a guide to price inflation - American Institute for Economic Research

advertisement

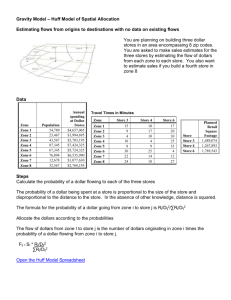

Vol. XXXI No. 12 Published by AMERICAN INSTITUTE ECONOMIC EDUCATION BULLETIN December for ECONOMIC RESEARCH Great Barrington, Massachusetts 01230 1991 A GUIDE TO PRICE INFLATION A dollar isn't what it used to be. As measured by changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), the general price level has increased more than eight times since 1930. To buy the same value of goods and services that a dollar commanded in 1930 you now need $8.15; today's dollar buys only what 12 cents did 60 years ago. Over shorter periods prices have increased less rapidly, but the cumulative effect of even moderate price inflation can be severe — perhaps more severe than many people may realize. For example, during the past 5 years, when price inflation averaged 4.4 percent per year and was widely regarded as being "under control," the purchasing power of the dollar dropped by 20 cents. As shown in the tables on the following pages, the rate of price inflation has varied over the years and has fluctuated with economic cycles, but the long-term trend has been upward. During the 43 years ending 1991, the increase in the CPI has been as follows: Period 1948-1962 1962-1976 1976-1991 CPI +26.1% +91.4% +136.8% The effect of these price increases has been felt unevenly by those who hold dollars and use them for transactions. In general, individuals or businesses "locked in" to fixed-dollar contracts suffer or benefit the most when price inflation exceeds expectations. The "winners" are those who contracted to pay out fixed amounts of dollars in the future, since they pay with dollars of reduced purchasing power. The "losers" are those who are obligated to accept future payments of dollars. Past "winners" include long-term borrowers with fixedrate contracts. These include not only private borrowers (for example, the home buyers of the 1960's who took out 20year mortgages at 6 percent interest), but also public borrowers, most notably the Federal Government (which is still paying 3.5 percent interest on bonds issued in 1960). The "losers" have included the savings and loans institutions that "borrowed short and lent long" in the 1960's and 1970's, and many individuals who purchased Government bonds. Pensioners and annuitants who receive fixed-dollar incomes have also suffered from the degradation of the currency. Other winners and losers in the "inflation game" and their gains and losses are more difficult to identify. This is partly because price increases attributable to the excess creation of purchasing media do not affect all goods and services to the same extent. People who buy the items whose prices increase fastest (such as medical and educational services in the 1980's) suffer a relatively larger erosion in the purchasing power oí their dollars; people who supply these items may actually gain. In addition, some items, such as financial assets and real estate, are not directly included in standard statistical measures of price inflation, and thus it is difficult to gauge the impact of their price changes on the "cost of living." Moreover, price inflation affects people differently nowadays than it did years ago, due to the increased use of "inflation hedges." Cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs), "inflation-indexing," and adjustable-rate loans have shifted some of the cost of price inflation away from those who traditionally were harmed