Transparency Coffee Supply Chain

advertisement

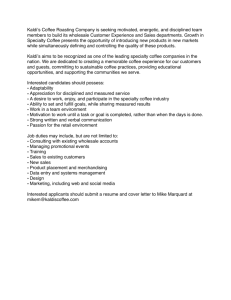

T he Long Pi pe Transparency and the Coffee Supply Chain by Hanna Neuschwander I f you were to place a coffee grower at one end of a pipe pointed in the direction of your kitchen, he or she would be hard pressed to peer through it and discern the tiny vision of you, morning cup in your hand, on the other end. It would be equally difficult for you, squinting with sleep in your eyes, to make out a distant, weathered face on the green slopes of a coffee farm. continued on page 24 Finca El Divisadero near Ataco, El Salvador, May 2012 | photo by Bruce Mullins 22 roast J a n u a r y | F e b r u a r y 2 0 13 23 The Long Pipe | Transparency (continued) Sure, it’s a long way from one place to the other. But the pipe doesn’t just cover a lot of distance. It’s kinked, bent in all sorts of tortuous ways, each bend one more place where coffee changes hands and where information about it must turn a corner or become pinched off altogether. That’s assuming you can collect information well enough to direct a stream into the pipe to begin with. Even then, all that might come out the other end is a dribble. Given the complex global supply chain for coffee, it’s unsurprising that information has not flowed freely, when it has flowed at all. Coffee growers, in particular, have been left out of conversations about where their coffee goes after it leaves the farm. It simply disappears. “This is not an industry that has a long history with benevolence and transparency,” says Monika Firl, What is Transparency? At its most basic, transparency is the act of making information available. This could include purchase prices for green coffee, the number of years a roaster has had a relationship with a particular farm, or the salaries it pays its baristas. Transparency underpins producer relations manager at the importing collective Cooperative a concept of business relations that emphasizes Coffees. fairness and mutual responsibility. And it’s more But advances in connecting one end of the coffee chain to the other—growers to roasters, and all the roles in between—have been a critical element to the success of specialty coffee over the last two popular than ever, given concerns about health, safety, environmental standards, ethics and labor. decades. Today it’s possible, in ways that are both nuanced and immediate, to “see through” the pipe, to use this transparency for continuous improvement, and to hold each end accountable for its practices. Change has come relatively rapidly. Kim Elena Ionescu, coffee buyer and sustainability manager at Counter Culture Coffee, recalls a moment in 2005 when Counter Culture founder and president Brett Smith shared a breakdown of the company’s costs to roast, prepare, and sell coffee for a room full of other roasters as well as coffee growers at the Let’s Talk Coffee conference hosted by Sustainable Harvest Coffee Importers. “It seemed revolutionary to share that information,” she says. “Given where we are now, it seems almost quaint.” Consider the leap from that presentation to the 2012 launch of WebMap 2.0, an online traceability/transparency tool created by Brazil-based green coffee exporter NuCoffee. Through View of coffee field in Matas de Minas, Brazil. | photo courtesy of NuCoffee WebMap, roasters can browse from a selection of coffees (the tool encompasses more than 1,400 individual farms and 20 co-ops in Brazil) based on region, cooperative name, type of processing, cupping score and flavor profiles. Farm profiles contain data ranging from the number of employees and families working on the farm, to predominant flora and fauna, to altitude and weather information. When a roaster buys a lot, NuCoffee provides additional resources that range from tracking processing information to the ability to generate QR (quick response) codes that lead customers to a customizable coffee biography. Smaller farms benefit from systematized collection of data that helps identify or improve quality potential, and larger farms benefit from the ability to collect sophisticated, geographically referenced Technicians arrive at a farm in South of Minas, Brazil, to train producers on implementing NuCoffee’s traceability system. | photo courtesy of NuCoffee 24 roast continued on page 26 J a n u a r y | F e b r u a r y 2 0 13 25 The Long Pipe | Transparency and the Coffee Supply Chain (continued) data that help them develop strategies to manage variables platforms support shifts that are fundamentally cultural in nature. ranging from planting to fertilization to harvesting. “The industry has shown significant progress in promoting more A similar but potentially more expansive tool is C-sar. marketing manager. “We notice an increasing commitment to op to log a huge variety of data including coffee varietal, acknowledging coffee producers. This is an important step to help growing altitude, pest control, pruning and harvesting producers leave anonymity.” practices, agricultural inputs and other soil information, 26 roast Transparency