northumberland house - 8 Northumberland Avenue

advertisement

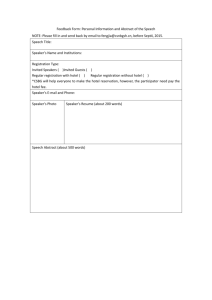

A Short History of Northumberland House 8 Northumberland Avenue London WC2N 5BY London Northumberland House - Canaletto - 1752 A Short History The Northumberland, Northumberland Avenue, was built as a 500-room ‘grand hotel’ between 1882 and 1887. Northumberland Avenue was created in 1875-6, a major element in the Metropolitan Board of Works’ civic improvements to the West End, though it involved the demolition of the original Northumberland House, the celebrated Jacobean mansion. The Northumberland Avenue Hotel Company, set up in 1882 to develop the site, appointed Florence & Isaacs as architects and started work on the building. However, costs soared because of difficult ground conditions, and the company went bankrupt in 1884. It was taken over by the vast financial empire of Jabez Balfour; the hotel was completed, and opened and launched as the Hotel Victoria in 1887. Shortly after, it was caught up in the collapse of Balfour’s empire, and was purchased by the rival Gordon Hotels group. It traded as a hotel, with a brief interval during the Great War, until 1940, when it was requisitioned by the War Office. It has been occupied by the Crown ever since. The building is listed at grade II, and is in the Trafalgar Square Conservation Area. The site Northumberland Avenue was laid out on the site of Northumberland House between 1875 and 1876. The old Northumberland House had been one of the most celebrated aristocratic residences in London, designed by Bernard Jansen and Gerard Christmas and dating from c1600. The house was remodelled several times, and was given superb new state-rooms by Robert Adam in the 1770’s. By the 1870’s it was the last survivor of the great aristocratic mansions which had lined the north bank of the Thames since the sixteenth century. It fell victim to the Metropolitan Board of Works’ determination to improve Westminster’s traffic circulation by providing a link 2 between Trafalgar Square and the new Embankment. The house was compulsorily purchased and, after much protest, demolished in 1874. The new street was designed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette and George Vulliamy, respectively engineer and architect to the Metropolitan Board of Works. It was built by Mowlem and Company, who began work in the summer of 1875, and finished in time for it to be opened in March1876, for a contract price of £15,750, not including the wood-block paving of the roadway. It was designed as an avenue planted with trees. A subway for gas and water pipes, seven feet high, ran its whole length. Description of the Building Façade The carefully controlled ornament is generally Italian and cinquecento in manner though the scale and the mansard roofline owe more to the Second Empire Paris, a manner popular for large hotels. It is faced in high quality Portland stone ashlar. The high arched entrance has a fine coffered ceiling of faience tiles. The sculptural decoration was illustrated in the Builder on 6 November 1886, with figures of Day and Night carved by J Boekbinder. Soon after completion of the hotel, an elaborate glass and iron canopy was built spanning the pavement in front of the main entrance, made by Coalbrookdale Company. Florence & Isaacs application for this was approved by the Metropolitan Board of Works on 29 July 1887, and it appears in several early photographs of the hotel. The stone carving on the upper floors was by Daymond & Son. The ornamental iron balconies on the front, were by Starkie Gardner & Co. 3 The Marble Hall and Coffee Room The walls are lined with alabaster, with bands of reddish Bardiglio marble, also used for the door surrounds. The dado has a cap and base of Verde de Prato marble, with a die (panel) of Sanguino; a similar combination was used for the columns. The vestibule was also paved in marble. This area survives much as built in 1883-1886. This area was originally occupied by an impressive staircase on the ‘imperial’ plan, with a single flight 13 feet wide to a half-landing, and two return flights. This sat within a double-height marble-lined hall. It only ever gave access to the first floor, and it was evidently considered that it took up a disproportionate amount of space, and the space laid out as a lounge, with two fireplaces on either side. A wide opening was created to link the newly-created Coffee Room (now Boyds). When the staircase was removed in 1914, the coffee room was linked to the Marble Hall. The Coffee Room retains its 1880s ceiling with its bracketed cornice. The marble wall treatment, matching the adjacent hall, the ceiling plasterwork was replaced in a simplified neoclassical style. The