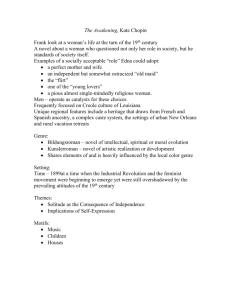

Fairy Tales, Folk Tales, and Intertextuality

advertisement