has gained traction as more attention is focused processing methods, carbon footprint, labor conditions, on sustainable business partnerships and the value for producers. and farm stories including pictures and videos. Farmers and Third-party certification systems, like those offered by USDA Organic associations collect their own data using the tool and then and Fair Trade USA, have incorporated at least limited transparency choose how to make the data available to roasters (as well as requirements from the beginning, though usually around a narrow others in the supply chain). There is also a roaster module, set of parameters. Transparency has become especially important for which roasters can use to track a large variety of quality roasters interested in pursuing long-term trading relationships with control data, and they can likewise share their information farms under the direct or relationship model. with importers, exporters and growers. Cropster, the social Drying coffee at Fazenda dos Tachos, South of Minas, Brazil. The farm uses NuCoffee’s traceability system to help better segment coffee varietals and quality potential for specialty coffee production. | photo by Daniel Friedlander transparent business relations,” says Daniel Friedlander, NuCoffee’s This software provides a platform for any producer or co- Randal Ribeiro, a NuCoffee quality specialist, meets with producer Gilmar Barbosa to implement best farming practices at farm Penedo II. Processes are recorded in WebMap 2.0 and tracked by the producer or by coffee roasters, enabling them to provide feedback to the producer. | photo courtesy of NuCoffee As a business proposition, transparency is about sharing entrepreneurship company that developed C-sar, has clients information, understanding each other’s costs of production, and own costs to run the business risk putting themselves in a precarious in more than 20 countries and there are so far more than making sure everyone is clear on what is being asked for and delivered. financial position. 20,000 farms registered in the C-sar system. Because of the Many roasters now use transparency contracts, which allow each potential it holds for connecting growers with roasters in member of the coffee chain to see what the others are being paid— with uncertainty about the best path forward. Some roasters are deeply transparent ways, it was named the best new product everyone knows the value being ascribed to his or her services. By eager to explore ways to deepen transparent business relationships in the “equipment for origin” category of the Specialty Coffee forcing clarity around pricing, transparency also generally exposes with their trading partners while also inviting customers in on Association of America’s (SCAA) annual awards in 2012. situations where prices are failing to cover costs. This can be true the conversation. Others grapple with the question of how much either at the farm or at the cafe. Cafes that set their prices according information consumers actually want about their coffee. Technology has enabled change to happen rapidly and to scale up quickly in the last few years. But these online to what neighboring businesses charge rather than based on their The advance of transparency in recent years may leave roasters continued on page 28 J a n u a r y | F e b r u a r y 2 0 13 27 The Long Pipe | Transparency and the Coffee Supply Chain (continued) THE experts weigh in For roasters interested in pursuing transparency, the experts weigh in with advice. “A common misunderstanding is to think customers will care about every single detail of coffee traceability, and of course they will not,” says Friedlander. For most, the mere nugget of a story about a farm or a farmer—a name on a bag of beans, for example—is enough to satisfy any curiosity a coffee drinker has about where his coffee comes from. Even so, some roasters see transparency— On working with your importer supply side and public facing—as essential to the future of their business. These roasters are putting more effort into Daniel Friedlander, NuCoffee making the relatively new transparency of the commodity “If you are a roaster who doesn’t have significant control over producer relations (e.g. you chain accessible for customers. buy on spot and not through the direct-trade or relationship model), then the first place to begin is with your importer. Ask questions: Do they make traceability information easy to access and use? How was the data gathered and verified? Was it independently audited? “ It can be tricky to talk about transparency because of the one thing it’s most often confused with: traceability. Knowing down to a fairly narrow level of detail where coffee comes from—granular origin data—is a precursor On producer relations to thorough transparency. Friedlander believes the two should be deeply interdependent and spoke about the Daniel Friedlander, NuCoffee topic at the 2012 SCAA Symposium. There, he lamented “If you want to partner with producers and are looking for consistency in flavor profiles, that all too