Ballroom This magnificent room, the highlight of the hotel’s interior, is one of the grandest Victorian hotel interiors remaining in London. On the original plan it is labelled ‘Salle a Manger’. It was built with four-bay aisles to either side, and an apse at the far end. The rich ornament, in an Italian cinquecento style, was, like the main entrance carving, by Boekbinder, and largely survives. In the spandrels over the arches are reclining figures representing the arts and sciences. The great Corinthian semicolumns have rich leaf-decoration around the foot of their shafts. In the four big windows on the south side of the room the splendid original painted glass remains. There is elaborate renaissance ornament, and figures representing sculpture, painting, music and poetry. Early photographs show that the five windows in the apse also had painted or stained glass, with heraldic decoration The room originally had walnut panelling to eight feet in height, some of which survives at its north-east end. The upper parts of the walls had bevelled mirrors and tapestries: In 1924 the hotel made application for the installation of a gallery, within the north arcade of the room. The gallery itself was intended for musicians, while the newly enclosed space below was to be a serving area. The Reception Room and Salon This original three-bay room retains its original joinery, and its splendid plaster ceiling in a rich rococo manner. In 1923 it was called the Mayflower Room now called the Salon which retains its original joinery, and a magnificent ceiling 4 The London hotel trade The coming of the railways was the key factor in the development of the modern hotel from the eighteenth-century coaching inn. Euston Station developed the twin Victoria and Adelaide hotels (1846); followed by the Great Northern Hotel at King’s Cross by Lewis Cubitt (opened 1854). A new scale was announced by P C Hardwick’s Great Western Hotel (1854), James Knowles’ Grosvenor Hotel at Victoria Station (1860), and George Gilbert Scott’s Midland Grand at St Pancras (1868-72). The idea of a hotel as a grand building of a public character became established. The hotel trade was itself expanding and developing, with entrepreneurs moving into areas of business hitherto supplied by a vast assortment of coffee houses, clubs, dining rooms, private rooms and taverns. A key figure in this development was Frederick Gordon (1835-1904). His father ran a number of the ‘principal dining rooms’ (restaurants) that were springing up to cater for the business classes and day visitors. In 1874 he opened the Holborn Restaurant. In 1877, though without previous experience of the hotel trade, Gordon began work on the Grand Hotel, Northumberland Avenue, opposite the site of Northumberland House, opening in 1881. Its huge and immediate success enabled Gordon to found the First Avenue Hotel, Holborn (1883), and then the Hotel Metropole, Northumberland Avenue (1885). The Gordon Hotel Group was the undoubted pace-setter and leader for the hectic development in ‘grand hotels’ which lasted through the 1880’s and 1890’s. 5 The Northumberland Avenue Hotel Company The Northumberland Avenue Hotel Company was set up in the summer of 1882, apparently copying Gordon’s formula. A board was set up under the chairmanship of Viscount Pollington, and a prospectus issued, predicting that a 500-bedroom hotel could be built for £200,000m and that dividends of nineteen-and-a-half per cent were to be expected. Florence & Isaacs were appointed as architects; they had designed the Holborn Viaduct Hotel (1876), and were to design the Coburg Hotel in 1896 (now the Connaught). Progress was swift, and in October 1882, Perry & Co of Tredegar Works, Bow entered into a contract for the construction (Builder, 14 October 1882, p492). The Building News illustrated the design for the façade on 2 March 1883. The foundation stone of the new hotel was laid in July 1883. The Building News reported on 28 July that: The building has a frontage of 354ft and a depth of about 162ft, and occupies a triangular site. On the ground floor are dining hall, 100ft by 42ft, a restaurant, the frontage being occupied by private dining rooms and large entrance hall leading to central staircase. In the basement are a range of bathing rooms in front, swimming bath, cellars and engine room. The style of Renaissance, of somewhat severe character. It seems to have taken the Northumberland Avenue Hotel Company a long time to start work, though it is not clear whether this was due to difficulties in negotiating with the Metropolitan Board of Works (the freeholders of the site) or in raising money. They did not finalise the agreement to lease the site until 8 August 1884 (Metropolitan Board of Works