by it to those who used to benefit from it. For example, adjustable-rate loans have reduced both the potential losses to lenders and the gains to borrowers in the event that prices increase faster than expected. However, it is virtually impossible to protect all of one's financial transactions, income and assets from the effects of price inflation. Most employers offer COLAs to employees only on an ad hoc basis, if at all. The adjustments are sometimes inadequate, and there is no guarantee that they would be provided if price inflation returned to the "double digits." Company-sponsored pension benefits are rarely if ever adjusted, and annuities are not indexed at all. Federal income tax brackets are indexed annually, but many deductions and credits are not (e.g., the maximum IRA deduction, which has been fixed at $2,000 since 1981; if it were indexed it would now be $3,000). Long-term investors, in particular, are still very vulnerable to accelerating price inflation. On the one hand, capital gains are not indexed on U.S. tax returns, even though many such gains simply reflect rising prices and not any real income gains. On the other hand, investors who buy longterm fixed-rate bonds are essentially gambling that the "inflationary expectations" reflected in their interest rate will be accurate. If prices increase faster than the "conventional wisdom" anticipates, long-term investors stand to lose — and long-term borrowers stand to gain. In this respect, it is notable that the largest and fastestgrowing borrower in the United States is the Federal Government. Current U.S. public debt stands at $2.4 trillion, or 48 cents for every dollar of GNP. Interest payments on this debt have increased sharply in recent years. In 1990 the Government paid $184 billion in net interest. These outlays accounted for 14.7 percent of total Federal spending, compared to 8.5 percent in 1979. In relation to Gross National Product, interest outlays during this period increased from 1.7 percent to 3.5 percent. As the burden of financing this growing debt increases, so will the pressure to "inflate it away." And as long as politicians and money managers have the power to issue currency by fiat, this option will be available to them. If and when this happens — and there has never been a fiat currency that did not eventually devolve into worthlessness — the impact on income and wealth that is not pro- Table A TODAY'S DOLLARS $1 $20 $500 $1,000 and their equivalent purchasing power in earlier years: 1920 $0.15 0.13 0.12 0.13 0.13 1925 0.13 26 0.13 27 0.13 28 0.13 0.13 29 1930 0.12 31 0.11 32 0.10 33 0.09 34 0.10 1935 0.10 36 0.10 0.11 37 38 0.10 39 0.10 1940 0.10 41 0.11 42 0.12 43 0.13 44 0.13 1945 0.13 46 0.14 47 0.16 48 0.18 49 0.17 1950 0.18 51 0.19 52 0.20 53 0.20 54 0.20 1955 0.20 56 0.20 57 0.21 58 0.21 59 0.21 1960 0.22 61 0.22 62 0.22 63 0.23 64 0.23 1965 0.23 66 0.24 0.25 67 68 0.26 69 0.27 1970 0.29 0.30 71 0.31 72 73 0.33 74 0.36 1975 0.40 76 0.42 0.45 77 78 0.48 0.53 79 0.61 1980 81 0.67 82 0.71 0.73 83 0.76 84 1985 0.79 0.81 86 0.84 87 0.87 88 0.91 89 0.96 1990 1.00 91 21 22 23 24 $2.94 2.63 2.46 2.51 2.52 2.58 2.60 2.55 2.52 2.52 2.45 2.23 2.01 1.90 1.97 2.02 2.04 2.11 2.07 2.05 2.06 2.16 2.40 2.54 2.59 2.65 2.87 3.28 3.53 3.50 3.54 3.82 3.91 3.94 3.95 3.94 4.00 4.13 4.25 4.28 4.35 4.40 4.45 4.51 4.56 4.64 4.78 4.91 5.11 5.39 5.71 5.95 6.15 6.53 7.25 7.91 8.37 8.91 9.59 10.67 12.11 13.37 14.19 14.65 15.27 15.81 16.12 16.71 17.39 18.22 19.21 20.00 $74 66 62 63 63 65 65 64 63 63 61 56 50 47 