often traceability and transparency are not you need to know each individual farm and producer. You may need to know details ranging connected. “Knowing the origin of a coffee doesn’t mean from milling to warehousing to shipping so that if a problem happens, you can locate the you have any kind of connection with the producer. cause and provide accurate feedback.” Matt Earley, Just Coffee “The company’s most significant transparency cost is one we would incur regardless: maintaining relationships with coffee producers through travel and documenting the visits through blog posts.” Monika Firl, Cooperative Coffees “For us, an importer, the biggest transparency tool we have is our luggage. Face-to-face meetings are critical, even though they don’t tell you everything.“ On data gathering and infrastructure Kim Elena Ionescu, Counter Culture Coffee “Traceability takes a commitment to starting to measure data, and then measuring them. It really doesn’t have to be that resource intensive. Our direct trade report doesn’t cover every coffee we purchase. You can start with one coffee or two coffees. It may feel random the first year, but after time some things come together.” View of a coffee plantation in South of Minas, Brazil. photo courtesy of NuCoffee Commodity coffee can have traceability,” he said at Daniel Friedlander, NuCoffee Symposium. But the inverse is just as problematic—a “Transparency is more than pinpointing locations along the coffee chain. When farmer may have meticulous agricultural practices and transparency becomes a structured platform for tracing processes, growers can improve a roaster may have made significant contributions to, quality and replicate successes on a larger scale, while co-ops, mills and warehouses can say, environmental stewardship on a farm. Yet without optimize logistics, and roasters can reduce risks while gaining the ability to provide more the record keeping that traceability requires, “it may be information to their customers.” perceived as propaganda.” Atlas Coffee Importers founder Craig Holt agrees: “You really have to be careful about Matt Earley, Just Coffee overselling what it is that we’re doing. We overstate the “I don’t really think there are a lot of challenges to pursuing transparency, which is why I’m degree to which we help people. We overstate the quality baffled that more people don’t do it. One challenge to transparency reporting for us was the time expense of setting up the transparency website, which was done in collaboration with Cooperative Coffees. We did spend a lot of time to get it up and running. But once that was done, the data entry part hasn’t been very costly. Once you invest in the main system, it’s just not that hard. There’s not a lot of downside or work to doing it.” of the coffee we’re producing. We overstate the benefits to the environment. It’s almost like sustainability porn the way people talk about what they do, the changes they make. You need to be able to back that up with vivid traceability and transparency.” continued on page 30 28 roast J a n u a r y | F e b r u a r y 2 0 13 29 The Long Pipe | Transparency and the Coffee Supply Chain (continued) Neither concept is sustainable on its own, Friedlander suggests. “Let’s not forget that full time now, and his coffees are carried in a number traceability is not just about sharing stories,” he notes. “There’s value in better supply chain of highly regarded cafes). Barany still says he believes management and also from helping producers to replicate on a larger scale what worked well transparency should be a driving force in every business, in coffee quality.” While the coffee industry has an insatiable appetite for traceability at the but he notes that, “there may be better ways to share moment, farmers are looking for transparency and better overall communication. information with people than our original transparency The emphasis on transparency is also growing outside the world of coffee, and this report.” In particular, he feels there is probably a better may eventually exert significant pressure on the industry as a whole to catch up in its way to be tactful with farmers. “Pricing in Brazil and transparency efforts. Companies like Wal-Mart are playing with new technologies, including Panama is just different. But I can guarantee you that radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags, to embed origin information, including details the Brazilian farmer will be looking at the Panama about health and safety, in products ranging from jewelry to paper cups. For all companies, farmer’s asking price and wondering why they aren’t the big question is how much data to collect and make available, and in what degree of detail. getting the same price.” And this is where roasters committed to transparency differ greatly. Jen St. Hillaire is also a microroaster with her own company, Scarlet City Coffee Roasters in Oakland, Challenges for Small Roasters When I first encountered Kuma Coffee, a microroaster in Seattle, it was barely a company. The owner, Mark Barany, began as a hobby