who carries the can?

advertisement

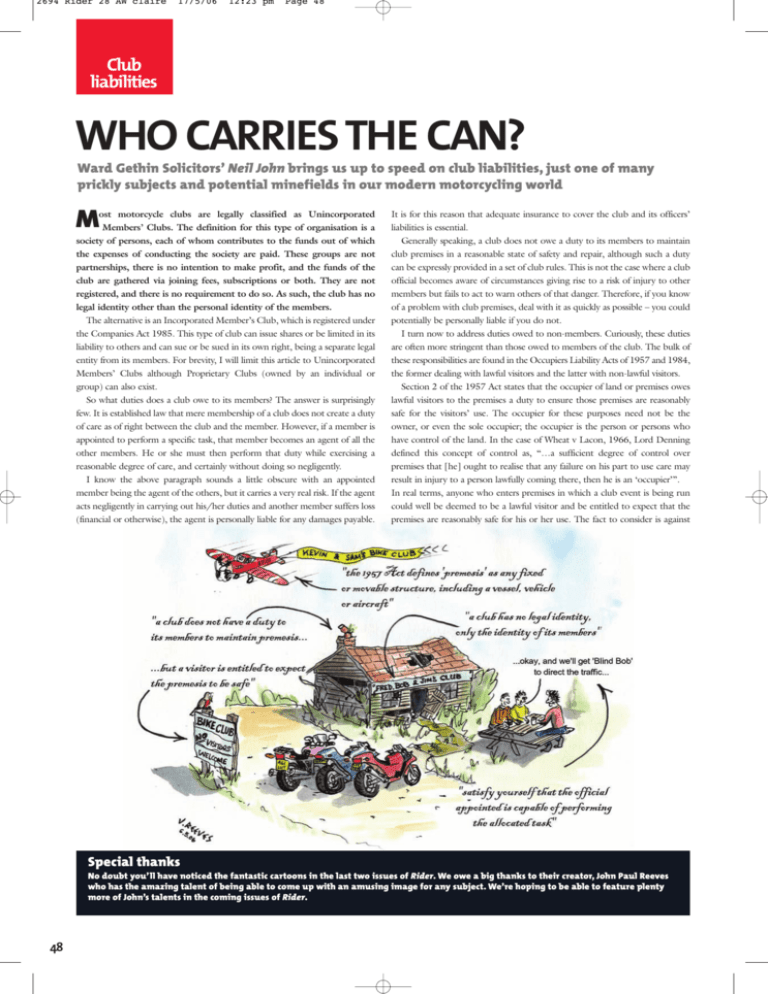

2694 Rider 28 AW claire 17/5/06 12:23 pm Page 48 Club liabilities WHO CARRIES THE CAN? Ward Gethin Solicitors’ Neil John brings us up to speed on club liabilities, just one of many prickly subjects and potential minefields in our modern motorcycling world M ost motorcycle clubs are legally classified as Unincorporated Members’ Clubs. The definition for this type of organisation is a society of persons, each of whom contributes to the funds out of which the expenses of conducting the society are paid. These groups are not partnerships, there is no intention to make profit, and the funds of the club are gathered via joining fees, subscriptions or both. They are not registered, and there is no requirement to do so. As such, the club has no legal identity other than the personal identity of the members. The alternative is an Incorporated Member’s Club, which is registered under the Companies Act 1985. This type of club can issue shares or be limited in its liability to others and can sue or be sued in its own right, being a separate legal entity from its members. For brevity, I will limit this article to Unincorporated Members’ Clubs although Proprietary Clubs (owned by an individual or group) can also exist. So what duties does a club owe to its members? The answer is surprisingly few. It is established law that mere membership of a club does not create a duty of care as of right between the club and the member. However, if a member is appointed to perform a specific task, that member becomes an agent of all the other members. He or she must then perform that duty while exercising a reasonable degree of care, and certainly without doing so negligently. I know the above paragraph sounds a little obscure with an appointed member being the agent of the others, but it carries a very real risk. If the agent acts negligently in carrying out his/her duties and another member suffers loss (financial or otherwise), the agent is personally liable for any damages payable. It is for this reason that adequate insurance to cover the club and its officers’ liabilities is essential. Generally speaking, a club does not owe a duty to its members to maintain club premises in a reasonable state of safety and repair, although such a duty can be expressly provided in a set of club rules. This is not the case where a club official becomes aware of circumstances giving rise to a risk of injury to other members but fails to act to warn others of that danger. Therefore, if you know of a problem with club premises, deal with it as quickly as possible – you could potentially be personally liable if you do not. I turn now to address duties owed to non-members. Curiously, these duties are often more stringent than those owed to members of the club. The bulk of these responsibilities are found in the Occupiers Liability Acts of 1957 and 1984, the former dealing with lawful visitors and the latter with non-lawful visitors. Section 2 of the 1957 Act states that the occupier of land or premises owes lawful visitors to the premises a duty to ensure those premises are reasonably safe for the visitors’ use. The occupier for these purposes need not be the owner, or even the sole occupier; the occupier is the person or persons who have control of the land. In the case of Wheat v Lacon, 1966, Lord Denning defined this concept of control as, “…a sufficient degree of control over premises that [he] ought to realise that any failure on his part to use care may result in injury to a person lawfully coming there, then he is an ‘occupier’”. In real terms, anyone who enters premises in which a club event is being run could well be deemed to be a lawful visitor and be entitled to expect that the premises are reasonably safe for his or her use. The fact to consider is against Special thanks No doubt you’ll have noticed the fantastic cartoons in the last two issues of Rider. We owe a big thanks to their creator, John Paul Reeves who has the amazing talent of being able to come up with an amusing image for any subject. We’re hoping to be able to feature plenty more of John’s talents in the coming issues of Rider. 48 2694 Rider 28 AW 17/5/06 2:56 pm Page 49 It is wise to check carefully any premises/ equipment hired or leased for club events before allowing visitors access whom or what that right is enforceable. It may seem that the obligations under the 1957 Act are all encompassing, but this is not true. The occupier is only liable for defects in the condition of the premises or things which are already on or part of it. Anything brought onto the land by visitors, or activities carried out by them, are generally not the responsibility of the occupier unless they are specifically organised by the occupier. The 1957 Act defines premises as any fixed or moveable structure, including a vessel, vehicle or aircraft. The courts have also considered the definition of premises. In the case of Wheeler v Copas, 1981, a defective ladder was deemed to be within