Dowling Flexible Metals ground

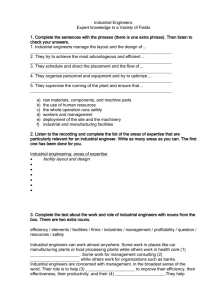

advertisement

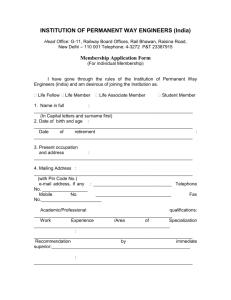

Dowling Flexible Metals ground In 1960, Bill Dowling, a "machine-tool set-up-man" for a large auto firm, became so frustrated with his job that he quit to form his own business. The manufacturing operation consisted of a few general purpose metal working machines that were set up in Dowling's garage. Space was such a constraint that it controlled the work process. For example, if the cutting press was to be used with long stock, the milling machines would have to be pushed back against the wall and remain idle. Production always increased on rain-free, summer days since the garage doors could be opened and a couple of machines moved out onto the drive. Besides Dowling, who acted as salesman, accountant, engineer, president, manufacturing representative, and working foreman, members of the original organization were Eve Sullivan, who began as a part-time secretary and payroll clerk; and Wally Denton, who left the auto firm with Bill. The workforce was composed of part-time "moonlighters," full-time machinists for other firms, who were attracted by the job autonomy which provided experience in setting up jobs and job processes, where a high \ degree of ingenuity was required. The first years were touch and go with profits being erratic. Gradually the firm began to gain a reputation for being ingenious at solving unique problems and for producing a quality product on, or before, deadlines. The "product" consisted of fabricating dies for making minor component metal parts for automobiles and a specified quantity of the parts. Having realized that the firm was too dependent on the auto industry and that sudden fluctuations in auto sales could have a drastic effect on the firm's survival, Dowling began marketing their services toward manufacturing firms not connected with the auto industry. Bids were submitted for work that involved legs for vending machines, metal trim for large appliances, clamps and latches for metal windows, and display racks for small power hand tools. As Dowling Flexible Metals became more diversified, the need for expansion forced the company to borrow building fiends from the local bank, which enabled construction of a small factory on the edge of town. As new markets and products created a need for in creasingly more versatile equipment and a larger workforce, the plant has since expanded twice until it is now three times its original size. In 1980, bowling Flexible Metals hardly resembles the garage operation of the formative years. The firm now employs approximately thirty full-time journeymen and apprentice machinists, a staff of four engineers that were hired about three years ago, and a full-time office secretary subordinate to Eve Sullivan, the Office Manager. Their rapid growth has created problems that in 1980 have not been resolved. Bill bowling, realizing his firm is suffering from growing pains, has asked you to "take a look at the operation and make recommendations as to how things could be run better." You begin the consult ing project by interviewing bowling, other key people in the firm, and workers dirt in the shop who seem willing to express their opinions about the firm. Bill Dowling, OwnerPresident "We sure have come a long way from that first set-up in my garage. On a nice day we would get everything all spread out in the drive and then it would start pouring cats and dogs-so we would have to move back inside. It was just like a one-ring circus. Now it seems like a three-ring circus. You would think that with all that talent we have here and Case 12 Dowling Flexible Metals all the experience, things would run smoother. Instead, it seems I am putting in more time than ever and accomplishing a whole lot less in a day's time. "It's not like the old days. Everything has gotten so complicated and precise in design. When you go to a customer to discuss a job you have to talk to six kids right out of engineering school. Every one of them has a calculator-they don't even carry slide rules anymore-and all they can talk is fancy formulas and how we should do our job. It just seems I spend more time with customers and less time around the shop than I used to. That's why I hired the engineering staff-to interpret specifications, solve engineering problems, and draw blueprints. It still seems all the problems are solved out on the shop floor by guys like Walt and Tom, just like always. Gene and the other engineers are necessary, but they don't seem to be working as smoothly with the guys on the floor as they should. "One of the things I would like to see us do in the future is to diversify even more. Now that we have the capability, I am starting to bid jobs that require the computerized milling machine process tape. This involves devising a work process for milling a part on a machine anal then making a computer process tape of it. We can then sell copies of the tape just like we do dies and parts. These tapes allow less skilled operators to operate complicated milling machines without the long apprenticeship of a tradesman. All they have to do is press buttons and follow the machine's instructions for changing the milling tools. Demand is increasing for the computerized process tapes. "I would like to see the firm get into things like working with combinations of bonded materials such as plastics, fiberglass, and metals. I am also starting to bid jobs involving the machining of plastics and other materials beside metals." Wally Denton, Shop Foreman, First Shift "Life just doesn't seem to be as simple as when we first started in Bill's garage. In- those days he would bring a job back and we would all gather `round and decide how we were going to set it up and who would do it. If one of the `moonlighters' was to get the job either Bill or I would lay the job out for him when he came in that afternoon. Now, the customers ideas get processed through the engineers and we, out .here in the shop, have to guess just exactly what the customer had in mind. "What some people around here don't understand is that I am a partner in this business. I've stayed out here in the shop because this is where I like it and it's where I feel most useful. When Bill isn't here, I'm always around to put out fires. Between eve, Gene, and myself we usually make the right decision. "With all this