roaster while working full time in the IT department at Seattle Pacific University. He did everything for his tiny operation himself— down to filling bags of coffee and stamping the Kuma logo on them by hand. But he did one other thing that was unusual, especially for a roaster of his size: He published green coffee purchase prices on his website. The information was basic—just the name of either the farm or the importer from which the coffee was purchased, as well as the price per pound. Barany emphasizes that simply publishing purchasing data was easy—it was a matter of uploading information he already had on file. “I want my business to be honest and transparent,” he says. “I want my customers to have complete confidence that we are buying world-class coffees and paying healthy premiums Calif. She has likewise flirted with basic transparency reporting such as Kuma’s but decided that simply posting purchasing prices isn’t a meaningful indicator for customers. St. Hillaire points out that pricing can depend on many factors, including the amount of coffee purchased, the season, whether it’s organic or fair-trade certified, and the timing of contracts. A roaster who purchases coffee pegged to the “C” market will pay a higher price if they book right before a “C” market price drop than a roaster who books after the drop, for the same coffee. “Where exactly is the transparency in this, Quality specialists work closely with producers on traceability projects. photos courtesy of NuCoffee and what is the point of it if you don’t have something tangible to compare it to?” says St. Hillaire. “If you’re just throwing numbers out there with no reference to anything else, what does it mean?” to our farmers.” Nevertheless, Barany says he received limited feedback from his customers about this transparency initiative, even though local media paid attention. According to Barany, it was mostly farmers who took notice: “At least a couple of our partnering farmers were checking out the list to see what prices we were paying to other direct-trade partners.” It was this, in part, that led Barany to stop publishing the information in 2012. “One of How Much Information Is Too Much? In contrast, perhaps the most complete transparency project a coffee roaster has taken up our partners was upset that we were buying another neighboring farm’s coffee at a higher in the United States is from a mid-sized regional roaster in the Midwest called Just Coffee, a price and wanted to use the data as leverage, even though his coffee didn’t cup out quite as member of Cooperative Coffees. It begins when Cooperative Coffees posts all of the contracts, nice.” Barany says that supplying “bonus” content such as a transparency report has taken a invoices and bills of lading for every lot of coffee it imports. The roaster members of the co-op back seat to keeping up with new business and improving offerings and service (he is roasting can assign a code to their coffees that links back to this paperwork via a website. Just Coffee has done more with that available data than any of the other co-op members. Early on, Just Coffee printed basic data about each coffee right on the coffee bags, along with a code that led customers to a website where they could access nearly all of the purchasing documents for a given lot. The bag label included a breakdown of how much of the customer’s per-pound price went to the farmer, as well as to import fees. It also included a generic breakdown of labor costs, label and bag costs, and markup. It goes without saying that to be truly transparent, you have to be accurate—but that isn’t always easy in the coffee business. When green coffee pricing is determined by a floating premium over the “C” market cost, the actual amount paid to a farmer may differ from the forward contract price because of daily (even hourly) “C” market fluctuations. Just Coffee has removed its financial transparency label from printed bags because of this uncertainty. Instead, a new generation of bags will include links allowing customers to access real-time data as well as purchasing documents online. Just Coffee co-founder and farmer relations/outreach coordinator Matt Earley thinks people appreciate being given a chance to make thoughtful choices. “From a marketing perspective, we believe it sets us apart and that people come to us for this reason,” says Earley. “We look at business as a way to create a better model within an industry that needed a better View of a coffee plantation in South of Minas, Brazil. Traceability systems help producers in different regions maximize quality and yield. | photo courtesy of NuCoffee 30 roast model.” continued on page 32 J a n u a r y | F e b r u a r y 2 0 13 31 The Long Pipe | Transparency and the Coffee Supply Chain (continued) information they would like reported. “People information is too much for them, growers get better at that, we put a (CBI) produces a transparency report that’s Thornton, “with the intent to try and inspire are comparatively well versed in the like to see that it’s there,” he