definition of premises, as was a tunnel-cutting machine in Bunker v Charles Brand & Sons Ltd, 1969. But what of non-lawful visitors – people who simply shouldn’t be there? Historically, these ‘visitors’ (invariably trespassers or possibly burglars) were considered to be at their own risk when entering premises in such a way. Indeed, the Court in Addie v Dumbreck, 1929, held that no duty was owed by the occupier other than to refrain from inflicting damage intentionally or recklessly on a trespasser known to be present on the land. This somewhat cursory stance was changed in 1972 in the case of British Railways Board v Herrington. The court made it clear that an occupier’s duty to a non-lawful visitor is not as high as that owed to a lawful visitor. This new obligation was referred to as a duty of common humanity. It was felt that to impose similar obligations as those owed to lawful visitors would infringe the occupier’s rights as the trespasser had forced him (her) self into a relationship of close proximity to the occupier. The case of Herrington established a duty of common humanity, namely that when a reasonable man, knowing the facts which the occupier knew would appreciate a trespasser’s presence at the point and time of danger was so likely that in all the circumstances, it would be inhumane not to give an effective warning of the danger. This duty is not a fixed test and varies according to the occupier’s knowledge, abilities and resources. Each case of this kind will therefore turn on its facts. The decision in Herrington was replaced in 1984 by the statutory provisions contained in Section 1(3) of the Occupiers Liability Act 1984. The formal test is now: An occupier owes a duty of care to a non-lawful visitor if: a) he is aware of the danger or has reasonable grounds to believe it exists b) he knows, or has reasonable grounds to believe that the non-visitor is in the vicinity of the danger concerned or that he may come into the vicinity of the danger (in either case, whether the non-visitor has lawful authority to be there or not); and c) the risk is one against which, in all the circumstances, he may reasonably be expected to offer the non-visitor some protection. In essence, an occupier owes only a duty to ensure his/her premises contain no obvious dangers or protects non-lawful visitors from any dangers he/she knows or believes to exist. You will note liberal use of the word reasonable, which indicates the courts take a subjective view of every case and will decide each one on its own merits rather than taking a broad brush approach. While an error of finding of law on the part of the court is appealable, an error of finding of fact generally is not. One thing which has not been covered so far is the concept of bailment. Bailment occurs when one party hands property to another party for safekeeping. There is an obligation on the bailee (recipient) to return the item in the condition in which it was passed to him. The classic example of the application of this concept is a helmet park at a bike show. If you are organising such an event, it may be prudent to have a condition slip for each helmet taken in, where any imperfections or damage already on the helmet are noted at the time it is accepted. The owner’s signature on such a document at the time of deposit may well prevent arguments later. So what are we to learn from this foray into the murky world of club liabilities? The first thing to ensure is that your club has adequate public liability insurance which covers not only claims for defective premises, but also indemnifies club officials who commit negligent acts in the proper execution of their duties on behalf of the club, and to ensure there is enough cover in financial terms to pay for any damage that may be claimed for. For example, if the limit of cover for personal items is say £250 per claimant, the club is likely to be underinsured if a digital camera or camcorder is destroyed at a club event. Secondly, it is wise to check carefully any premises hired or leased for club events before allowing visitors access. While insurance cover may well be in place, too many claims upon it will raise the future premiums and may even render the club uninsurable if the underwriters view the club activities as too much of a risk to cover. Thirdly, when entrusting tasks to club officials, it is wise to satisfy yourself that the official in question is capable of performing the allocated task. Once you have covered your risks correctly, and good insurance planning is as important as planning the event itself, the only thing left to do is enjoy your club event. This is not designed to be an exhaustive guide and if you are in any doubt, please seek expert advice before you run the event. For questions about the insurance cover provided to clubs as part of the affiliation to the BMF, contact our membership secretary Rachel Crossley on 0116 284 5380 or email membership@bmf.co.uk For straightforward advice contact the BMF Biker Legal Line on 0800 856243. Motorcycle Rider 49