49 50 51 53 52 51 52 54 60 64 65 66 72 82 88 87 88 95 98 98 99 99 100 103 106 107 109 110 111 113 114 116 119 123 128 135 $147 143 149 154 163 181 285 298 307 327 362 198 209 223 240 267 396 418 445 480 533 303 334 355 366 382 395 418 435 456 606 668 709 732 763 791 806 835 869 911 480 500 1,000 403 131 123 125 126 129 130 128 126 126 123 112 100 95 98 101 102 106 104 102 103 108 120 127 129 132 143 164 177 175 177 191 195 197 198 197 200 207 212 214 217 220 222 225 228 232 239 245 256 269 960 tected by "inflation hedges" (including "safe" Government bonds) will be severe. In the meantime, as illustrated in the accompanying tables, even if the recent trend of "moderate" price inflation persists for some time the effect on the buying power of the dollar will be substantial. And chronic uncertainty over what the dollar will be worth in the future will continue to confound attempts at long-range financial planning. CHANGES IN THE PURCHASING POWER OF THE DOLLAR SINCE 1920 The two tables on this page illustrate the impact of price inflation on the purchasing power of the dollar over the past 70 years. The figures are based on the Consumer Price Index, a statistical measure that is imperfect but is widely viewed by economists as the best available approximation of the "cost of living." Table A shows dollar amounts for each year since 1920 that had the same buying power as one dollar, $20, $500, and $1,000 in 1991. In other words, how much you would have needed in earlier years to buy what one dollar, $20, etc. bought in 1991. For example, in 1975 you needed only 40 cents to buy what one dollar could buy in 1991. You needed only $7.91 to buy what $20 buys today. Because the general price level was less than half what it is today, far fewer dollars were needed to purchase the same amount of goods and services. In 1945, when prices were even lower, a mere 13 cents had the same buying power as a dollar in 1991, and $132 had the buying power of today's $1,000. Thus, in terms of the goods and services it could purchase, the 1945 equivalent of today's $20,000 salary was $2,640 (20 × $132). Table B illustrates the shrinkage in the dollar's buying power somewhat differently. It shows the equivalent purchasing power in 1991 of one dollar, $5, $20, and $1,000 in each year since 1920. In other words, how much currency one needs today to match the buying power that these amounts had in earlier years. For example, to match the buying power that one dollar provided in 1975 you would need $2.53 today. To match the buying power that a dollar had in 1945 you would need $7.56. The first column in Table B essentially shows how much general prices have increased over the years. Since 1945, for example, prices have increased more than seven times (7.56 times, to be more precise). Just since 1987 prices have increased 20 percent, and it now takes $1.20 to match the buying power that one dollar had 4 years ago. 2 Table B YESTERDAY'S DOLLARS $ 20 !% 500 $1,000 $1 and their equivalent purchasing power today: $6.79 $135.83 7.62 152.34 22 8.12 162.35 159.49 23 7.97 7.94 24 158.87 1925 154.94 7.75 26 7.69 153.77 7.84 156.73 27 28 7.93 158.56 29 7.93 158.56 163.00 1930 8.15 31 8.96 179.12 32 9.96 199.27 33 10.53 210.59 34 10.16 203.24 1935 9.91 198.30 36 9.82 196.39 37 9.48 189.53 38 9.66 193.13 39 195.44 9.77 1940 9.70 194.05 41 9.24 184.81 42 8.35 167.01 43 7.87 157.34 44 7.73 154.65 1945 7.56 151.21 46 6.98 139.55 47 6.09 121.82 48 5.66 113.19 49 5.72 114.31 1950 5.65 113.04 5.24 51 104.76 52 5.12 102.39 