says. But he adds rather than proactively keeping difficult value on it,” Ionescu says. Counter directly modeled on the one developed by others to follow a similar path.” politics of trade. (They are also generally that most “probably only experiment with it documents inaccessible. Culture is especially interested in what Counter Culture. The company uses it to motivated by cooperativism—Just Coffee once to see how it works; only a handful of it indicates if growers don’t know report on all of its Project Direct line of game. For coffee verified to meet their Coffee is one of the top-selling coffee brands in customers check back constantly.” their costs. “If you don’t know how coffees—and because of CBI’s scale, those and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) Practices much you’re spending on your farm, coffees are reaching a large audience standards, the company says financial you’ll never really be able to answer (customers include Target; coffees are sold transparency “down to the farmworker level” the question of what the right price under the Archer Farms label). is a must. Demonstrating that money goes It helps that Just Coffee’s customers food co-ops nationally.) Earley says that Despite Earley’s assurances that Just Just Coffee receives regular inquiries about Coffee’s customers do make use of the the information they provide, including generous data they provide, the data can be from customers who spot mistakes or difficult to navigate. Earley is comfortable make recommendations about additional letting his customers decide how much Curating Transparency Counter Culture Coffee’s Ionescu is blunt about it: “No one reads the transparency scorecard. We get zero questions about it.” Even so, Counter Culture has made the report a centerpiece effort for the company. Counter Culture is one of the only coffee companies in the United States that produces an annual transparency report—one that curates complex data for customers so that it’s digestible while still being meaningful. The report has evolved from a simple willingness to share information to a more concerted effort to push it into the public sphere. In 2007 and 2008, Counter Culture published a minimum green coffee purchase price—their first foray into financial transparency. The first full report was published in 2009, with information garnered from an annual audit, including price, most recent farm visit, and cupping score. The company also includes duration of the farm relationship because, according to Ionescu, “that’s an area where I think our work, and philosophical approach to direct trade, differs from some of our peers.” For the 2012 report, Ionescu wants to up the ante, redesigning it to inspire more interest. “There’s still so much to be done to engage consumers,” she says. In an age of information overload, the company believes that telling a simple and visual—but detailed and accurate— story is crucial. The 2012 report will be combined with other data the company collects in a formerly separate sustainability scorecard. Items such as whether or not each farm documents how much it costs to produce a harvest will also be included. Most estate farms collect this data routinely, but that’s not true of smallholders. “If a co-op has a program in place to help their 32 roast is for the coffee. It’s not a good price for any grower if it doesn’t cover cost “We took this approach to try and create a consistency,” says CBI’s roastmaster Paul Even Starbucks has skin in the transparency where it is supposed to go is a prerequisite for continued on page 34 of production,” she adds. “But if we’re paying $5 a pound and it’s not covering production costs, there’s something wrong on that farm.” The company wants to see its wholesale clients apply the same logic to their menu pricing. Rather than simply looking at what the chain coffeehouse across the street charges, they encourage clients to look at their real costs and to price drinks accordingly. Ionescu emphasizes that it’s critical in healthy, long-term business relationships for growers to understand why their coffee costs $15 per pound retail in the United States, when they were paid $4. “I go to co-ops all the time and present our cost of production in the same format we’d use to talk to shareholders”—which usually means showing them a spreadsheet full of numbers. “We need to make it more interesting and engaging for them.” In part because of the effort Counter Culture invests in communicating with farmers, Ionescu reports the company hasn’t faced any resistance from growers to publishing purchase prices. “I have heard from other roasters that they don’t want to share FOB (free on board) prices because it’s like publishing a farmer’s salary, but that hasn’t been my experience.” After initial resistance from some of the company’s importing partners, who Ionescu believes were concerned about being cut out of the supply chain, everyone eventually came around. “We worked hard to keep up open and honest communication with everyone.” Other coffee companies have taken notice and are