minutes). Agreement was reached over the design on 11 August; copies of the approved elevation and plan survive in the Metropolitan Record Centre, signed by George Vulliamy, Chief Architect to MBW (LCC/VA/DD/159/1). This design shows a design very similar to the hotel as built, but 55 feet longer, having eight bays between the centre pavilion and the end pavilions. The reduction in the size of the building was caused by the collapse of the company. When the site was opened up, it was soon found that the ground conditions were very difficult. The contractors had to go down fifty feet to find a solid foundation for 6 the main walls, and hit an underground rivulet running from Highgate down to the Thames. A 10hp engine had to pump the water days and night for seven months, until a six-foot concrete bed was laid over the entire site (Builder, 1 May 1886, p639). This vast increase in the cost forced the Company into bankruptcy late in 1884 by which time the shares, floated at £9, had fallen to £2.17s 6d. Part of the site was sold to help cover the debts, reducing the length of the façade. The hotel was bought by the ‘Building Securities Company’, part of the octopoidal group of companies controlled by Jabez Balfour, and the contractor JW Hobbs & Co of Croydon, another part of Balfour’s empire, took over the construction work, completing it in 1886. Jabez Balfour and the Liberator Building Society Spencer Jabez Balfour was born in 1843, son of James Balfour, a marine store dealer. His mother, Clara Lucas Balfour, was a fervent evangelical and propagandist for teetotalism, and Balfour was brought in an atmosphere of strict Baptist evangelism. The family were poor, but were well known in nonconformist and temperance circles. Balfour worked for a firm of parliamentary agents, and then became a partner in another such firm. In 1867, he and other nonconformists joined together to form a building society for small investors and borrowers, the Lands Allotment Company, founded with capital of £50,000. At its foundation, it was similar to the legion of cooperative and mutual association then being founded all over Britain. Its members were mostly Nonconformists, and its agenda was to help its members become property owners, and escape from the clutches of landlords. Balfour swiftly attracted an army of nonconformists’ depositors and investors, in part by soliciting the support of their ministers. The Lands Allotment Company was the starting point for a huge financial empire. The Liberator Building Society was added in 1868, the House and Land Investment Trust in 1875, the London and General Bank in 1882, and the Building Securities Company in 1884, with capital of £500,000. This last seems to have been set up to acquire and complete the Northumberland Avenue Hotel. Balfour had formed an association with a Croydon builder, J W Hobbs, and arranged for him to receive vast building contracts. In 1885, a new company, Hobbs & Company, was set up as a general contractor, with a capital of £250,000. This company completed the Northumberland Avenue Hotel, or Hotel Victoria, 1884-6. Over these years, Balfour and Hobbs embarked on some of the most ambitious building developments London had ever seen, including Whitehall Court and the National Liberal Club (by Archer & Green, c1884-92), the Hyde Park Hotel (Archer & Green, 1888), the Hotel Cecil, Strand (Perry & Reed, 1888-95), and the Albert Hall (1889). The hotel was thus one of the several immense developments being carried on simultaneously by Balfour’s group of companies. In fact, this imposing – looking empire was a morass of corruption and ineptitude, though it remains hard to say how far its downfall was caused by one or the other. Balfour attracted thousands of depositors and investors to his companies by offering a markedly higher rate of interest (around eight per cent) on accounts. He seems to have found early on, that he could never make the profits to support these rates from mortgage business, and began to speculate in property, ever more wildly. He raised capital by setting up new companies, inviting new subscriptions for shares, and using these proceeds to pay the existing depositors’ interest. 