53 5.08 101.62 54 5.06 101.24 1955 5.07 101.49 56 5.00 100.00 4.84 57 96.79 58 4.71 94.22 59 4.67 93.36 1960 4.60 91.99 61 4.55 90.96 62 4.50 89.96 63 4.44 88.78 64 4.38 87.63 1965 4.31 86.24 66 4.19 83.76 67 4.07 81.50 68 3.91 78.21 69 3.71 74.23 1970 3.50 70.08 71 3.36 67.19 72 3.25 65.04 73 3.06 61.23 74 2.76 55.18 1975 2.53 50.56 76 2.39 47.80 77 2.25 44.90 78 2.09 41.71 79 1.87 37.49 1980 1.65 33.02 81 1.50 29.92 82 28.19 1.41 83 1.37 27.31 84 1.31 26.20 1985 1.26 25.29 86 1.24 24.82 87 1.20 23.94 88 23.00 1.15 89 21.95 1.10 1990 1.04 20.82 91 1.00 20.00 1920 21 $3,396 $6,792 3,808 7,617 4,059 8,118 3,987 7,975 3,972 7,943 3,874 7,747 3,844 7,689 3,918 7,837 3,964 7,928 3,964 7,928 4,075 8,150 4,478 8,956 4,982 9,963 5,265 10,530 5,081 10,162 4,957 9,915 4,910 9,819 4,738 9,477 4,828 9,656 4,886 9,772 4,851 9,702 4,620 9,240 4,175 8,350 3,933 7,867 3,866 7,732 3,780 7,560 3,489 6,978 3,046 6,091 2,830 5,660 2,858 5,715 2,826 5,652 2,619 5,238 2,560 5,119 2,541 5,081 2,531 5,062 2,537 5,075 2,500 5,000 2,420 4,840 2,355 4,711 2,334 4,668 2,300 4,599 2,274 4,548 2,249 4,498 2,219 4,439 2,191 4,382 2,156 4,312 2,094 4,188 2,037 4,075 1,955 3,911 1,856 3,711 1,752 3,504 1,680 3,359 1,626 3,252 1,531 3,062 1,379 2,759 1,264 2,528 1,195 2,390 1,123 2,245 1,043 2,085 937 1,874 826 1,651 748 1,496 705 1,410 683 1,366 655 1,310 632 1,265 620 1,241 599 1,197 575 1,150 549 1,097 521 1,041 500 1,000 Both tables make clear the impact of price inflation on fixed-dollar incomes. For example, suppose you retired in 1977 with a fixed company pension of $1,000 per month. By 1991, that $1,000 no longer bought the same amount of goods and services that it did when you retired. In fact, $1,000 in 1991 bought only what $445 would have purchased in 1977 (see Table A). This drop in the purchasing power of your pension is the same as it would be if prices had remained steady but the company had cut your pension to $445. Actually, the prices of goods and services more than doubled — and to match the purchasing power that your $1,000 pension provided in 1977 it would have to be $2,245 in 1991 (see Table B). On the other hand, the tables also show how debtors may benefit from price inflation. Suppose you borrowed $1,000 in 1985 and immediately spent it on goods and services. If you repaid the principal in 1991, your $1,000 payment effectively "cost" you, in terms of goods and services forsaken to repay the debt, less than $1,000, because of the 26 percent increase in general prices since 1985. In fact, your $1,000 payment is the equivalent of only $791 in 1985 dollars (see Table A). To repay the same purchasing power that you borrowed 6 years earlier, your payment in 1991 should be $1,265 (see Table B). Of course, the debtor's gain is the creditor's loss. After adjusting for price WHAT YOUR DOLLARS WILL BE WORTH if the price changes over the next 30 years match i the annual changes from1961-91. ' Year $1 1991 1.00 0.99 0.98 0.96 0.95 0.92 0.90 0.86 0.82 0.77 0.74 0.72 0.67 0.61 0.56 0.53 0.49 0.46 0.41 0.36 0.33 0.31 0.30 0.29 0.28 0.27 0.26 0.25 0.24 0.23 0.22 92 93 94 95 1996 97 98 99 2000 01 02 03 04 2005 06 07 08 09 2010 11 12 13 14 2015 16 17 18 19 2020 21 $20 20.00 19.78 19.52 19.27 18.96 18.42 17.92 17.20 16.32 15.41 14.77 14.30 13.46 12.13 11.12 10.51 9.87 9.17 8.24 7.26 6.58 6.20 6.01 5.76 5.56 5.46 5.26 5.06 4.83 4.58 4.40 $500 500 495 488 482 474 460 448 430 408 385 369 358 337 303 278 263 $1,000 1,000 989 976 963 948 921 896 860 816 770 739 715 229 206 182 164 155 673 607 556 526 