extending the concept. Coffee Bean International J a n u a r y | F e b r u a r y 2 0 13 33 The Long Pipe | Transparency and the Coffee Supply Chain (continued) any coffee to be verified. “It’s a nonstarter if this isn’t happening,” says Jim Hanna, director of environmental impact. “We’ve had the transparency requirement since day one of C.A.F.E.” Starbucks also has a sophisticated set of “global responsibility” reports on everything from fair trade purchasing to in-store water consumption, which take to heart the lessons of consumer-facing, modern information design. The scorecard, a sort of executive summary of the full report, is remarkably easy to digest. Some of that digestibility comes at the expense of detail. The furthest Starbucks goes in disclosing financial information is to give an average purchase price for their green coffee ($2.38 per pound in 2011); they don’t report about individual purchases. Hanna says that—similar to Counter Culture—not many people read the scorecard by itself. “If you have standalone CSR [corporate social responsibility] reports, only a limited group of people will read them—academics, activists, employees and competitors, usually. Technicians arrive at a farm in South of Minas, Brazil, to train producers on implementing NuCoffee’s WebMap traceability system. | photo courtesy of NuCoffee But as we’ve embedded the stories in the larger messages, it becomes relevant for customers,” Hanna adds. For that reason, there is a prominent “Responsibility” web page linked from the Starbucks homepage that contains much of the scorecard information. “Our company is built on our relationships and the trust our customers have for us,” Hanna says. “There is a sort of natural cynicism about multinationals and large brands with the ‘just trust us’ message. So things do need to be externally verified. Trust drives people to come back to our store. And this kind of reporting engenders trust.” demands, not just react to them. And of course, it can still be in the long-term best interest of companies to be transparent, even if consumers don’t express that view themselves. On the contrary, it’s empowering for both coffee drinkers and producers to be able to conjure the idea of one another—to “see,” metaphorically at least, from one end of the pipe to the other. As technology and culture shift, information about coffee will travel not only a straighter path, but a wider one. Should Consumers or Roasters Drive the Transparency Train? No one I spoke with argued that increasing transparency for the purposes of improving relationships in the supply chain was a bad idea. (Though the value is broadly accepted, it should be noted that Hanna Neuschwander is a freelance writer who is continuously amazed by coffee’s ability to pull her deeper into its orbit. She is the managing editor of an open-access scholarly journal, Democracy & Education, and the author of Left Coast Roast (Timber Press, 2012), a guidebook to artisan and iconic coffee roasters from Seattle to San Francisco. still only a fraction of transactions are performed transparently.) But feelings were more mixed when it came to how that transparency could be extended or explained for consumers, who appear to be largely unmotivated by the details. Ionescu believes that most of Counter Culture’s customers appreciate that the transparency report exists but don’t bother to read it, seek out details or ask questions. “Frankly, it makes it incredibly easy to take advantage of consumers, especially in the direct trade model,” she says. “There are so many definitions, r e s ou rc e s Tools Cropster C-sar www.cropster.com WebMap 2.0 www.nutrace.com.br (click on “offer list” for more information) and there is so little accountability. No one is holding us accountable publicly.” And that—for roasters who are grappling with transparency—is the crux. “We’re trying to hold ourselves accountable,” Ionescu says. “In some cases it’s less about what a consumer wants than it is about our responsibility to be as clear as possible. We need to give people more than they ask for.” In Ionescu’s view, roasters have quite a bit of power to influence the kinds of questions consumers are asking about coffee, and Counter Culture wants their customers to want transparency. This flies in the face of common business logic, in which companies anticipate and respond to their customers’ desires. Counter Read the reports Just Coffee www.justcoffee.co-op/tags/transparency_project Counter Culture http://counterculturecoffee.com/sustainability Coffee Bean International www.projectdirectcoffee.com Starbucks www.starbucks.com/responsibility Transparency Contract See Transparency Contracts—Measuring your relationships in dollars and sense (Roast, Sept/Oct 2007) http://coffeeexploration.blogspot.com (search for “transparency”) Culture’s approach to transparency is to try and shape consumer 34 roast J a n u a r y | F e b r u a r y 2 0 13 35

![저기요[jeo-gi-yo] - WordPress.com](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005572742_1-676dcc06fe6d6aaa8f3ba5da35df9fe7-300x300.png)