The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Entrepreneurial Status: A

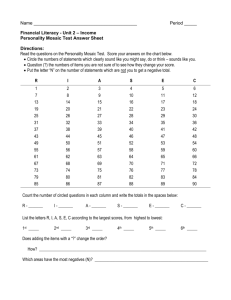

advertisement