication The findings of the study implicate that - CALL software packages should be integrated in teaching and learning English pronunciation in order to increase the quality of EFL education as well as to keep along with the present teaching trend in the world. 40 - Technical investment for English teaching and learning should be paid more attention. For the time being, there is only a LAB room which is fully equipped with computers at Hong Duc university. More classrooms like this one should be installed so that all the English majors of Foreign Language Department have opportunity to learn English in a new learning environment. - During the first lessons with the application of CALL software packages, the students could face some difficulties with the computers. The teacher should take this into consideration before using the software and be ready to give the needy students timely support. - This study can be used as a reference source for teachers, learners and those interested in using software programs in teaching and learning English pronunciation. 3. Limitations of the study Although the study has some beneficial contributions to the pronunciation teaching and learning, it still has some limitations as follows. First, as an action research with its typical characteristic defined as ‘situational’, this study is prone to lack generalization. The intervention has worked quite successfully in the researcher’s class but may not be applied to other classes in other contexts. This research, therefore, has unavoidable limited application. Furthermore, since the researcher could not control all the variables and constructs during the research project, the question whether software can improve students’ pronunciation is still not absolutely answered. Students’ improvement may result from other factors such as their high motivation, time devotion, learning from other classes or self-learning, ect… Last but not least, the size of the study is rather small with only 30 first-year English major students. This number is not enough to have a full understanding of pronunciation difficulties that first-year English majors encounter. 41 4. Suggestions for further research The study has opened some directions for future research. (1) After the study has been conducted to first-year English majors at Hong Duc university, it should be conducted to other first-year English majors at other universities as well. Then the effectiveness of using the software Pronunciation Power in teaching English pronunciation will be more accurately evaluated. (2) Beside the software Pronunciation Power, there exists other software packages used to teach English in general and pronunciation in particular. The effectiveness of these packages should be tested so that they can be widely used in EFL teaching and learning. Hopefully, this study and subsequent research will result in better awareness and evaluation of applying software in teaching and learning English pronunciation, so that contribute to the renovation of EFL teaching methods at Hong Duc University. 42 REFERENCES Avery, P., & Ehrlic, S. (1992). Teaching American English Pronunciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press Barr, D. (2004). ICT – Integrating Computers in Teaching. Peter Lang. Brett, P. (1997). A comparative study of the effects of the use of multimedia on listening comprehension. System, 25, 39–53. Celce-Murcia, M., Brinton, D., and Goodwn, J. (1996). Teaching Pronunciation. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chun, D. (1994). Using computer networking to facilitate the acquisition of interactive competence. System, 22, 17–31. Cohen, L., and Manion, L. (1985). Research Methods in Education. London: Croom Helm. Couper, G. (2003). The value of an explicit pronunciation syllabus in ESOL teaching. Prospect, 18 (3), 53 - 70. Dalton, C. & Seidhofer, B. (1994). Pronunciation. Oxford University Press.Dewing, T., & Munro, M. (2005). Second language accent and pronunciation teaching: A research-based approach, TESOL Quarterly, 39 (3), 379 - 397 Davies, G. (2000). Lessons from the past, lessons for the future: 20 years of CALL. Accessed on World Wide Web, August 2000. Achieved March 20th 2010 from http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/grahamdavies1/coegdd1.htm Dewing, T., & Munro, M., Wiebe, G. (1997). Pronunciation instruction for "fossilized" learners: Can it help? Applied Language Learning, 8, 217 - 235 Field, J. (2005). Intelligibility and the Listener: The Role of Lexical Stress. TESOL QUARTERLY, 39(3), 399 – 423. Galavis, B. (1998). Computers and