7 Balfour claimed in 1885 that all of his companies were ‘entirely and absolutely independent of the others and not in any dependent on them’. This was the reverse of the truth. In fact, the vast sums deposits by thousands of individuals with the Liberator Building Society had mostly been lent to other Balfour companies, and much of it sunk into his and Hobbs’ huge developments, including the Northumberland Avenue Hotel. On the strength of all this, Balfour became Liberal MP for Tamworth in 1880, Mayor of Croydon in 1883 and MP for Burnley in 1889. In 1893 the roof fell in, as creditors began to foreclose on his companies. Hobbs and Wright (the groups’ solicitor) were arrested for fraud, and Balfour himself fled to Argentina. The Liberator Building Society’s principal assets were found to be £3,251,218 of debts owed to it by three other Balfour companies, all of them insolvent. Thousands of depositors lost almost everything, and several suicides were reported as having been caused by the crash. The story ran for months. Balfour was found and extradited to stand trial in 1895, was convicted of fraud on a technicality (over a mere, £20,000), and was sentenced to 14 years imprisonment. Released in 1906, he mended his own fortunes with a series of newspaper articles about his imprisonment (published as ‘My Prison Life’, 1907). He died on a Great Western railway train in February 1916. He had caused one of the greatest financial scandals of the Victorian age. The Hotel Victoria On Balfour’s takeover of the hotel, Florence & Isaacs were retained as architects. Their original design was for a hotel 353ft long. 53 feet of this site (the present Nigeria House) had been sold, and Florence & Isaacs reduced the building accordingly; their original design had eight window-bays on either side, between the centre and end pavilions, the hotel as built has only six bays. A revised elevation was received by the Metropolitan Board of Works on 14 March 1885 (Metropolitan Record Centre, LCC/VA/DD/159/1). The huge building received considerable attention in the building press, with long articles on in the Builder on 1 May 1886, when it was nearing completion, and on 14 May 1887, when it had recently been opened; these provide a good deal of information about its construction. The hotel was built to a very high standard. The whole façade was faced with ashlar masonry of Portland Stone, with fine carved decoration by Boekbinder. The construction was designed to be largely fireproof, with cast-iron stanchions and wrought-iron girders used throughout. The floors are all of concrete, made of coke breeze and Portland cement in a proportion of 4 to 1; the internal lintels are of a similar material. The hotel was fitted out with the newest technology. Electric light was fitted through, but ‘to guard against the possibility of mishap’, was generally duplicated with gaslight. There were also electric bells with signal semaphores and speaking tubes, and two passenger lifts and two goods lifts. Steam power, used for cooking, heating and dynamos for the electric light, was generated by two Lancashire boilers, each thirty feet long. With five hundred rooms (and four bathrooms) it was big, though smaller than the neighbouring Metropole with nearly six hundred rooms, finished in 1885. The hotel was evidently near completion when the Builder described it on 1 May 1886, and was fitted out and furnished during that year. It was opened early in 1887, and was named the Hotel Victoria, presumably in honour of the Queen’s Golden Jubilee. 8 The hotel swiftly built up a lucrative banqueting trade, with dinner contracts for the 9th Norfolk Regiment, the Buffs, the Grand Masters’ Chapter, and the Institute of Civil Engineers. £1500 a year was obtained from the sale of showcase space to 32 companies including Liberty, Cadbury’s and the UK Tea Company. Within a few years of its completion, the hotel was dragged into the chaos caused by the collapse of Balfour’s empire in 1893. The Hotel Victoria was at least a going concern, unlike many of Balfour’s businesses, and the liquidator sold it for £417, 433 to Frederick Gordon, owner of the neighbouring Metropole and Grand Hotel. In 1893, a new illustrated prospectus of ‘The Hotel Victoria’ was published. In 1911, Gordon Hotels began planning a major refurbishment of the hotel, calling in the architect William Campbell-Jones to discuss the removal of the grand staircase, and the conversion of the space into a new lounge. Work did not begin until early in 1914, and on 4 March Campbell-Jones submitted drawings of the alterations to the LCC; one dated 25 March 1914 survives in the Metropolitan Record Office (Theatre Cases Index). A large opening was created at the back of the staircase hall, with steel stanchions and a steel girder, linking the newly formed space to the Coffee Room. The original walnut panelling of the Coffee Room was removed and replaced with banded marble panelling, to match that of the former staircase hall; indeed the decoration of both spaces seems to have been simplified to satisfy the somewhat severer taste of the age. In April 1914, Campbell-Jones notified the LCC that ‘in addition to enlarging the Coffee Room, it is proposed to provide a screen and revolving doors in the main entrance, and a new