diversification and Bill spending a lot of time with customers, I think we need to get somebody else out there to share the load." Thomas McNull, Shop Foreman, Second Shift "In general, I agree with Wally that things aren't as simple as they used to be, but I think, given the amount of jobs we are handling at any one time, we run the shop pretty smoothly. When the guys bring problems to me that require major job changes, I get Wally's approval before making the changes. We haven't had any difficulty in that area. "Where we run into problems is with the engineers. They get the job when Bill brings it back. They decide how the part should be made and by what process, which in turn pretty much restricts what type of dies we have to make. Therein lies the bind. Oftentimes we run into a snag following the engineers' instructions. If it's after five o'clock, the engineers have left for the day. We, on the second, shift, either have to let the job sit until the next morning or solve the problem ourselves. This not only creates bad feelings between the shop personnel and the engineers, but it makes extra work for the engineers because they have to draw up new plans. “I often think we have the whole process backwards around here. What we should be doing is giving the job the journeymen – after all, these guy have a lot of experence 110 Part 3 Organizational Structure and Design and know-how-then give the finished product to the engineers to draw up. I'll give you an example. Last year we got a job from a vending machine manufacturer. The job consisted of fabricating five sets of dies for making those stubby little legs for vending machines, plus five hundred of the finished legs. Well, the engineers figured the job all out, drew up the plans, and sent it out to us. We made the first die to specs, but when we tried to punch out the leg on the press, the metal tore. We took the problem back to the engineers, and after the preliminary accusations of who was responsible for the screw up, they -.,changed the raw material specifications. We waited two weeks for delivery of the new steel, then tried again. The metal still tore. Finally, after two months of hassle, Charlie Oakes and I worked on the die for two days and finally came up with a solution. The problem was that the shoulders of the die were too steep for forming the leg in just one punch. We had to use two punches (see Exhibit 1). The problem was the production process, not the raw materials. We spent four months on that job and ran over our deadline. Things like that shouldn't happen." Charlie Oakes, Journeyman Apprentice , Gene Jenkins, Chief Engineer "Really, I hate to say anything against this place because it is a pretty good place to work. The pay and benefits are pretty good and because it is a small shop our hours can be some what flexible. If you have a doctor's appointment you can either come in late or stay until you get your time in or punch out and come back. You can work as much overtime as you want to. "The thing I'm kind of disappointed about is that I thought the work would be more challenging. I'm just an apprentice, but I've only got a year to go in my program before I can get my journeyman's card, and I think I should be handling more jobs on my own. That's why I came to work here. My Dad was one of the original `moonlighters' here. He told me about how interesting it was when he was here. I guess I just expected the same thing." "I imagine the guys out in the shop already have told you about `The Great Vending Machine Fiasco.' They'll never let us forget that. However, it does point out the need for better coordination around here. The engineers were hired as engineers, not as draftsmen, which is just about all we do. I'm not saying we should have the final say on how the job is designed, because there is a lot of practical experience out in that shop; but just as we haven't their expertise neither do they have ours. There is a need for both, the technical skill of the engineers and the practical experience of the shop. "One thing that would really help is more information from Bill. I realize Bill is spread pretty thin but there are a lot of times he comes back with a job, briefs us, and we Case 12 Dowling Flexible Metals still have to call the customer about details because Bill hasn't been specific enough or asked the right questions of the customer. Engineers communicate best with other engineers. Having an engineering function gives us a competitive advantage over our competition. In my opinion, operating as we do now, we are not maximizing that advantage. "When the plans leave here we have no idea what happens to those plans once they are out in the shop. The next thing we know, we get a die or set of dies back that doesn't even resemble the plans we sent out in the shop. We then have to draw up new plans to fit the dies. Believe me, it is not only discouraging, but it really makes you wonder what your job is around here. It's embarrassing when a customer calls to check on the status of a job and I have to run out in the shop, look up the guy handling the jolt, and get his best estimate of how the job is going." Eve Sullivan, Office Manager "One thing is for sure, life is far from dull around here. It seems Bill is either dragging in a bunch of plans or racing off with the truck to deliver a job to a customer. "Really, Wally and I make all the day-to-day decisions around here. Of course, I don't get involved in technical matters. Wally and Gene take care of those, but if we are short handed or need a new machine, Wally and I start the ball rolling by getting together the necessary information and talking to Bill the first chance we get. I guess you could say that we run things around here by consensus most of the time. If I get a call from a customer asking about the status of a job, I refer the call to Gene because Wally is usually out in the shop. "I started with Bill and Wally twenty years ago, on a part-time basis, and somehow the excitement has turned into work. Joan, the office secretary, and I handle all correspondence, bookkeeping, payroll, insurance forms, and everything else besides run the office. It's just getting to be too hectic-I just wish the job was more fun, the way it used to be. Having listened to all concerned, you returned to Bill's office only to find him gone. You tell Eve and Wally that you will return within one week with your recommendations.