the EFL Class: Their Advantages and a Possible Outcome, The Autonomous Leaner. English Teaching Forum, 36 (4), P27. Gulcan, E. (2003). Exploring ESL: Learner’s use of hypermedia reading glosses. CALICO Journal, 3(4), 75–91. Hagood, M. C. (2003). New media and online literacies. Research Quarterly, 38, 387–391. Hancock, M. (2003). English Pronunciation in Use. Cambridge University Press 43 Hahn, L.D. (2004). Primary Stress and Intelligibility: Research to Motivate the Teaching of Suprasegmentals. TESOL QUARTERLY, 38(2), 202 – 203Hewings, M. (2004). Pronunciation Practice Activities. Cambridge University Press. Jull, D. (1992). Teaching Pronunciation: An Inventory of Techniques, in Every, P. and Ehrlich, S. (eds.), Teaching American English Pronunciation. Oxford University Press, pp.207-214.Kelly, G. (2000). How to Teach Pronunciation. Longman Koshy, V. (2005). Action Research for Improving Practice .SAGE Publications Inc. Kelly, G. (2000). How to Teach Pronunciation. Longman. Kenworthy, J. (1987). Teaching English Pronunciation. Longman Lee, K. (2000). English Teachers’ Barriers to the Use of Computer-Assisted Language Learning. The Internet TESL Journal , 6 (12). Retrieved 20th March, 2010 from http://iteslj.org/Articles/Lee-CALLbarriers.html Levis, J.M. & Grant, L. (2002). Integrating Pronunciation into ESL/EFL Classrooms. TESOL JOURNAL,12 (2), 13. Levis, T. (2005).Changing contexts and shifting paradigms in pronunciation teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 39 (3), 367 – 377 Levy, M. (1997). Computer-Based Language Learning: Context and Conceptualization. Oxford: Clarendon. Luchini, P. (2005). Task-Based Pronunciation Teaching: A State-of-the-art Perspective. Asian EFL Journal, 7(4), 193-195. Retrieved May 25, 2009 from http://www.asian-elfjournal.com. Macdonald, D., Yule, G., Powers, M. (1994). Attempts to improve English L2 pronunciation: The variable effects of different types of instruction. Language Learning, 44, 75 – 100 Mathew, T (1997). The influence of pronunciation training on the perception of second language contrast. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 35(2), 223 - 229 Martin H. (2004). Pronunciation Practice Activities. Cambridge University Press Merler, S. (2000). Understanding multimedia dialogues in a foreign language. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 16(2), 148–159. Mill, G.E. (2003). Action Research: A guide for the Teacher Researcher. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall 44 Murphy, J. (1991). Oral communication in TESOL: Integrating listening, speaking, and pronunciation. TESOL Quarterly, 25, 51-74 Nikolova, O. (2002). Effects of students’ participation in authoring of multimedia materials on student acquisition of vocabulary. Language, Learning & Technology 6(1), 100–122. Retrieved May 10, 2006, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol6num1/NIKOLOVA/default.html Naiman, N. (1992). A Communicative Approach to Pronunciation Teaching, in Every, P. and Ehrlich, S. (eds.), Teaching American English Pronunciation. Oxford University Press, pp.163-171. Pascoex, M.E.B. (1997). Technology and Second Language Learners. American Language Review. 1(3). Retrieved March 20th ,2010 from http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/think/resources/knowledge_net1.shtml Roach, P. (1998). English Phonetics and Phonology. Penguin English. Saito, K. (2007). The Influence of Explicit Phonetic Instruction on Pronunciation in EFL Settings:The Case of English Vowels and Japanese Learners of English. Linguistics Journal, 3(3), 19. Retrieved December 20, 2008 from http://www.lingistics_journal.com. Sifakis, N.C. & Sougari A.M. (2005). Pronunciation Issues and EIL Pedagogy in the Periphery: A Survey of Greek State School Teachers’ Beliefs. TESOL QUARTERLY, 39(3), 469 – 470. Stenson, N., Downing, B., Smith, J., & Smith, K. (1992). The effectiveness of computerassisted pronunciation training, CALICO Journal, 9(4), 5–20. Stevick, E.W. (1978). Toward a practical philosophy of pronunciation: Another view. TESOL Quarterly, 12, pp.145-150. Ur, P. (1996). A Course in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer-mediated collaborative learning: Theory and practice. The Modern Language Journal, 81, 470–481. Wood, J. (2001). Can software support children’s vocabulary development? Language, Learning & Technology 5(1), 166–201. Retrieved January 10, 2010, from http://llt.msu.edu/vol5num1/wood/default.html Zhao, Y. (2003). Recent developments in technology and language learning: A literature review and meta-analysis. CALICO Journal, 21(1), 7–27.