494 459 412 363 329 310 150 300 144 288 139 136 278 247 273 263 132 126 121 253 114 110 229 220 241 PURCHASING POWER OF THE DOLLAR, 1920=100 200.0 100.0 50.0 - 25.0 - 12.5 1920 '25 inflation the lender is effectively getting years of the 1980's, and shows no sign back only $791 of the $1,000 he lent. of stopping. (Theoretically, the lender could offset his loss on the principal by charging a rate WHAT WILL THE DOLLAR of interest sufficiently higher than the BE WORTH IN THE FUTURE? rate of price inflation, but the difficulty is in accurately forecasting what that rate The record of past price inflation is will be.) clear. What about the prospects for the The extent to which gains on assets reflect generally rising prices rather than W H A T THE PRICE LEVEL WILL BE real income also is clear. Take the case if the trend from 1961-9 r is repeated in 1991-2021 . of an investor who bought a share of stock in 1979 for $12 and sold it in 1991 Year $20 $500 $1,000 $1 for $50. His nominal capital gain is $38 1991 1.00 20.00 500 1,000 ($50 - $12). As shown in Table B, how92 506 20.22 1,011 1.01 93 1.02 20.49 512 1,025 ever, between 1979 and 1991 the general 94 1.04 20.76 519 1,038 price level increased 87 percent, and one 95 1.05 21.09 1,055 527 needed $1.87 to match the buying power 1996 1.09 543 1,086 21.72 that one dollar had in 1979. Adjusting 97 1.12 22.32 558 1,116 the original stock price for this price in98 1.16 581 23.26 1,163 flation gives a value of $22.44 99 24.51 1.23 613 1,225 ($12 × 1.87), and thus the real income 2000 1.30 25.96 649 1,298 gain is not $38 but $27.56 ($50 - $22.44). 01 1.35 27.08 677 1,354 Under current U.S. law nominal capi02 1.40 27.97 699 1,398 03 1.49 29.71 743 1,486 tal gains are fully taxable as income, even 04 1.65 32.97 824 1,648 though they may not represent real in2005 900 1.80 35.98 1,799 come. (In the example above, the inves06 951 1.90 38.06 1,903 tor would owe income tax on $38, even 07 2.03 40.51 1 ,013 2,026 though his real income was only $27.56.) 08 2.18 43.62 1 ,090 2,181 This system is both unfair and ineffi09 48.53 1 ,213 2,426 2.43 cient, in that it encourages people to hold 2010 2.75 55.09 1 ,377 2,754 stocks they would otherwise sell, in or11 3.04 60.80 1 ,520 3,040 12 3.23 64.53 1 ,613 3,227 der to avoid paying taxes on nominal 13 66.61 1 ,665 3,330 3.33 gains. In this respect, it would be prefer14 3.47 69.44 1 ,736 3,472 able to index capital gains for price in2015 3.60 3,596 71.92 1 ,798 flation. 76 3.67 73.30 1 ,833 3,665 The accompanying chart shows the 17 3.80 75.98 1 ,900 3,799 same information represented in Tables 18 3,954 3.95 79.08 1 ,977 A and B. The continuous downtrend in 19 4.14 82.88 :>,O72 4,144 the purchasing power of the dollar is ap2020 87.37 ;>,184 4,368 4.37 4,548 21 90.96 I>,274 4.55 parent, even during the "low inflation" 3 THE PURCHASING POWER OF THE DOLLAR IN FUTURE YEARS AT VARIOUS RATES OF PRICE INFLATION Years '98 '99 2000 '01 '94 '95 '96 '97 '93 Rate 1992 '02 3% $.97 $.94 $.92 $.89 $.86 $.84 $.81 $.79 S.77 $.74 $.72 .70 .68 .65 .79 .76 .73 .85 .82 .92 .89 4% .96 .61 .58 .68 .64 .75 .71 .86 .82 .78 5% .95 .91 .53 .59 .56 .75 .70 .63 .84 .79 .67 .94 .89 6% .54 .51 .48 .58 .76 .62 .82 .71 .67 7% .93 .87 .54 .50 .46 .43 .68 .63 .58 .86 .79 .74 8% .93 .46 .42 .39 .55 .50 .84 .65 .60 .92 .71 9% .77 .42 .39 .35 .56 .51 .47 .83 .75 .68 .62 10% .91 11% .90 .81 .73 .66 .59 .53 .48 .43 .39 .35 12% .89 .80 .71 .64 .57 .51 .45 .40 .36 .32 future? What will the dollar be worth 5,10, or 15 years from now? What will