staircase in the basement…’, the latter being the first indication of the major works at basement level which followed. The huge Billiard Room in the basement also seems to have been found dispensable, and around this time the decision was taken to convert it into a new ballroom or banqueting hall. Wok was evidently interrupted by the Great War. In 1916 the hotel closed its Grill Room, which was let to Messrs Cox’s Bank, and in 1917 the hotel seems to have been taken over by the War Office. On the company’s recovering the hotel in 1919, they resumed work on alterations to the basement. In the event, CampbellJones did not get the job, which was given to the well-known firm of furnishers and decorators, Maple & Company. On 1 July 1919 they submitted plans to the LCC for alterations ‘in connection with proposed new entrance from Northumberland Avenue, extension in the Basement for Banquet Room, Toilet Rooms & c….’. The work fell foul of the fire brigade, who demanded additional emergency exits. On 16 October 1919, E C Macpherson or Maple & Company wrote with a revised plan, showing an additional exit created from the west side of the new Banqueting Hall, via a new staircase to ground floor level coming out near the Smoking Room. This was not the end of the scheme’s difficulties, for in December 1919 the LCC refused to approve the ventilation arrangements. Campbell-Jones seems to have been brought back to iron out the details, submitting new drawings for the ventilation arrangement in January 1920. The completed suite of rooms, with their new entrance from the street, was decorated by Maple & Company in a smart eighteenth-century French manner, and named in honour of King Edward VII. Partial plans for these alterations survive in the Metropolitan Record Centre (Theatre Cases Index, GLC/AR/BR/19/0171), and the work is documented in the case file, GLC/AR/BR/07/0171. In 1923, the hotel recovered its Grill Room from Cox’s Bank, and re-opened it as a Smoking Room and overflow banqueting room. Further work was done to modernise the hotel in 1923, with more bathrooms being installed, and hand-basins put in every 9 bedroom (Westminster Archives, Drainage Plans). The hotel continued to trade up until 1940, the last year when it appears in the directories. In 1935, a further attempt was made to modernise the main Dining Hall or Salle a Manger with an Art Deco redecoration. This was the last major adaptation to be carried out by Gordon Hotels. In 1940 the Hotel Victoria ceased trading, and was requisitioned by the War Office. It has been in official occupation ever since. Florence and Isaacs Lewis Henry Isaacs (c1830 – 1908) and Henry Louis Florence (c1843 – 1916) were a fairly typical successful late Victorian commercial architectural partnership. Isaacs, the senior of the partnership, was from Lancaster, where he had been articled to Edmund Woodthorpe. Coming to London, he worked as a surveyor in Holborn, and published practical treatises on paving, sewerage and artisan housing. He was a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers and a fellow of the Surveyors’ Institution, as well as a Fellow of the RIBA. Henry Florence came from Streatham, and had a promising early career, articled to EC Robbins, JR Hakewill and F Pepys Cockerell, and studying at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. He was Soane Medallist of the RA in 1869 and an Associate of the RIBA in 1869. He seems to have entered Isaac’s practice around 1876, and until they formed a successful partnership. Both of them seem to have been public-spirited men, Isaacs serving as Master of the Paviour’s Company in 1903, while Florence was Master of the Haberdashers in 1914. Isaacs was briefly MP for Walworth, Alderman and (1902-4) Mayor of Kensington, while Florence was President of the Architectural Association. Isaacs seems to have had business acumen, serving as a director and later Chairman of the Metropolitan District Railway. The practice specialised in hotels, grand in scale and eclectic in style, but their oeuvre has suffered heavy losses. The Holborn Viaduct Hotel, High Holborn (1876) has been demolished, as have the Carlton Hotel, Pall Mall (1897-9) and the First Avenue Hotel, Holborn (1900), and Cadby’s Piano Manufactory, Hammersmith (later the headquarters of J.Lyons & Company, c1874). In London, the King Lud on Ludgate Circus (1870, in a commercial Italianate style) survives, as does the Connaught (formerly Coburg) Hotel, Mount Street, Mayfair (1901), its exterior in a simple Norman Shaw Queen Anne style, but its interior retaining ‘much of the original late-Victorian richness and amplitude’, as the Survey of London puts it. Northumberland House is probably their most important surviving work. 10