it be worth when you retire, or when your children graduate from school? If history repeats itself and the dollar loses value at the same rate over, say, the next 30 years that it did over the past 30 years, the outlook is bleak indeed. The two tables on page 3 illustrate this scenario; they assume that the year-to-year changes in the CPI over the period 1991-2021 will match exactíy the changes recorded during 1961-1991. If this were to happen, the purchasing power of today's dollar could be expected to drop to 74 cents over the next 10 years (see table on left). A basket of goods and services that costs $1,000 today would cost $1,354 in 2001. Twenty years from now, in 2011, the dollar would be worth just 33 cents — and you would need over $3,000 to buy what $1,000 buys today (see table on right). It is very unlikely, of course, that the future price trend will exacüy replicate that of the past. Nevertheless, the illustration is instructive, since the period 1961-91 covers a wide range of annual changes in the general price level, from the 2 percent increases of the 1960's to the "double digit" in- '06 '07 '10 '11 '12 '04 '05 '08 '09 '03 $.70 $.68 $.66 $.64 $.62 $.61 $.59 $.57 $.55 $.54 .46 .44 .58 .56 .53 .51 .49 .47 .62 .60 .38 .36 .51 .48 .46 .44 .42 .40 .56 .53 .31 .44 .42 .39 .35 .33 .29 .50 .37 .47 .26 .24 .41 .39 .36 .34 .32 .30 .28 .44 .34 .23 .21 .20 .40 .32 .29 .27 .25 .37 .16 .30 .25 .23 .21 .19 .18 .36 .33 .27 .24 .14 .29 .26 .22 .20 .18 .16 .15 .32 .29 .26 .23 .21 .19 .32 .17 .15 .14 .12 .11 .29 .26 .23 .20 .18 .16 .15 .09 .13 .12 .10 crease of the late 1970's, to the "disinflation" of mid-1980's. The projections for the next 10 years, it should be noted, are based on the "good old days" of the l96O*s, when the average annual rate of price inflation was only 3.1 percent. At that rate, the purchasing power of the dollar would drop a full 25 cents by 2001. The table on this page shows what the buying power of today's dollar would be over the next 20 years at various assumed rates of price inflation. If the rate at which the dollar loses value remains a "moderate" 3 percent —and given recent experience, this would seem to be a "lowball" long-term forecast — it still will be worth only 64 cents by the time the first "baby boomers" turn 60 (in 2006). In 20 years its buying power would be cut almost in half. On the other hand, if price inflation accelerates, today's dollar could be worth much less. Unfortunately, there is no way to forecast accurately which trend will prevail. In our view, however, as long as politicians face pressures to debase the currency and there is nothing to prevent them from doing so, the possibility of a reacceleration in price inflation remains a serious threat. Economic Education Bulletin (ISSN 0424-2769) (USPS 167-360) is published once a month at Great Banington, Massachusetts, by American Institute for Economic Research, a scientific and educational organization with no stockholders, chartered under Chapter 180 of the General Laws of Massachusetts. Second class postage paid at Great Bamngton, Massachusetts. Printed in the United States of America. Subscription: $25 per year. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Economic Education Bulletin, American Institute for Economic Research, Great Bamngton, Massachusetts 01230. ECONOMIC EDUCATION BULLETIN AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH Great Barrington, Massachusetts 01230 RETURN POSTAGE GUARANTEED Second class postage paid at Great Barrington, Massachusetts